Author Nadia Bolz-Weber questions the impact that the purity culture has had on sexuality. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

(RNS) — Nadia Bolz-Weber, a Lutheran minister and best-selling author, has been collecting purity rings — made popular in 1990s-era programs such as “True Love Waits” — for a protest project inspired in part by the biblical prophet Isaiah.

The project is a provocative bit of marketing for “Shameless: A Sexual Reformation,” the forthcoming book from Bolz-Weber, founder and former pastor of House For All Sinners and Saints, a Lutheran congregation in Denver.

It’s also a serious commentary on the legacy of the “purity movement” of the 1990s and early 2000s in the era of #MeToo, #ChurchToo and #TimesUp.

That culture, said Bolz-Weber, left people with “frayed wires” when it came to sexuality and desire. It suggested, she said, that in order to please God, “you need to make sure you’re not even thinking sexual thoughts.”

Such teachings, whether explicit or implicit, were the hallmark of Christian-themed sexual abstinence programs that were common in evangelical youth culture 20 years ago. But they contradict other biblical claims, said Bolz-Weber, such as the idea that sexuality is a gift from God.

“What the church teaches is like a passive-aggressive test of our willpower, like God is saying, ‘You’re going to be designed this way but if you love me you’ll ignore it, right?’” she said. “It’s pernicious, the lies we tell kids in God’s name because of our own hang-ups.”

Bolz-Weber’s is the latest addition to a growing chorus of voices rethinking the purity movement and its lasting spiritual and psychological effects on a generation of believers.

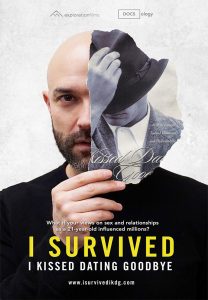

A poster for “I Survived I Kissed Dating Goodbye.” Image courtesy of isurvivedikdg.com

Among them is Joshua Harris, author of “I Kissed Dating Goodbye: A New Attitude Toward Romance and Relationships,” the 1997 book that became the de facto bible of the purity movement. Last month, Harris apologized for the harm the book had caused and asked his publisher to cease printing it.

Now 43, Harris wrote the book when he was 21 and it was published a year before he got married. The book has sold more than 1.2 million copies to date.

Harris’ disavowal of his own best-seller is chronicled in the documentary film “I Survived I Kissed Dating Goodbye,” released in late November. In it, the author has face-to-face conversations, many of them difficult, with his critics.

One of the most powerful exchanges in the film is a conversation with Elizabeth Esther, a Christian writer who’d been critical of the book on social media. She said it had been used against her “like a weapon” when she was a teenager.

“I remember feeling like an abject failure because (my husband) and I were kissing while we were engaged,” Esther said.

“And that’s a standard that’s totally not in the Bible,” Harris replies.

Whether intentional or not, in some evangelical and fundamentalist circles, Harris’ book was treated like holy writ. He wasn’t the only one writing about or espousing such extreme teachings about chastity, abstinence and “purity,” but because of the book’s success, he became the ersatz poster child for a movement.

At the end of the documentary, Harris delivers an emotional apology: “I want to say to anyone who was hurt by my book that I’m so sorry and I know that is coming too late, I know it doesn’t really change anything for you, but I never meant to harm you. And I hope that … owning up to mistakes in my book will somehow help you on your journey.”

At the height of the purity movement in the 1990s, Jeff Tacklind was a youth pastor at a large evangelical Christian church in Southern California.

While his church didn’t explicitly teach a purity curriculum, many of his young charges — especially the girls — sported promise rings.

“We were obsessed with commitments —if we could get people to commit to it, to raise a hand, to come forward, to do something, that counts — if you do it in a really compelling way, you can get people to commit to something they don’t believe. And except for the fact that surprise, surprise, it doesn’t last,” said Tacklind, now senior pastor of Little Church by the Sea, an Evangelical Free congregation in Laguna Beach, Calif.

That led to a spiritually vicious cycle of commitment-making, commitment-breaking, shame and regret, and re-committing, he said.

“Abstinence or virginity or purity, these kinds of concepts in the end just go away. The commitment lasts for a set amount of time — it doesn’t endure,” he said. “This idea of waiting until marriage, I think it was a complete failure.”

Linda Kay Klein. Courtesy photo by Jami Saunders

Linda Kay Klein, author of the new memoir “Pure: Inside the Evangelical Movement That Shamed a Generation of Young Women and How I Broke Free,” came of age inside the purity movement and has studied its ongoing impact on culture.

The church, she said, needs to be better about making amends for the damage done by the movement.

“There’s a difference between ‘we’re doing something new now’ and making amends — healing what we are in part responsible for having created in the first place, a church with generations of people living in sexual shame, and fear, and anxiety,” Klein said.

Klein found a few hopeful examples, including an evangelical congregation, Highlands Church, in Denver that hosted a six-part sermon series on sex and sexuality that focused on healing.

That series offered worshippers an opportunity to “deconstruct the unhealthy things that they learned in various places, including the church, about sex and sexuality and to reconstruct it in a healthy way,” Klein said.

When it comes to human sexuality, Klein encourages churches to confess sins of commission and omission.

“Confess commission: teaching sexual shame, though I think many didn’t intend to,” she said. “And some need to confess the sin of omission, the fact that they haven’t been talking about sex and sexuality; that we have left so many people to be taught by society and society doesn’t have very healthy sexual teachings, either.”

Tacklind, who has three adolescent children (including two daughters), doesn’t see many traces of the purity movement among church youth today.

But he wonders about its lingering negative effects on his ’90s-era youth group — one teenage girl in particular.

The girl, who today would be well into her 30s, had signed an abstinence commitment, Tacklind explained. Her father gave her a silver promise ring, which she proudly never took off. And then one day she came to her youth pastor to confide that she had been raped.

“She held up her hand and said, ‘Look at what a hypocrite I am!’ It was heartbreaking. She was a complete victim. We’d set it up to be so confusing: What do you do? What happens if you take it off?” Tacklind recalled. “All the shame and the judgment — that’s what I think of when I think of purity rings.”