People protest during a rally about the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to uphold President Donald Trump‚Äôs ban on travel from several mostly Muslim countries, Tuesday, June 26, 2018, in New York. Muslim individuals and groups, as well as other religious and civil rights organizations, expressed outrage and disappointment at the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision Tuesday to uphold President Donald Trump’s ban on travel from several mostly Muslim countries. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

(RNS) — Every morning when Khadra Abdo wakes up, her mind turns to her children.

“My first thought is that I hope they are safe today, and that stays on my mind throughout the whole day,” Abdo told Religion News Service through an interpreter provided by Church World Service.

Khadra Abdo. Courtesy photo

The 40-year-old Muslim mother of seven was separated from her five oldest children from a first marriage nearly 12 years ago when she and her second husband fled civil war twice — first in Somalia, then in Libya. When they arrived in Columbus, Ohio, as asylum seekers in 2012, she filed a request for her four teenaged daughters and one son, living with her 75-year-old mother in Ethiopia, to join her through World Relief.

Seven years later, she is still waiting. And the World Relief office that once helped her has been closed.

That closure in 2017 was a “direct result” of President Trump’s executive order to cut the number of refugees resettled that year in the United States, World Relief said at the time.

Over the past two years, the nation’s refugee resettlement system has been slowly dismantled. The process started after President Trump temporarily suspended the entire refugee program in the United States and issued the first version of a ban on travel from predominantly Muslim countries.

That dismantling has led to layoffs and office closings for resettlement groups. And it has left refugees like Abdo with little hope that their families will be reunited.

“Refugee resettlement isn’t just a program. It is the way in which people find safety and the way in which people are reunited with their family members,” said Jen Smyers, director of policy and advocacy for the immigration and refugee program with Church World Service (CWS), one of six faith-based agencies authorized by the federal government to resettle refugees in the U.S.

Jen Smyers. Photo courtesy of Church World Service

Smyers told the story of one CWS client in Ohio who came to the U.S. more than two years ago. His pregnant wife was supposed to join him but had to reapply after she gave birth to their son.

The man still has never met his son.

“He Skypes with them every day, you know, but none of that can come close to holding your baby,” she said.

Smyers said that refugees get mixed signals from Americans. When they arrive at the airport, they are often met by the friendly faces of volunteers. But they then see and hear anti-refugee sentiment on the news.

Refugees ask if they are safe, if they are welcome, she said. They ask if they can share their stories without being deported. And they ask if they will have to flee again and seek refuge in another country.

“It shows the level of anxiety that people have about not being welcome where they finally thought they found a place where they could be safe,” Smyers said.

She worries about the policies that have limited the numbers of refugees allowed to resettle in the United States. And she worries about the rhetoric behind those policies, which paints refugees and immigrants as a threat.

The rhetoric has also vilified the refugee resettlement groups themselves, with tragic consequences.

When the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, experienced a horrific mass shooting on Oct. 2018 that left 11 dead and 7 wounded, reports emerged that the shooting suspect had not only posted anti-Semitic rants on social media, he had also railed against the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, one of the refugee resettlement agencies.

The synagogue had been an enthusiastic supporter of HIAS, a Jewish organization, and the suspect posted the following shortly before the attack: “HIAS likes to bring invaders in that kill our people. I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics, I’m going in.”

Melanie Nezer, senior vice president of public affairs at HIAS, said the incident has rocked her group but also triggered a surge in support.

“We were reeling from that tragedy, and still are in many ways,” she said. “Our commitment remains the same, or maybe even stronger, knowing that we have the support of our community and other faith communities that really believe in what we’re doing.”

Still, refugee resettlement groups like HIAS face an uncertain future.

A World Relief moving truck at a home to set-up for refugee resettlement. Photo by Viktoriya Aleksandrov via World Relief Spokane

Agency heads told RNS that in addition to widespread layoffs and staff reductions in the wake of lowered refugee admissions, they also consolidated programs after the U.S. State Department informed them it would no longer authorize funding for smaller offices — those expected to handle fewer than 100 refugees in fiscal 2018.

The nine agencies tasked with resettling refugees were also initially warned that the State Department might not renew funding for all of the agencies. Their funding for fiscal year 2018 was eventually authorized, but there were still reductions.

“Consistent with the FY 2019 refugee admissions ceiling, we worked closely with refugee resettlement agencies to align the program with expected arrivals while ensuring appropriate services are available for arriving refugees,” a State Department spokesperson told RNS, via email, when asked about the guidance it provided resettlement groups. “We will continue to base decisions on the location of resettlement affiliates on prioritizing family reunification to the extent practical and consideration of the local resettlement environment and economy.”

Cuts to the refugee resettlement program will have lasting consequences, says Smyers.

“You’re not just changing policy for a couple of years; you’re dismantling decades of work and relationships that will be nearly impossible to rebuild,” she said, referring to partnerships with local faith communities.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

FILE – In this June 14, 2015 file photo taken from the Turkish side of the border between Turkey and Syria, in Akcakale, Sanliurfa province, southeastern Turkey, thousands of Syrian refugees walk in order to cross into Turkey. Turkey has been building a concrete wall along parts of border with Syria, trying to shut down what has long been a jihadi highway for Islamic State group fighters crossing from Turkey into Syria. According to exclusive Islamic State documents leaked to the Syrian opposition news site Zaman al-Wasl and analyzed by The Associated Press, at least 4,000 foreign IS recruits traveled through Turkey into Syria between late 2013 and most of 2014. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis, File)

Bill Canny, executive director of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Migration and Refugee Service, said the government has pinpointed specific cities for downsizing, arguing there were simply too many refugee resettlement programs and not enough refugees.

He pointed to Dallas, Texas, where several refugee resettlement agencies — including the USCCB, which typically runs its programs through existing Catholic Charities chapters — have maintained robust programs for years.

“In Dallas, it’s been very, very difficult,” Canny said, adding that their program there has been “the hardest hit.”

Emily Gray, senior vice president of U.S. ministries at World Relief, said that since the start of fiscal year 2017, the country has lost one-third of its capacity to welcome and resettle refugees in local communities.

“That’s why I say the situation is still pretty dire. The downward pressure is still pretty extreme,” Gray said.

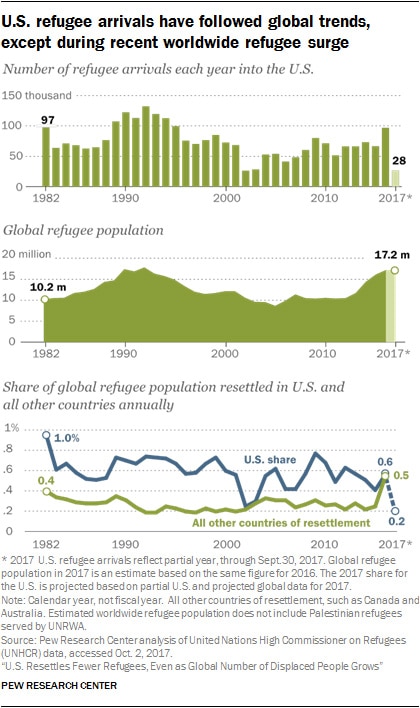

U.S. refugee arrivals have followed global trends, except during recent worldwide refugee surge. Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

During his first year in office, Trump set the number of refugees allowed into the U.S. at 45,000, a drop from 110,000 in Obama’s last year in office. The country actually admitted just a fraction of that number: 22,491 people.

The president set that number even lower this fiscal year, capping it at 30,000 people — the lowest in the history of the refugee resettlement program, which started in the 1980s.

“There’s nothing about this these last two years that looks like anything else that I’ve experienced with the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program,” said Kay Bellor, vice president of programs for Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service.

Asked if the government intended to resettle the full 30,000 refugees this year, a State Department spokesperson offered the following response via email: “The annual refugee resettlement ceiling is not a quota, but an upper limit on the number of refugees that can be resettled in a given fiscal year.”

Still, refugee resettlement agencies are at work.

This month Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS) will welcome its first Syrian refugees since the ban went into place, said Baylor.

After a “very, very difficult” year in 2017, she said, agencies spent the last year figuring out how to “ride through this incredible storm.”

“It’s not going away,” she said.

And while President Trump told the Christian Broadcasting Network in 2017 that he would make persecuted Christian refugees a “priority,” Canny said the number of Christian refugees has not increased since Trump took office.

U.S. President Donald Trump signs a revised executive order for a U.S. travel ban, leaving Iraq off the list of targeted countries, at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., on March 6, 2017. Photo courtesy of Reuters/Carlos Barria

RNS asked the State Department if the number or percentage of Christians has increased and if the administration was failing to live up to its promise to persecuted Christians. A State Department spokesperson emailed the following statement:

“The United States remains committed to advancing international religious freedom, including the protection of religious groups, across the globe. The United States will continue to resettle the most vulnerable refugees, including those who have fled religious persecution, while prioritizing the safety and security of the American people.”

While fewer refugees are arriving in the country, interest in volunteering with the faith-based agencies that resettle them has remained high.

“We have more churches and volunteers who want to work with refugees than we have refugees coming in,” said Smyers of CWS.

For CWS, that means helping refugees who have been in the U.S. for some time to take next steps: job training or with help writing a resume, applying for a green card or studying for the citizenship exam. It also means empowering and equipping refugees to make their voices heard.

Other agencies have focused their efforts on existing programs that help immigrants.

World Relief’s legal service and educational programs continue to grow even as layoffs have continued in its refugee resettlement programs. Some offices, like Chicago, won’t see any more refugee resettlement cases at least through the end of the year, Gray said.

At the same time, agencies have seen the “terrible impact of the retreat of the United States from its former leadership role” in welcoming the world’s refugees, Bellor said. They’ve seen families separated. They’ve seen them face the unknown.

Abdo now is pursuing her case through Community Refugee and Immigration Services, Church World Service’s refugee and immigration office in Columbus.

She talks “constantly” on the phone with her children in Ethiopia, she said through an interpreter. She works at a daycare and cares for her two youngest children, one born at a refugee camp in Libya and the other in the United States.

But, she said, “It is very hard and very difficult for a mother to be separated from her kids every day.”

In the meantime, Abdo is studying for her U.S. citizenship exam, which she hopes to pass this month.

She has nothing but positive things to say about her experience living in the United States. And she loves the American people, she said — she hopes they can understand her plight and advocate for her and her children in any way they can.

“I’m hoping that with time my situation will get better and I will be reunited with my children,” she said. “The only ask that I have for an organization or anybody who can help me with my situation is just to be an advocate for me.”