The Qumran caves, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, are located in the eastern section of the West Bank. Photo by Lux Moundi/Creative Commons

JERUSALEM (RNS) — When pieces of ancient pottery and never-before-seen scroll fragments began making their way to the antiquities black market a few years ago, archaeologists suspected that looters had found a new cache of Dead Sea Scrolls.

Determined to discover and protect whatever scrolls might still be hidden in the parched Judean desert, a joint team of archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Liberty University in Lynchburg, Va., began excavating some of the unexplored caves near Qumran, where all known Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the 1940s and 1950s.

“The concern was that the caves were being ransacked by locals who were illegally selling them,” said Randall Price, a professor of biblical and Judaic studies at Liberty University and co-director of the excavation, which began three years ago. “The Geneva Convention permits salvage excavations to try to recover items before they’re lost to history.”

Qumran, red pin, is located in an Israeli controlled area on the eastern side of the West Bank. Map courtesy of CIA/Creative Commons

If and when Price’s team unearths additional Dead Sea Scrolls or other artifacts, both Palestinians and Israelis will be sure to claim ownership.

The question of ownership comes at a particularly sensitive time in Israeli-Palestinian relations. Palestinian leaders have stepped up their bid for statehood by claiming that Jews are colonial invaders to the region and denying Jewish religious or historical ties to the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Israeli leaders counter by arguing both territories were parts of the biblical land of Israel, according to the Hebrew Bible.

On Dec. 31, Israel and the U.S. severed their membership in UNESCO, a world heritage preservation body, after it designated ancient Jewish holy sites such as the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron and Rachel’s Tomb in Bethlehem as Palestinian heritage sites.

Qumran is in the West Bank — territory Israel captured from Jordan during the 1967 Middle East War — which Palestinians say will be part of their future state.

Although international law assigns ownership of artifacts to the country where the excavation is taking place, the status of the disputed West Bank is not so clear-cut, some experts say. The Palestinians do not have an independent state, and Israel, which most countries consider an occupying force, has not annexed the territory.

Legally, a conquering nation is prohibited from removing artifacts from another’s land, “but with the West Bank, it’s not so simple,” said Aren Maeir, a professor of archaeology at Bar-Ilan University.

“It can be argued that the territory wasn’t conquered,” he said, referring to the territory’s history.

In 1947, the United Nations voted to create a Jewish state alongside an Arab state in then-British Mandatory Palestine.

The following year, Jordan and other Arab countries attacked Israel, hoping to destroy it. When that failed, Jordan seized control of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, but its rule was never recognized.

Many of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which contain the ancient Hebrew and Aramaic texts that form the basis of the Hebrew Bible’s canon, were discovered when Jordan ruled the territory from 1948 to 1967.

Under the 1993 Oslo Peace Accord, the Palestinian Authority was given civil control over large swaths of the West Bank, but not the Qumran region, in what is called Area C.

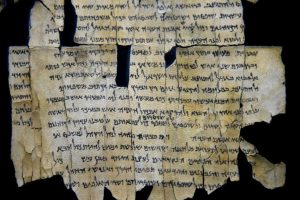

Part of Dead Sea Scroll number 28a (1Q28a) from Qumran Cave 1. Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin/Creative Commons

“This isn’t currently Palestinian territory, and I don’t think there is any substantive claim that objects found in Area C would have to be returned to the Palestinians,” Maeir said.

A report by the International Humanitarian Law Resource disagrees.

“Israel’s archaeological activities in Area C of the West Bank are in violation of its customary obligations under IHL, IHRL and the UNESCO legal framework,” the report states.

This view is shared by Ahmed Rjoob, general director of the World Heritage unit at the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

“The Dead Sea Scrolls and other artifacts belong to the Palestinians because they were found on Palestinian land. That applies even before 1948 when there was the British Mandate and during the years when Jordan ruled,” Rjoob said.

Rjoob said that “two or three months ago,” the Palestinian Authority asked UNESCO to pressure Israel into returning the scrolls and other artifacts to a museum in East Jerusalem, which Palestinians hope will be the capital of their eventual state.

Eugene Kontorovich, an international law professor at George Mason University in Arlington, Va., insists the Palestinians have no claims on the scrolls, the first of which were discovered by Bedouin shepherds who sold them to an antiquities dealer.

“The Palestinian government neither discovered them nor bought them. Indeed, a Palestinian Arab government did not even claim to exist at the time,” he said. “As a matter of cultural rights, these artifacts are part of the historical posterity of the Jewish people, and arguments to the contrary are attempts to erase Jewish history.”

The scrolls and other artifacts simply have nothing to do with the Palestinians, Kontorovich said.

Price cannot envision Israel ever giving the items to the Palestinians.

“This has been a long-standing request by the Palestinians, but frankly, everyone I know in the Israeli government or antiquities administration rejects this outright,” he said. “They see the Palestinians trying to make a political statement. Because if Israel says the Palestinians have a right to the artifacts, you might as well say all the land is theirs as well.”

Palestinians, Price said, claim that the scrolls and related artifacts are part of their history and culture. But he argues that “there was no known Palestinian people” at the time the artifacts were created.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, he said, help scholars understand Jewish texts, customs and laws. Many of them are copies of the Hebrew Bible and are written in Hebrew and Aramaic.

As such, they should reside in Israel, he said.

“This isn’t about politics and religion and ownership but saving the past from being lost to the people whose heritage this is,” he said.