Members of Jehovah’s Witnesses wait in a court room in Moscow, Russia, on April 20, 2017. Russia’s Supreme Court banned the Jehovah’s Witnesses from operating in the country, accepting a request from the justice ministry that the religious organisation be considered an extremist group, ordering closure of the group’s Russia headquarters and its 395 local chapters, as well as the seizure of its property. (AP Photo/Ivan Sekretarev)

MOSCOW (RNS) — A Russian court has sentenced a Danish member of the Jehovah’s Witnesses to six years on extremism charges in a case that has rekindled memories of the Soviet-era persecution of Christians and triggered widespread international criticism.

Dennis Christensen, a 46-year-old carpenter who has lived in Russia for more than two decades, was sentenced on Wednesday by a court in Oryol, a city some 200 miles south of Moscow.

The Danish national had spent almost two years in a pre-trial detention facility after being detained by armed police and officers from the FSB security service during a raid on a Jehovah’s Witness prayer hall in Oryol in May 2017.

Christensen is the first Jehovah’s Witness to be sentenced to prison in Russia since the country’s Supreme Court declared the pacifist Christian denomination an “extremist organization” in 2017, putting it on par with the Islamic State militant group and neo-Nazi movements.

The Supreme Court claims Jehovah’s Witnesses promote the “exclusivity and supremacy” of their beliefs.

Judges of Russia’s Supreme Court attend a hearing in Moscow, Russia, on Jan. 23, 2014. Photo by Maxim Shemetov/Reuters

Prosecutors said Christensen had organized the religious activities of the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Oryol, an offense that carries a maximum sentence of 10 years behind bars. They did not cite, however, any specific examples of what exactly was “extremist” about his actions.

His wife, Irina Christensen, a Russian national, said the allegations against her husband were “absurd” and that he was a law-abiding person.

His attorney spoke to reporters in Moscow on Friday (Feb. 8).

“Nothing Christensen did posed any danger to society,” Anton Bogdanov, Christensen’s attorney, said at a press conference. Bogdanov also said that the court’s decision had effectively criminalized “peaceful religious practices” such as praying, singing hymns and Bible study.

Scores more Jehovah’s Witnesses have also been charged with participating in or organizing the group’s activities. Twenty-five Witnesses are behind bars awaiting trial or being tried, while another 24 are under house arrest.

There are an estimated 175,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia. Many converted to the faith after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Around 5,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses are estimated to have fled the country since the Supreme Court outlawed the group two years ago.

Many say they fear that their children could be taken away from them by the state.

The Kremlin’s crackdown on the Jehovah’s Witnesses has been accompanied by a wider state campaign against “foreign religions” amid tensions with the West over Syria and Ukraine.

In 2016, President Vladimir Putin, as part of vaguely worded anti-extremism and terrorism legislation, approved a law that outlawed missionary work carried out in Russia by groups like the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Baptists, and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Michelle Bachelet, the United Nations’ High Commissioner for Human Rights, denounced the court’s decision in the Christensen case.

Danish citizen Dennis Christensen was detained in Oryol, Russia, after a Jehovah’s Witness service was raided. Photo courtesy of Jehovah’s Witnesses

“The harsh sentence imposed on Christensen creates a dangerous precedent, and effectively criminalizes the right to freedom of religion or belief for Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia — in contravention of the state’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” Bachelet said in a statement.

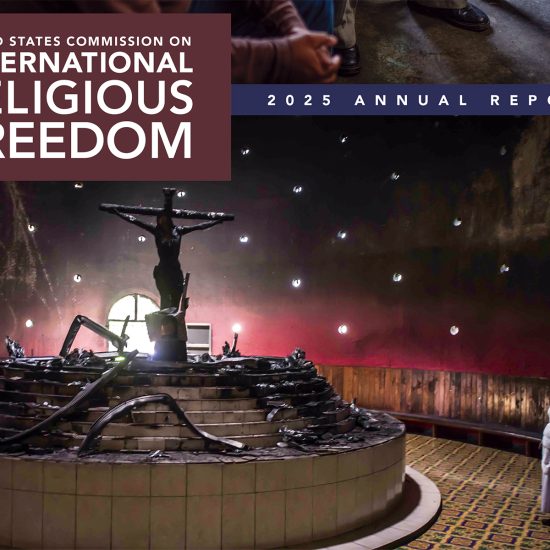

Russia’s decision to imprison Christensen was also criticized by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, a bipartisan government advisory body, and the European Union.

“Dennis Christensen has been arrested and prosecuted by the authorities simply for practicing his religion as a Jehovah’s Witness,” said Amnesty International in a statement.

Danish Foreign Minister Anders Samuelsen expressed serious concerns about the sentence and called on Russia to “respect freedom of religion,” comments that were echoed by Andrea Kalan, a spokeswoman for the U.S. embassy in Moscow.

Valery Borshchev of the Moscow Helsinki Group human rights organization warned that the imprisonment of Christensen could trigger a “wave” of arrests of members of other minority religious groups in Russia, not only Jehovah’s Witnesses.

“Adventists, Baptists, and so on, should be very concerned,” he said.

While there was little doubt that Christensen would be found guilty of the charges against him — very few criminal cases end in an acquittal in Russia — the harshness of the sentence came as a surprise, because Putin said last month that it was “complete nonsense” to classify the Jehovah’s Witnesses as an extremist organization.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses are Christians, too. I don’t quite understand why they are persecuted,” Putin said at a meeting with human rights defenders in Moscow.

The imprisonment of Christensen dashed hopes, however, that the Russian State’s two-year-long campaign against the Jehovah’s Witnesses was nearing an end.

Alyona Vilitkevich, whose husband, Anatoly, is also facing prison after being charged with organizing the activities of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Ufa, a city in central Russia, said she was dismayed by the six-year sentence handed down to Christensen.

“I’m afraid for my husband and for my family. Will I really have to be apart from my husband for six years just because we are ordinary believers who read the Bible and try to live by it?” she told RNS.

A group of Jehovah’s Witnesses writes letters to members of the Russian goverment in support of their churches in Russia. Photo courtesy of Jehovah’s Witnesses

Paul Gillies, international spokesman for Jehovah’s Witnesses, called Christensen’s conviction “unjust” and said it had “dangerous implications.”

Jehovah’s Witnesses have a well-established international reputation for being peaceful, law-abiding citizens,” Gilles said in a statement to RNS. “It is our hope that the Russian authorities will take this opportunity to correct the unjust decision to ban our activities, which has caused the imprisonment of our fellow believers.”

The court’s decision appeared initially to have caught the Kremlin unawares.

“They could not have done this simply for practicing his religion,” Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told the RIA Novosti state news agency on Wednesday. “Presumably, there were some grounds for the accusations.” Peskov admitted, however, that he did not know exactly what these grounds were.

In additional comments on Thursday, Peskov said the issue was “complicated” but insisted that the activities of the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia were in violation of the country’s law.

“We can’t operate with common-sense concepts for state purposes,” Peskov said. “First and foremost, we operate with concepts of legality and illegality. In this case, the activity of this religious organization is illegal.”

Human rights defenders responded by saying that during the Soviet era, religious groups were also outlawed and persecuted.

Some 200,000 members of the clergy were murdered during the first two decades of the Soviet era, according to a 1995 Kremlin committee report, while millions of other Christians suffered for their faith.

Although Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin allowed a limited revival of the Russian Orthodox Church during the Second World War, anti-religion propaganda and discrimination against believers continued up until the mid-1980s. Today, more than 80 percent of Russians identify as Orthodox Christians, although few attend church services or observe religious fasts.

The Russian Orthodox Church, a key Kremlin ally, has supported the Kremlin’s clampdown on the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Vitaly Milonov, an ultra-conservative lawmaker with close ties to the Russian Orthodox Church, told RNS that he considered the Jehovah’s Witnesses a “zombie sect” and insisted that Russia was within its rights to outlaw any religious groups it believed to be a threat to the public well-being.

There were signs, though, that the church was uncomfortable about the move to imprison Christensen. Vakhtang Kipshidze, a spokesman for the Moscow Patriarchate, declined to comment on the court’s decision but said that Christensen’s “religious beliefs, in our opinion, are his personal business and the subject of free choice.”

Archpriest Vyacheslav Perevezentse was another to speak out. “(Jehovah’s Witnesses) were recognized as an ‘extremist organization’ on very unclear grounds. They did not prepare or commit terrorist acts, nor were they known to have committed large-scale fraud,” he wrote in an article published by Russia’s Pravmir website.

“Could they come for us? Easily,” he added. “If it’s necessary, they’ll come. After all, they’ve already come before, and on more than one occasion.”