An illustration of the flight path of the Beresheet spacecraft to the moon. Image courtesy of SpaceIL

(RNS) — As engineers at Israeli nonprofit SpaceIL prepared for the launch of their lunar lander last year, they did what most aerospace engineers do: They checked and rechecked every element of their tiny spacecraft, planning for all conceivable issues that could hinder its journey to the moon.

At least one also worried about the calendar.

SpaceIL system engineering manager Alexander Friedman, who is in charge of all operations for the group’s “Beresheet” lander after launch, identifies as an Orthodox Jew. As such, he does not work on Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath that lasts from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday.

But SpaceX, the American aerospace company SpaceIL partnered with to catapult its lander into orbit, typically launches its rockets on Saturdays.

The Beresheet spacecraft in the clean room during construction. Photo by Alex Polo, courtesy of SpaceIL

“Because I am religious guy, I am forbidden to work on Saturday, except (in a) very extreme situation,” the 68-year-old Friedman told Religion News Service.

He said that fact led to many “long discussions” between SpaceIL and SpaceX, with hopes of moving the launch to a different day of the week.

SpaceX declined to comment when asked about those discussions, but it appears the issue was eventually ironed out: The SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket blasted off into space with Beresheet aboard on Thursday, Feb. 21, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, at 8:45 in the evening — which is just before 4 in the morning on Friday in Israel.

The Beresheet spacecraft lifts off aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket on Thursday, Feb. 21 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. Photo courtesy of SpaceIL

The launch time was just one of many religious elements surrounding the Israeli Beresheet lander, whose name is a reference to the Hebrew word for “in the beginning” that introduces the biblical book of Genesis. Not only is the spacecraft — which is carrying copies of Jewish prayers and holy texts — poised to make history for Israel and the privately funded space industry, it’s also quietly modeling for the broader aerospace industry how religion and science work together to reach the stars.

Originally conceived in a Tel Aviv bar in 2010 by an Israeli a computer engineer and two of his friends, Beresheet was designed as an entry in Google’s Lunar X Prize competition, which offered $20 million for the first privately financed group to land a robotic spacecraft on the lunar surface.

The contest eventually concluded without a victor in January 2018 (although SpaceIL was a finalist), but the Beresheet team — which had spent years crafting a lander to be as inexpensive as possible — pressed on. Unlike its business-focused competitors, SpaceIL had secured funding from philanthropists who believed in the cause, securing windfalls from billionaires such as Morris Kahn, an Israeli telecommunications mogul, and prominent American Republican Party donor Sheldon Adelson.

The result was a lander-on-a-budget that would hitch a ride on a SpaceX rocket with the primary goal of inspiring Israeli schoolchildren to learn more about space and engineering. It’s also carrying religious cargo: The lander is toting a time capsule of digital discs stuffed with files that include Israeli symbols, a Bible and a copy of the Wayfarer’s Prayer — a prayer for safe journey often recited by Jews.

A separate “Lunar Library” provided by the Arch Mission Foundation is also aboard Beresheet and includes texts from multiple world religions housed within a massive “30 million page archive of human history and civilization” device that resembles a DVD.

“The Lunar Library contains Old and New Testaments in many editions and languages,” Nova Spivack, co-founder of the Arch Mission Foundation, told RNS via Twitter. “It also contains all other world religions, as any good library should.”

Yariv Bash, from left, Yonatan Weintraub, and Kfir Damri insert the time capsule into the Beresheet spacecraft. Photo courtesy of SpaceIL

Before the launch, Friedman told the Cleveland Jewish News that he had a prayer composed for the mission expressing hope that God will “lead our spacecraft to peace and bring it to peace, and save it from all sorts of malfunctions, and allow us to see it reach the moon in peace.”

Malfunctions are a key concern for the mission as, in keeping with its thrifty approach, Beresheet is using a scrappy, cost-effective method to make its way to the moon. Instead of blasting off and immediately beelining to earth’s silvery satellite, the tiny lander entered into orbit around the Earth and is slowly elongating its path into ever-wider rotations using small, fuel-saving maneuvers.

The Lunar Library includes a large history of humans and civilization. Photo by Bruce Ha/ Arch Mission Foundation

The plan is to extend its elliptical rotations until it is captured by the moon’s gravity, at which point the lander can touch down and complete its brief mission — primarily gathering imagery and studying the moon’s magnetic field — before deteriorating in the lunar heat.

Friedman said he and his team work to time maneuvers on days that don’t overlap with Shabbat. It’s an additional complication for an already time-consuming approach that takes more than a month and a half. Engineers don’t expect Beresheet to attempt its moon landing until April 11.

The ride so far hasn’t been without hiccups, either. Just days after launch, Beresheet’s computer unexpectedly reset itself, prompting SpaceIL engineers and its partner Israel Aerospace Industries to cancel a maneuver until the situation was eventually straightened out.

Even so, the atypical approach does give the lander ample time for epic views: It has sent back several spacefaring “selfies” featuring planet Earth hovering in a black void just above a sign strapped to the side of the lander. The banner bears an image of a waving Israeli flag next to two slogans — one in English that reads “Small country, big dreams” and another in Hebrew that translates to “the Jewish people live.”

A selfie taken by the Beresheet moon lander spacecraft while roughly 23,350 miles from Earth. Image courtesy of SpaceIL

For Friedman, a veteran engineer who worked in spaceflight for 35 years — including serving as system engineering manager and launch and early orbit phase mission manager for various “Amos” Israeli communications satellite missions — such moments are a reminder of why he does his work in the first place.

“I don’t see any contradiction between these two — science and religion,” he said, noting that he has shifted his work schedule in past missions to accommodate Shabbat. “From a religious point of view, at least in my opinion … we want to know as much as possible what God (does).”

Friedman’s sentiments were echoed by Rabbi Geoffrey Mitelman, founding director of Sinai and Synapses, a group that seeks to “bridge the scientific and religious worlds.” Mitelman noted that Beresheet is hardly the first instance of religious expression in space, pointing to when U.S. astronaut Buzz Aldrin, a Presbyterian, celebrated Christian Communion on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. It’s not even the first time the Book of Genesis has reached orbit: Jewish astronaut Jeffrey Hoffman read Genesis from a Torah scroll while aboard the space shuttle Columbia in 1996, and the Washington National Cathedral recently commemorated the 50th anniversary of when Apollo 8 astronauts broadcast themselves reading from the opening verses of the book while circling the planet.

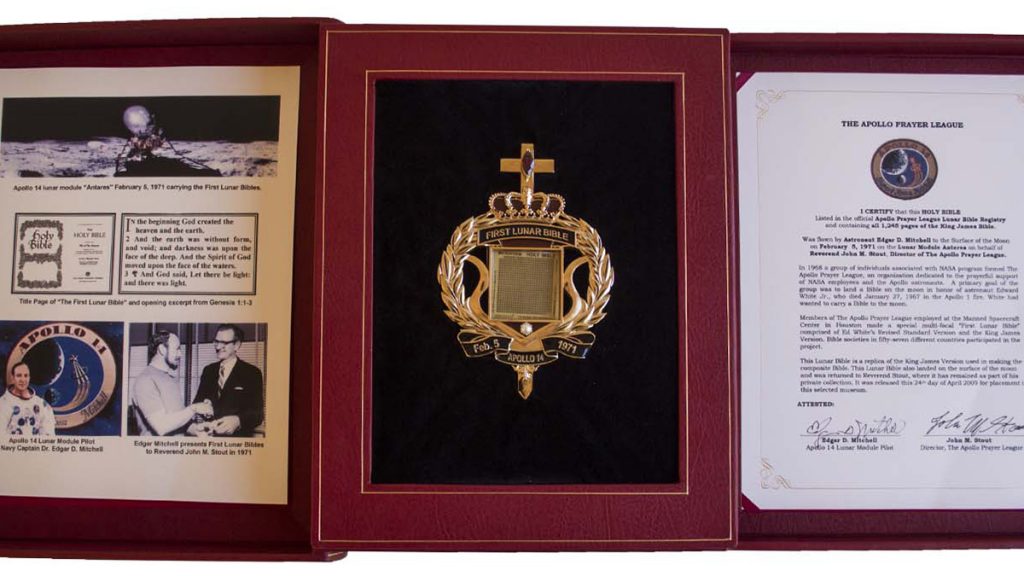

In fact, the first time a complete holy scripture touched down on the lunar surface was in 1971, when astronaut Edgar Mitchell toted along microfilmed copies of the King James Bible on Apollo 14.

The microform copy of the Apollo 14 lunar-landed King James Bible and other related items available for auction. Image courtesy of Nate D. Sanders Auctions

Mitelman said such religious expressions not only offer a glimpse of humanity back on Earth, but also use the power of religious language to capture the awe-inspiring nature of space travel.

“At its best, religion gives us a sense of humility, wonder, appreciation, and it gives us the language that we wouldn’t have otherwise,” Mitelman, who is ordained in the Jewish Reform movement, said. “I think it’s incredibly wonderful and powerful that Israelis are going to be doing that through a Jewish expression.”

As for Friedman, he argued that when religious people like himself study science, they want to understand God’s “doing” and explore God’s “nice order … and see how it’s beautiful.”

If all goes well, a successful moonshot would not only make SpaceIL the first privately funded lunar lander in history, but also allow Israel to join an elite club of only three other countries that have landed something on the moon — the United States, Russia and China.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, center, joins others to watch the successful launch of the Beresheet spacecraft aboard a SpaceX rocket on Feb. 21, 2019. Photo courtesy of SpaceIL

For Friedman, the mission also carries with it a meaning that is equal parts religious and familial. He is originally from Russia, where he says his father was thrown in jail during the Soviet era as part of the government’s systematic targeting of Chabad-Lubavitch Jews in the region.

His father was charged with helping other Jews immigrate to Israel illegally, and he subsequently spent “10 or 15 years” in prison. Friedman didn’t meet him until around age 6 1/2.

Back then, many Jews in Soviet Russia were afraid to even claim their faith aloud. But a generation later, Friedman is sending Jewish texts and prayers to the moon.

“It’s something very special, and not usual,” he said.