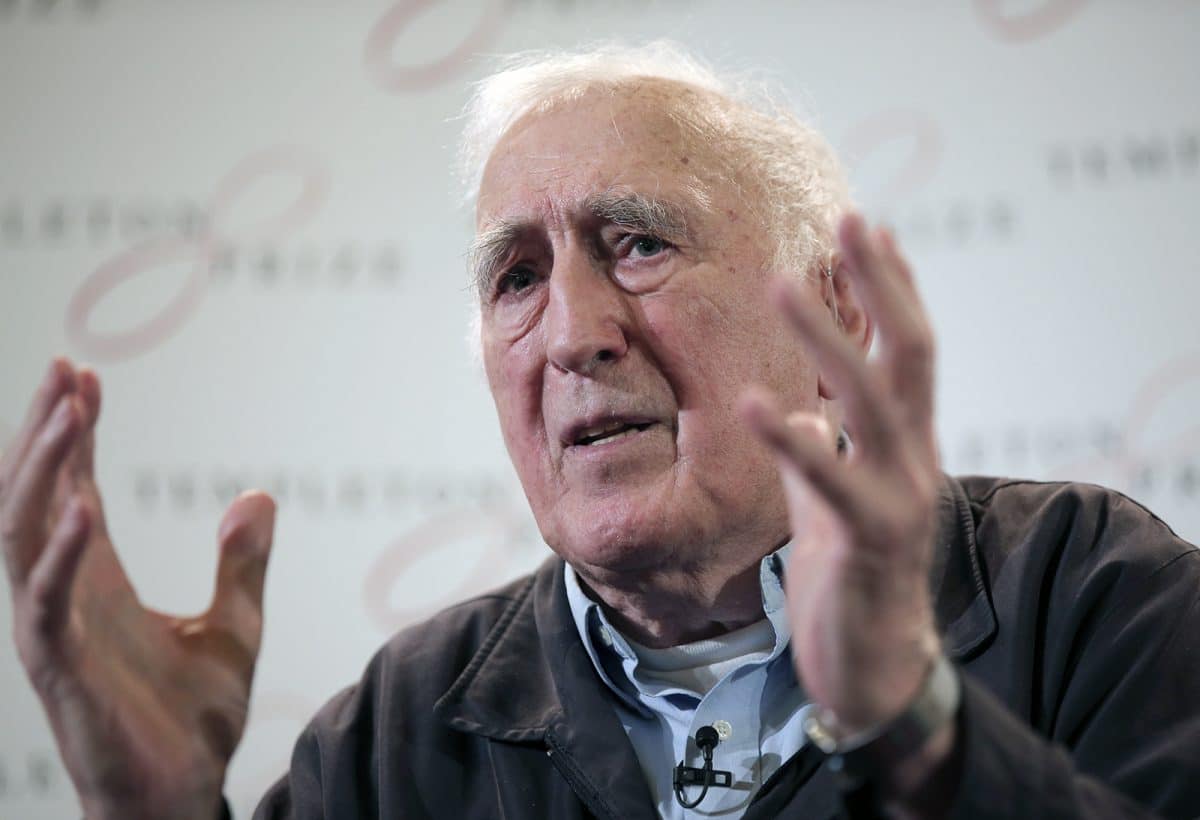

Jean Vanier, the founder of L’ARCHE, an international network of communities where people with and without intellectual disabilities live and work together, gestures as he talks during a news conference, in central London, on March 11, 2015. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis)

(RNS) — Jean Vanier’s ministry to people with developmental disabilities began with a simple gesture: He invited three men who had spent the majority of their lives in a large institution to come and live with him.

The four settled into a house in the small village of Trosly-Breuil in France in 1964. Soon more homes opened, and L’Arche, a worldwide network of homes where people with and without intellectual disabilities live and work together as peers, was born.

Vanier, a Catholic who believed people with developmental disabilities were intrinsically worthy and had something to give and teach others, died Tuesday (May 7) at age 90 in France.

A winner of the Templeton Prize and numerous other honors, Vanier (pronounced Van-YAY), transformed the way people think of caring for the disabled.

But his impact was just as great on Christian ethics.

“He was a person of profound humility that was able to see into the heart of disabled people and know that they were fully human,” said Stanley Hauerwas, a Christian ethicist and Duke Divinity School professor emeritus.

Hauerwas, who co-authored a book with Vanier, “Living Gently in a Violent World: The Prophetic Witness of Weakness,” said Vanier challenged people’s presumptions of self-importance and showed that the least presentable people are part of God’s plan and, indeed, its very core.

Jean Vanier shaking hands with one of the core members of L’Arche Daybreak, John Smeltzer, in October 2009. Photo by Warren Pot/Creative Commons

It was not a given that Vanier should devote his life to people at the margins. He was born into a prestigious, well-to-do Canadian family. His father was the British monarch’s representative in Canada, the governor general. Vanier trained for a career as a naval officer with the British and later Canadian navies but then resigned his commission and went to France, where he earned a doctorate in philosophy. His appeared to be a life of upward mobility.

Butt in 1964, he decided to follow his mentor, a Dominican priest named Thomas Philippe who had become a chaplain to a small institution for people with disabilities. Wanting to be close to him, and horrified by the way disabled people were treated in institutions, Vanier bought a house nearby and took in people with profound developmental and intellectual disabilities.

“The cry of people with disabilities was a very simple cry: Do you love me? That’s what they were asking,” Vanier wrote. “And that awoke something deep within me because that was also my fundamental cry.”

While the L’Arche organization — the word means arch or bridge — was sometimes critiqued for not addressing policy concerning people with disabilities, it was also prized for offering homes where disabled and able-bodied could live side by side as equals. Daily rituals, such as meals, prayers and birthday celebrations, are shared.

Susan McSwain, who co-founded a Durham, N.C.-based Christian nonprofit that offers various programs for developmentally and intellectually disabled people, said Vanier was a major influence on her work.

In particular, she cited Vanier’s commitment to mutuality in friendship.

“A lot of work with people with disabilities comes from a mindset of someone who has something to give somebody who doesn’t have something,” said McSwain, the co-founder of Reality Ministries. “It’s a one-way street. Jean Vanier turned all that on its head by saying, ‘We’re incomplete without each other.’”

His work was also distinctly Christian, though L’Arche homes are ecumenical and interfaith.

Vanier talked of the brokenness of both the disabled and the abled, and of the transformation that can happen through relationships of mutuality. He also founded a similar organization, Faith and Light, which consists of small groups that meet regularly to support and celebrate people with developmental disabilities.

“I’m not interested in doing a good job,” he wrote. “I’m interested in an ecclesial vision for community and in living in a gospel-based community with people with disabilities.”

Jean Vanier. Photo courtesy of Templeton Prize, John Morrison

Bill Gaventa, who directs the Summer Institute on Theology and Disability, said the homes created by L’Arche — there are now 150 communities in 38 countries — were meant to be spiritual.

“At the heart of that community was the sense of spirituality and a spiritual journey that they were all undergoing together,” Gaventa said. “For him, it was about being called to be with the marginalized, the weak and the wounded, or as the Apostle Paul would say, ‘the foolish,’ and what we learn there, rather than from the powerful and the mighty.”

L’Arche homes function much like extended families, said Tom Murphy, who has lived in a L’Arche community since 2002 and serves as a member of the board of directors for L’Arche Boston North.

“L’Arche is a place that provides services and care and licenses with the state to make sure disability services are carried out with excellence,” said Murphy, who is writing his doctoral dissertation on Vanier. ‘But along with that is family.”

For Vanier, who never married and early in life considered the priesthood, living among people with disabilities was a religious calling.

Yet Vanier was also a man who loved to laugh and play. He spoke frequently about how his friends with intellectual disabilities taught him how to have fun and not to take life too seriously, Murphy said.

James Martin, a Catholic priest and the editor at large at America, a national weekly magazine published by the Jesuits, was quoted as saying of Vanier, “During his life, there was no one I thought more deserving of the title ‘living saint.’”