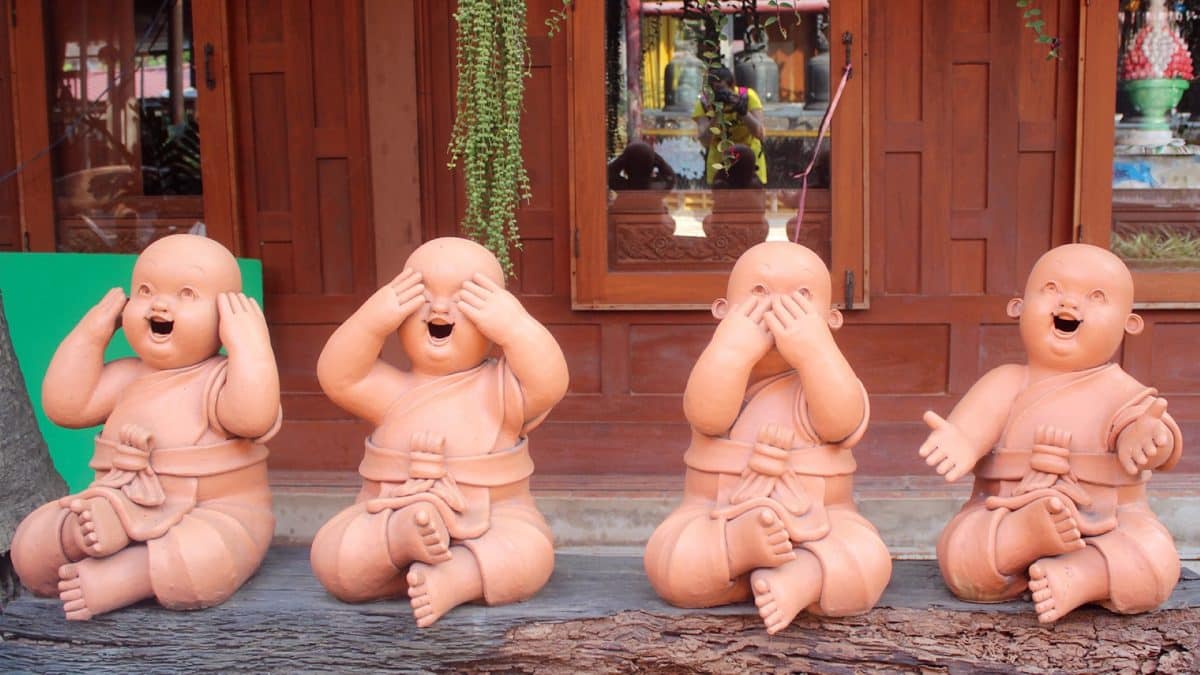

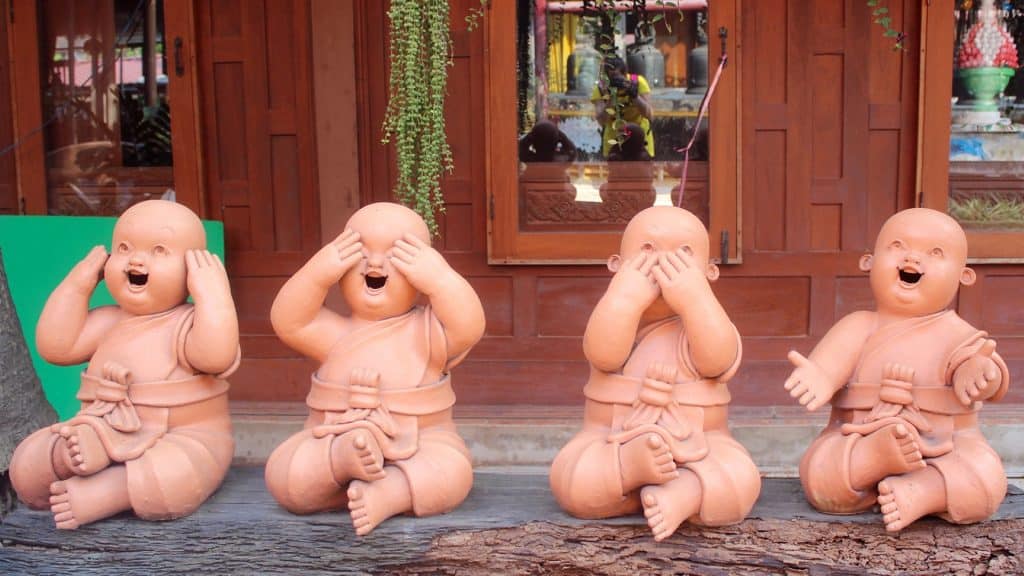

Child buddha garden statues. Photo by Peggy und Marco Lachmann-Anke/Pixabay/Creative Commons

(RNS) — Shopping at Walmart a few years ago, David Morgan saw a statuette of Santa Claus praying on one knee before a cross and knew he had to have it.

Morgan, a professor and religious studies chair at Duke University who studies religion, culture and media, was amused by the pious Santa Claus, whose costume derives from Thomas Nast’s 1860s Harper’s Weekly cartoons and Coca-Cola ads starting in the 1930s.

He doesn’t think the statue mocks Christianity. Instead, he thinks it pokes fun at the ways capitalism reshapes the sacred.

An “Adoring Santa” statue features Santa kneeling at a manger scene. Photo via Autom.com

But the people who buy the statue probably don’t care.

“I imagine some Christians even admire it as a way of ‘putting Christ back in Christmas,’” he said.

Still, the line between well-intentioned kitsch and bad taste is blurry.

Amazon removed dozens of items, including bathmats with Quranic script, from its digital shelves earlier this year after criticism from the Council on American-Islamic Relations. And for at least several years, controversial activist Rajan Zed has complained about Amazon’s hawking of toilet seat covers with Hindu imagery.

Part of the challenge, said S. Brent Rodriguez-Plate, associate professor of religious studies at Hamilton College and author of “Blasphemy: Art That Offends,” is that both kitsch and offense are necessarily in the eye of the beholder.

“Toilet seat covers with the name of Allah, or a swimsuit with the goddess Lakshmi on it, or a Jesus statue made out of cheese will offend people,” he said. “People have the right to be offended.”

When Plate was researching hundreds of provocative artworks — such as Andres Serrano’s photo of a crucifix immersed in urine — he found that many of the artists intended to provoke. Serrano’s piece, he said, is a great example of art’s capacity to generate conversations about the value of art and of religious objects.

S. Brent Rodriguez-Plate. Photo by Joshua D. McKee

But not all blasphemous artworks are the same, he said. Some are art. Others are more like Jesus junk.

Many people create religiously offensive works just to offend, Plate said.

“People believe they have the right to market or publish any potentially offensive thing, because they claim they are asserting freedom of speech,” he said. “In reality they are just setting up clickbait or trying to sell something.”

Commercial producers of religious kitsch try to figure out what’s likely to sell while avoiding the offensive, said Morgan.

Garden stores, for example, are likely to sell a variety of Buddha and St. Francis statues for use as garden ornaments.

“Neither one is being used to venerate the sacred person portrayed,” Morgan said. “It works, because no one seems to be offended.”

But vendors can’t really know ahead of time what will and won’t offend religious believers.

“One never knows where the line will be located until a group responds,” Morgan said. “That imprecision of locating the limit of propriety depends entirely on who is offended and under what circumstances.”

Popular culture often references religion without either offending or affirming religious people, as is the case with second-rate Buddha statues.

David Morgan. Photo courtesy of Duke

But such imagery would be treated differently in parts of Asia than it is in the United States, according to Morgan.

“Some Hindus and Muslims may be offended at the use of imagery or objects drawn from their traditions, because they regard the act as disrespectful and do so within the context of a truculent Hindu nationalism or in the face of a bias against conservative Muslim practices,” he said.

Still, commercial vendors aren’t targeting such true believer with their products.

“They are looking instead for secular, Western or liberal Indians or Muslims who respond to commercial ‘kitsch’ in much the same way that I responded to the praying Santa Claus,” Morgan said. “Such items are amusing, not devotional.”

Terrence Dempsey, a Jesuit priest and director of St. Louis University’s Museum of Contemporary Religious Art, wasn’t offended when artist Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt — who was at Stonewall Inn the night of the riots — gave him one of his “Charmin bathroom tissue” angels.

“There is a playfulness about his work, but when dealing with religious imagery he means no disrespect,” Dempsey said. “He came from a working-class Catholic family in New Jersey, and he began making icons and altar assemblages out of glitter, aluminum foil, Saran Wrap and staples. He once told me that his art is about the ‘glow’ and not the ‘gold.’”

When considering religious kitsch, it’s important to differentiate between majority and minority cultures, warned Plate.

“In the United States, for instance, this means that people might need to think more carefully about representations of Muslims, Jews and Hindus, among others, as it’s a dominantly Christian culture,” he said.