A U.S. $20 bill from the offering plate at Hope Central Church in Boston is stamped with the face of abolitionist Harriet Tubman on June 2, 2019. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

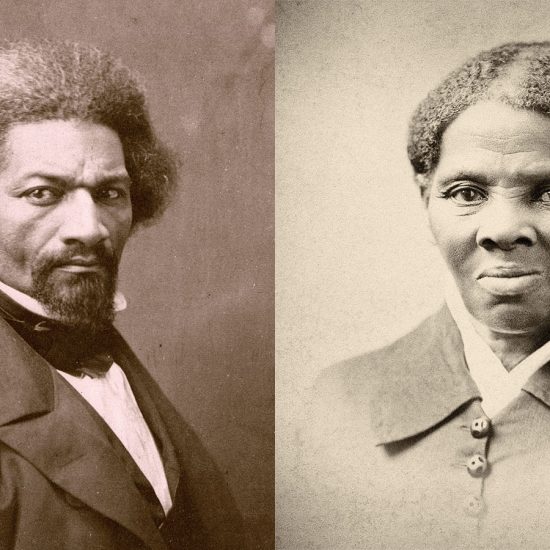

BOSTON (RNS) — Three years ago, the Treasury Department announced that it would put Harriet Tubman’s face on the front of the $20 bill by 2020. A portrait of the abolitionist, championed by activists, would replace that of President Andrew Jackson, who would be moved to the back of the bill.

Then, two weeks ago, the government walked back its plan. The image’s redesign likely would not come up until 2028, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin declared.

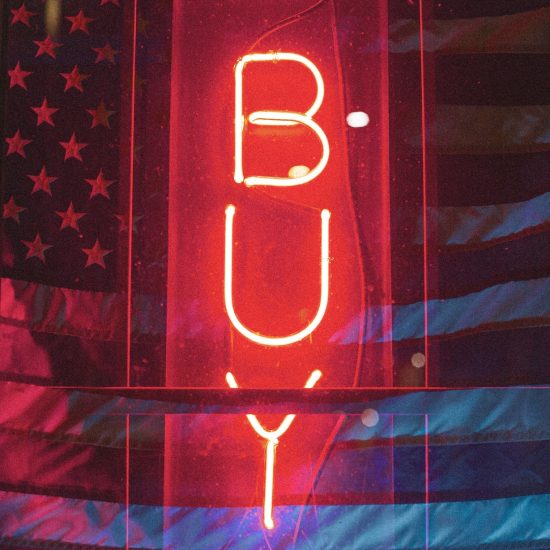

But that didn’t end the matter at Hope Central Church in Boston. “The U.S. Treasury said they will not,” Pastor Laura Ruth Jarrett told her congregation in the city’s diverse Jamaica Plain neighborhood this week. “And we say we will.”

Hope Central Church in Boston, on June 2, 2019. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

Since May 2, the church, affiliated with the United Church of Christ and Disciples of Christ, has been stamping all $20 bills from its offering plates with Tubman’s face. It is, Jarrett said, a “worthy replacement.”

“I’m taking such pleasure in this. Mr. Trail of Tears, gone!” laughed Ann Potter, who counts offerings for HCC, as she covered the former president’s face on bill after bill. “Andrew Jackson is not my favorite president.”

Records show that Jackson, the country’s seventh president and a staunch anti-abolitionist, owned as many as 160 slaves. His role in the forced relocation of an estimated 60,000 Native Americans, in part to expand U.S. slave ownership and make room for more plantations, led to the death of tens of thousands of native people. More than 4,000 Cherokees, who nicknamed him “Indian killer,” died on their march west along the Trail of Tears.

Tubman, who was chosen from thousands of nominations as the new face of the $20 bill, would have become the first African American on paper money. The addition of Tubman to the bill was planned for next year, to mark the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in America.

After Tubman escaped the Maryland plantation where she was born into slavery, she returned to the South to help hundreds of other enslaved people to freedom through the Underground Railroad. Later, she worked as a Union spy during the Civil War.

Congregant Marylou Steeden said she has noticed the number of $20 bills in the church’s Sunday plate increase since the church began stamping them. On Sunday (June 2), after their Ascension Day service, they collected eight $20 bills.

“Everyone who does this just gets giddy about it,” Steeden said. “It just feels so good, like a little rebellion.”

A U.S. $20 bill is stamped with the face of abolitionist Harriet Tubman at Hope Central Church in Boston, on June 2, 2019. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

The stamps were originally created by Brooklyn, N.Y., designer Dano Wall two years ago as part of an effort to ignite conversation about the delayed plan to replace Jackson’s image. “Putting Harriet Tubman on the front of the $20 bill would have constituted a monumental symbolic change, disrupting the pattern of white men who appear on our bills,” he told The Washington Post. Wall has sold hundreds of the stamps online, giving the proceeds to charity. His blueprint of the stamp for a 3D printer is available for free.

Hope Central Church congregant Greg Buckland, who teaches at a community makerspace known as a Fab Lab in the nearby Dorchester neighborhood, printed out the 3D design for the church, a process that involves about $2 worth of 3D printer filament and $2 worth of rubber, he said.

Another local minister has already reached out to ask Buckland to produce another stamp for his congregation. The project makes for a great pairing between congregations and local makerspaces, he said.

“When Rev. Laura Ruth approached me about making the Tubman Stamp, I was excited, because our Fab Lab serves predominantly low-income and people of color communities, and this aligns with our values of justice and inclusion,” Buckland explained via email.

Rev. Laura Ruth Jarrett leads worship at Hope Central Church in Boston, on June 2, 2019. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

Hope Central Church is considering becoming a stamping station for anyone seeking to stamp their dollar bills with Tubman’s image.

The mostly white congregation, formed in the spring of 2010 through the merger of two local church communities, prides itself on its inclusivity and commitment to racial equity. A large “Black Lives Matter” poster hangs above the entrance to the church, and a “Stand Against Racism” poster hangs inside.

The church’s volunteer racial justice team meets with Jarrett monthly to brainstorm ways to serve local communities. Later this week, church leaders will participate in a Black Lives Matter vigil, and next year, they hope to lead a “pilgrimage” to Alabama’s new memorial to victims of lynching.

The Ascension Day service included prayers for all people affected by gun violence, debt, addiction, the school-to-prison pipeline and other local crises and began with a welcome message to “people of all colors, cultures, abilities, sexual orientations and gender expressions.”

“We do not value the colonialism of white supremacy,” Jarrett told her congregants. “…Our work is not to provide charity, but rather to provide reparation, to give back what we stole.”