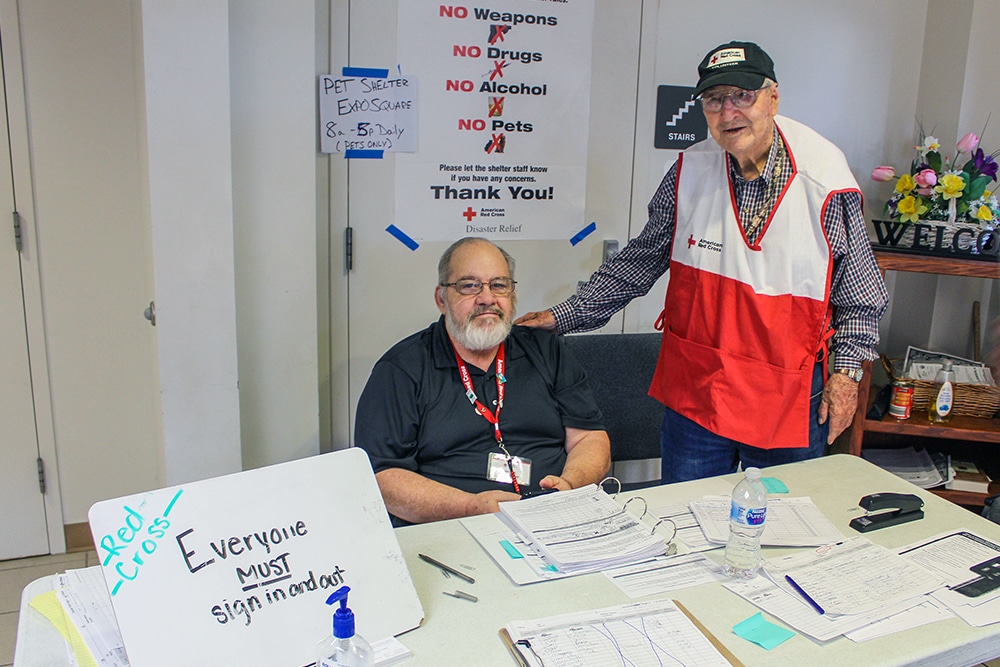

Kenneth Hearrell, right, is the “disaster deacon” for the Crosstown Church of Christ in Tulsa, Okla. RNS photo by Bobby Ross Jr.

TULSA, Okla. — Oh, Kenneth Hearrell has stories to tell.

About how he rode a horse five miles to his two-room schoolhouse from first through fourth grades.

About how he used a homemade row boat to drive cattle to dry land after a big rain swamped the Texas side of the Red River.

About how his Morse code skills got him sent to Germany, while the rest of his U.S. Army artillery platoon was dispatched to Korea during the war.

“So the code saved my life,” the retired air traffic controller said.

But ask the 87-year-old Hearrell about his role as the “disaster deacon” for the Crosstown Church of Christ — a 300-member congregation that served for nearly a month as an emergency shelter for victims of historic flooding along the Arkansas River — and he has less to say.

It’s as if he can’t understand why anyone would need to ask why he feels compelled to help.

“I do it because I can,” said Hearrell, sporting a red-and-white American Red Cross volunteer vest over his button-down Sunday shirt, “and because they need me here because I know where everything is. I’ve got a key to every part of the building.”

In May and early June, 20-plus inches of rain fell in parts of Oklahoma, causing widespread damage in and near the state’s second-largest city.

Weeks of flooding, tornadoes and storms left six people dead, 118 injured and hundreds of homes destroyed in the Sooner state, according to state emergency management officials.

The Red Cross shelter at the Crosstown church was the first to open in Tulsa. At the height of the disaster, it housed close to 100 people a night.

Susan Robinson, 76, with her dog “Little Bit,” at the Crosstown shelter. RNS photo by Bobby Ross Jr.

As many evacuees received federal disaster assistance, that head count slowly shrank, but victims such as Susan Robinson, 76, who fled the Sandy Park Apartments with her 15-year-old Pomeranian, “Little Bit,” depended on the church for weeks.

“The people here have been so kind, so it feels like home,” said Robinson. “The Red Cross has been good, and the minister has been by every day.”

Sam Duvall, 43, and his wife, Alicia, had an hour to gather important papers and a few belongings when flooding forced them out of their residence. They stayed in a motel for about a week.

But they eventually ran out of money.

“These people are wonderful,” said Duvall, holding a Bible after attending the Crosstown church’s morning worship assembly. “You know, I’ve never stayed in a shelter before, and they’re great — the church and Red Cross both. I couldn’t ask for a better group of people.”

Just after 9 a.m. on a recent Sunday, a few shelter residents snoozed on cots scattered across the gymnasium floor. Others sat at tables, eating cereal and drinking coffee in plastic foam containers. A few smoked outside the church as members arrived for Bible class.

Before heading to the auditorium to preach, minister Robert Prater mingled with the increasingly familiar faces. He assured one man that it would be no problem for him to worship in shorts.

Prater said he makes it a point to be available for the flooding evacuees — to offer hugs and spiritual support.

“It’s almost like I have two congregations right now,” Prater said. “Because these people, they really do need pastoring. … I’m going to be there until the last one.”

Across the Midwest, 28 Red Cross and community shelters in five states have tended to hundreds of victims.

Many of those shelters are at houses of worship, such as Corinthian Baptist Church in Dayton, Ohio, and Evangel Temple Assembly of God in Fort Smith, Ark.

Here in Tulsa, the Crosstown church first opened its doors to strangers needing a place to eat, sleep and shower as thousands fled New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Minister Robert Prater, right, visits with J.D. Morgan at the Crosstown Church of Christ shelter. RNS photo by Bobby Ross Jr.

The urban congregation overlooking Interstate 244 had dedicated its new activity center a month before Katrina hit.

“Y’all got a big building out there, I understand,” a Red Cross official who called Hearrell said, as he recalls the 2005 conversation. “We’ve got a bunch of people coming in from New Orleans. Can we use the church as a shelter?”

Hearrell replied that he’d ask the church’s elders.

“The Red Cross needed the space, so we moved all of our stuff out and turned it over, I think, for 52 days, and they basically took over,” said former elder Tom Conklin, still a Crosstown member.

Since then, the church has opened the shelter after disasters ranging from apartment fires to tornadoes. “We’re the first place that opens up if they need a place for overnight stays,” Conklin said. “I think it’s the heart of this church.”

A big part of that heart, he stressed, is Hearrell.

Kenneth Hearrell, right, with Mark Guilds, an American Red Cross volunteer from Albany, N.Y. at Crosstown Church of Christ in Tulsa, Okla. RNS photo by Bobby Ross Jr.

“He’s a very simple man, and you might look at him and think, ‘What’s his worth in the kingdom?’” Conklin said. “But he’s had a huge impact on a lot of different people, just by being a hard worker and by being a big, positive impact.”

Hearrell stood at the door of the activity center one Sunday morning a few weeks ago, greeting shelter residents as well as church members arriving for worship. Since the facility opened, he has worked most days from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m.

“This is his church, so to have him here has been so helpful,” said Matthew Griffiths, a 25-year-old Tulsa waiter volunteering as the Red Cross shelter’s manager. “He’s been so great, taking all the towels (to the laundromat every afternoon) and making sure they’re clean for people that need to take showers.”

Hearrell lost Martha, his wife of 57 years, about seven years ago. The couple raised two daughters. He has eight grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren. They call him “Papa.”

“He’s a funny guy but has a great story and is truly an inspiration to many,” Prater said of the disaster deacon.

Besides overseeing the church’s response to storms, Hearrell jokes that he works with a different kind of disaster — the democratic process.

Two precincts vote at the Crosstown activity center, and he coordinates that process with election officials.

“So I’m a disaster man,” Hearrell said with a laugh.

(Bobby Ross Jr. writes for The Christian Chronicle, where this story first appeared. The original version of this story can be found here.)