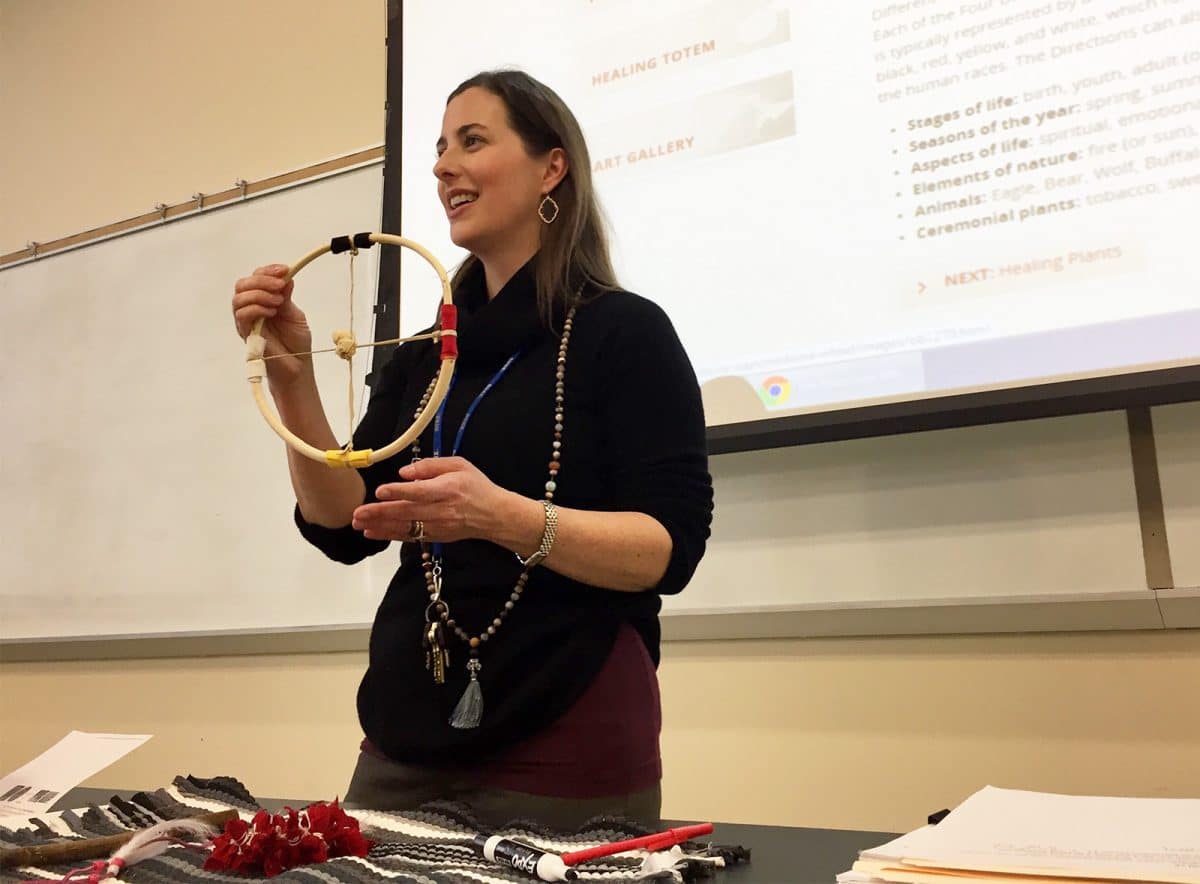

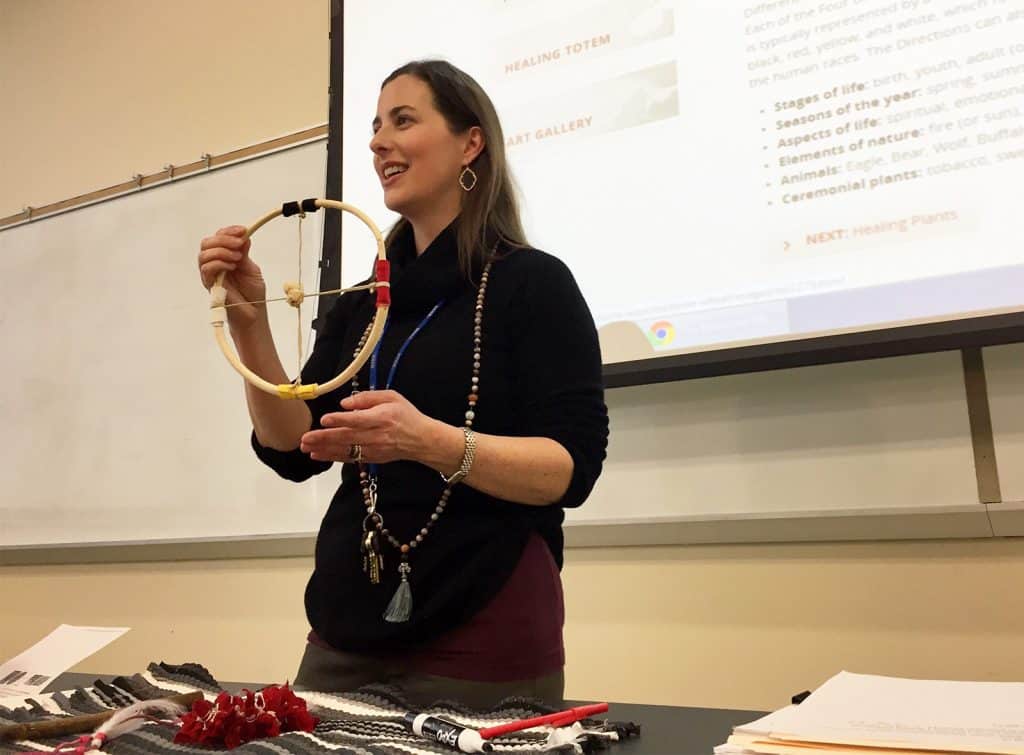

J. Dana Trent shows a medicine wheel in her World Religion class at Wake Technical Community College in Raleigh, North Carolina, on Jan. 30, 2020. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

RALEIGH, N.C. (RNS) — The students in J. Dana Trent’s World Religion class watched closely as she unwrapped several Native American objects – a medicine wheel, a cottonwood self-offering stick and a garland made up of Lakota prayer ties.

J. Dana Trent in 2017. Courtesy photo

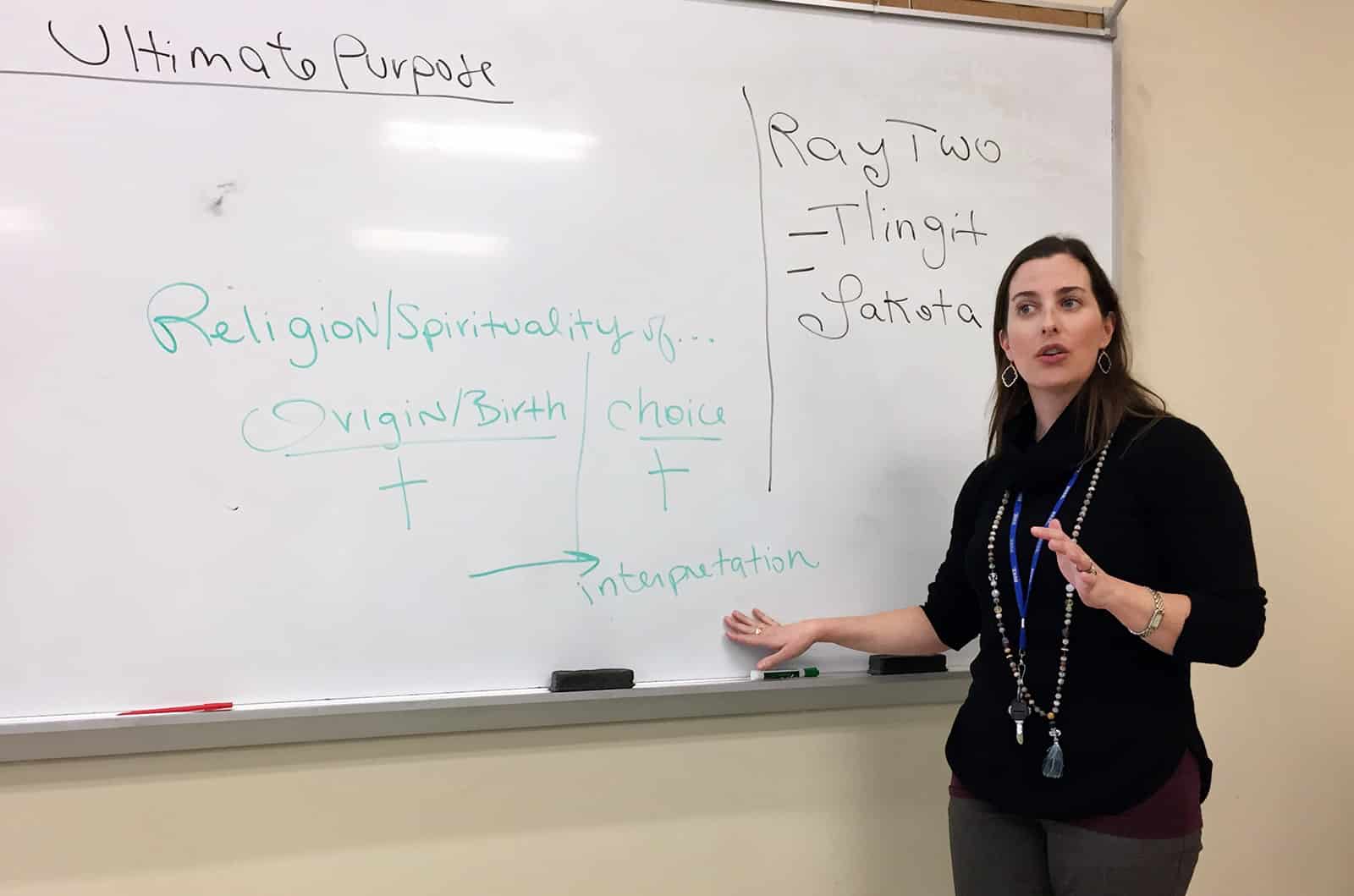

They listened intently as Trent explained the traditions rooted in the time-worn objects she showed them. But they became really animated when she invited them to a freewheeling discussion of how different faiths understand ultimate reality and how people who don’t identify with any one religion might make sense of death in their own lives.

“Based on what we learned in Chapter 2, how can the ancient wisdom of indigenous people help us think through today’s big questions of grief, death and loss?” she asked her students. “Is there any wisdom that transfers to us?”

This is a subject Trent, a 38-year-old writer, interfaith minister and instructor at Wake Technical Community College, returns to again and again in the classroom: How do you understand the meaning of life and death? And, more urgently, how do you grieve?

Many of the students have come to recognize — and appreciate — Trent’s pivot.

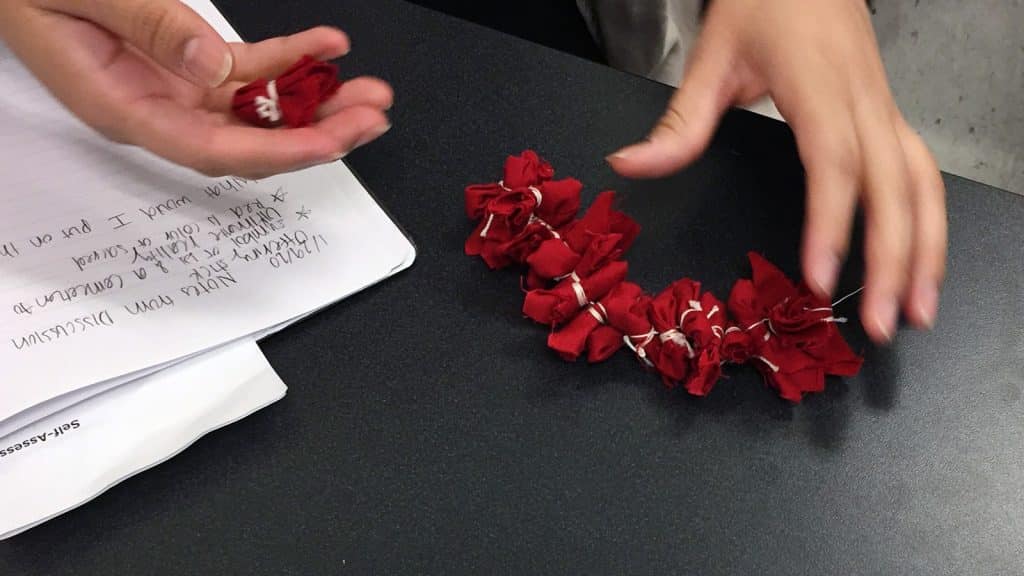

Each student in J. Dana Trent’s World Religions class was allowed to examine Native American prayer ties. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Krystal Rios, a student, told Trent and the class about a friend who died of an opioid overdose and how she and her friends grieved by sharing stories about her friend.

Another student whose friend died in a car crash, spoke of the rings her friend had worn and how she wears them now to keep the memory of that friendship alive.

Trent, who calls on her students by their first name, makes sure each one has an opportunity to say something — even if they haven’t raised their hand.

Unlike recent generations who, Trent said, went to extraordinary lengths to avoid open discussions of death, she is eager to reframe discussions of mortality for the post-Millennial generation. By doing so, she hopes to show them that looking death in the eye can create powerful lessons on how to live.

“Dessert First: Preparing for Death While Savoring Life” by J. Dana Trent. Courtesy image

Her latest book, Dessert First: Preparing for Death While Savoring Life, describes the year Trent spent as a chaplain at the University of North Carolina Hospitals’ intensive care unit and how she used what she learned there to care for her ailing mother a few years later.

In the ICU, Trent comforted family and loved ones of about 200 people who died over the course of the year, earning her the nickname “the death chaplain.”

A few years later, her mother, with whom she lived most of her life, fell ill and died.

Judith Wade Trent believed in dessert first, because “life is uncertain.” Her death gave Trent what she writes is an “unquenchable hunger for life and meaning-making.”

Trent’s fascination with death is part of a growing “death positive movement,” a term that borrows from the earlier “sex positive” movement. Its adherents believe in wresting control of death from the funeral industry and breaking the silence around death through frank discussions.

Caitlin Doughty, a mortician, is one of its most prominent popularizers. She created the Order of the Good Death and wrote a best-seller, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory.

But the movement is far larger. It includes “Death Cafe,” gatherings now in multiple countries where people talk about death, as well as people committed to home funerals and green or natural burial. There’s also a new class of caregivers who support people in the throes of death, sometimes called “death doulas.”

Trent, who was ordained a Baptist, graduated from Duke Divinity School and married a former Hindu monk, is more interested in grieving practices and what meaning people can take away from them. Her previous books were about interfaith marriage, Sabbath rest and Christian meditation.

“There are very few people given the honor and privilege of sitting at people’s bedsides,” she said. “I would feel very guilty of not being of service by sharing what they shared with me.”

She speaks frequently to church groups, which in recent years have begun hosting workshops on “dying well” featuring lawyers and health care professionals that offer guidance on drafting a will, signing advanced health care directives, and planning a funeral or memorial service.

J. Dana Trent keeps a photo of her mother taped to a shelf in her office at Wake Technical Community College in Raleigh, North Carolina. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Trent helps facilitate discussions about a good death. She recounts her own mother’s “red notebook” in which she wrote down not just her desire to be cremated, but also the hymns she wanted sung and the themes she wanted said in her eulogy.

“She (Trent) has a gift for presence,” said Sally Bates, a retired chaplain at Duke Divinity School. “She knows how to be in the present moment and how not to manipulate that moment, change it or get out of it. She’s unbelievably sensitive about moments of great intensity.”

Trent belongs to a liberal Baptist church in Chapel Hill but rarely attends these days. And, she’s well aware she’s not alone. Religious congregations and religious rituals are not always the go-to sources of comfort and care for the grieving and for those considering their own mortality.

“There used to be a built-in pressure release valve where people gathered to both grieve, mourn and bereave,” Trent said. “There’s no communal space for that built into society.”

Filling the gap in recent years have been an explosion of books and podcasts about sickness and death — from Kate Bowler’s Everything Happens for a Reason, to Nora McInerny’s popular podcast, “Terrible, Thanks for Asking.”

But many of these resources, Trent has found, draw educated, middle aged and middle class whites — sometimes referred to as the NPR crowd.

Trent wants to explore how younger people, like her community college students, are dealing with the issue.

Gen Z is experiencing a surge of grief. Suicide is now the second-leading cause of death among young people, surpassed only by accidents, according to the Centers for Disease Control. The nationwide opioid epidemic has led to a sharp increase in the death rate for overdoses by teens and young adults.

J. Dana Trent, right, speaks with a student after class at Wake Technical Community College in Raleigh, North Carolina. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

“Every semester,” Trent said, “someone comes up and says, ‘I’m not doing well today. I’m tearful. I’ve had a bad week because X attempted suicide’ — insert: ‘brother,’ ‘boyfriend,’ ‘girlfriend.’ Or my best friend committed suicide. I’m going to the funeral I won’t be in class on Friday.”

In the age of smartphones and social media, fewer young people have in-person social interactions and many prefer texting to actual conversation.

Which is why she has made the coping techniques of Gen Z and younger Millennials’ in such situations of loss and grief a teaching goal this year.

Her students appear to appreciate it.

Rios, like many other students, was reared in a Christian home but quit going to church when she realized the one she had been attending did not affirm LGBT people.

“The topic of death isn’t something people want to talk about, but in the class we talk about it like it’s a normal conversation, which it kind of is,” said Rios, 19.

In last week’s class, Trent offered the students an opportunity to open up about legendary NBA champion Kobe Bryant’s recent death in a fiery helicopter crash and their feelings in the days that followed. Some found solace in the vigils, moments of silence and the way Bryant’s jerseys — with the numbers 8 and 24 that he wore with the Lakers — lifted them and his memory. Others raised questions about such a quick and public mourning, especially after social media alerted people to his death before family members of those aboard the helicopter had been notified.

J. Dana Trent teaches a World Religion class at Wake Technical Community College in Raleigh, North Carolina. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Some students acknowledged that talking about death is scary and sometimes disconcerting.

“As a Christian, sometimes I struggle with my beliefs,” said Brenda Pianigiani, 23, a new immigrant from Italy. Pianigiani’s grandfather recently died, and she worries whether he’s in heaven since he was not a Christian.

But in a strange way, Pianigiani also finds the class discussions freeing.

“I want to be able to be more open and understanding when it comes to the beliefs of other people who don’t share it with me,” she said.

That’s exactly the point of the class, said Trent. She wants her students to try to understand other people’s beliefs so that they might have more tools and ideas to draw from when facing grief, the most important of which, she believes, is empathy.

She then switches back to the Lakota self-offering stick upon which Native peoples tie various objects of significance along their life’s journey: a baby bracelet, a lock of hair, a piece of jewelry.

“When you come in on Tuesday,” she instructed, “think of what you would tie on a self-offering stick particularly as it pertains to death, grief and loss.”