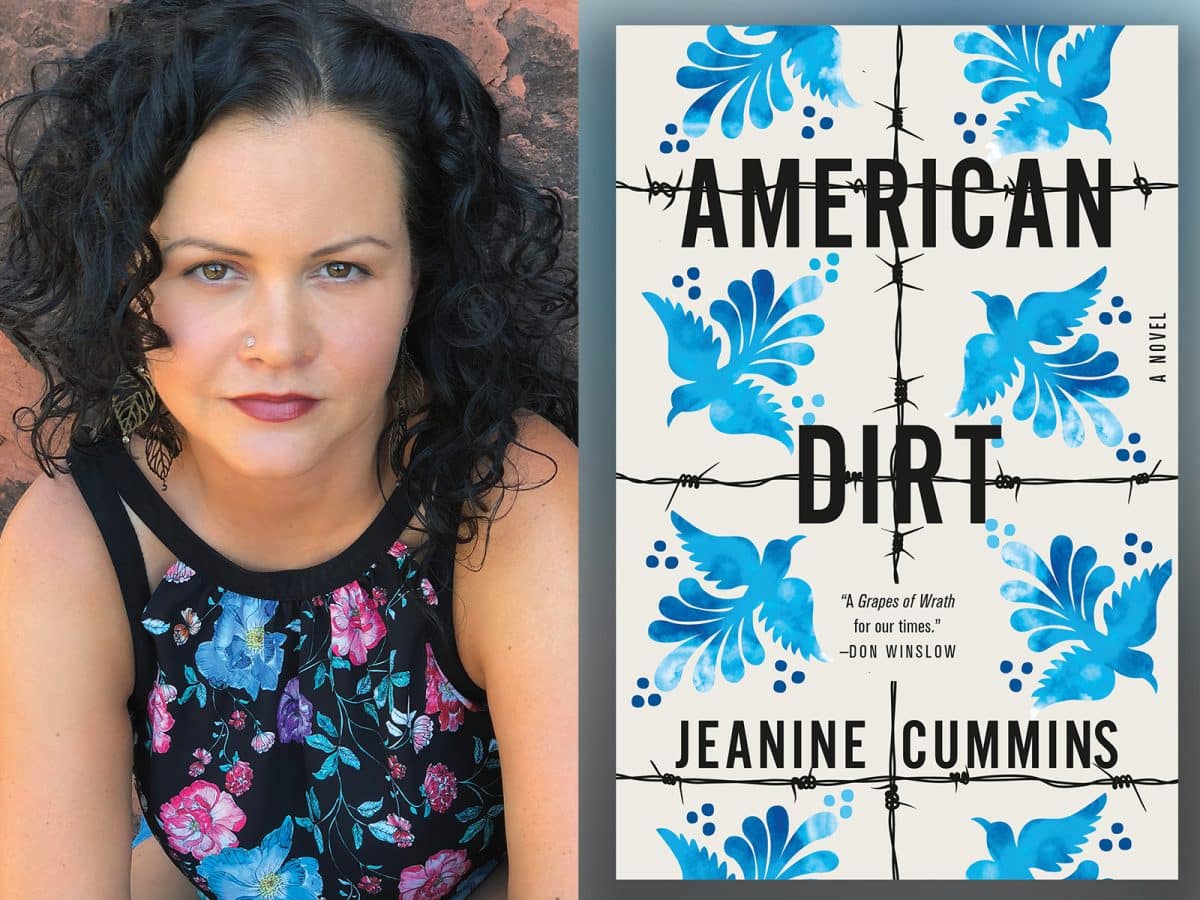

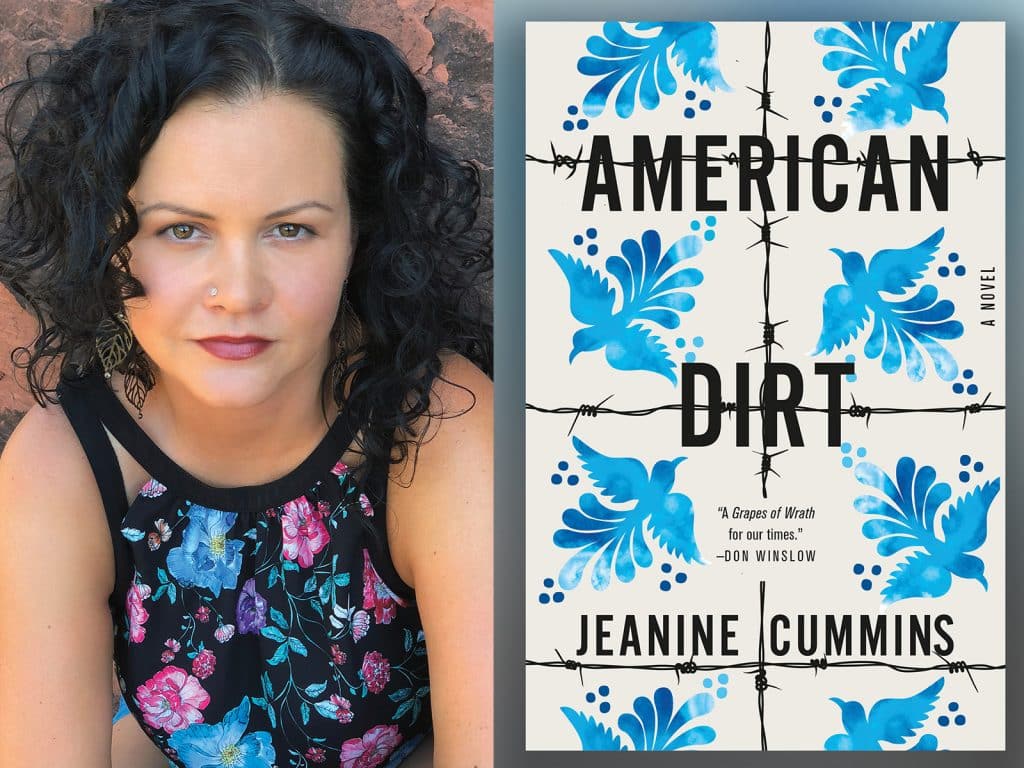

Author Jeanine Cummins and her controversial book “American Dirt.” Courtesy images

(RNS) — The book tour of the bestselling novel “American Dirt,” the story of a mother-son duo fleeing Mexico for the United States, has been canceled by Flatiron, which cited “safety concerns” regarding its author, Jeanine Cummins.

Although the book received florid initial hype — including multiple New York Times reviews and a spot on the Oprah’s Book Club pick list, Cummins soon came under fire from other writers and activists for misrepresenting her heritage (Cummins has a Puerto Rican grandmother but publicly identified as white as early as 2016) and appropriating the Latinx cultural experience.

To her critics, Cummins was the worst kind of fraud: taking the very real, vital story of the migrant crisis and whitewashing it for profit. (It didn’t help that Cummins and the “American Dirt” promotional team were prone to tone-deaf publicity stunts like featuring barbed-wire centerpieces at dinners in honor of the book.)

Cummins is far from the first high-profile author to stoke the ire of readers. This month alone, a Latinx writer, Wendy C. Ortiz, called out Kate Elizabeth Russell, the author of the novel “My Dark Vanessa,” a story of a student-teacher affair that bore numerous resemblances to Ortiz’s own memoir, “Excavation.” While Ortiz stopped short of accusing Russell of outright plagiarism, she heavily implied that Russell, who is white, was able to get a major fiction deal in part because of the implicit racism in the publishing industry.

And late last year, an even more significant figure, “Harry Potter” author J.K. Rowling, became the subject of intense fan scrutiny after tweeting sympathetically about the controversial case of Maya Forstater. Forstater had become the subject of a media firestorm in the U.K. when she launched a lawsuit to counter her dismissal from a think tank after she tweeted numerous statements critical of transgender people and implied she didn’t think trans women were “really” women.

J.K. Rowling attends the 2019 Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Ripple of Hope Awards at the New York Hilton Midtown on Thursday, Dec. 12, 2019, in New York. (Photo by Greg Allen/Invision/AP)

For Rowling’s fans, many of whom saw in the “Harry Potter” messages of resistance and inclusion a kind of model for millennial progressivism (as late as 2016 and 2017, signs for “Dumbledore’s Army” were regular fixtures at anti-Trump rallies and Women’s Marches), her perceived transphobia was a major betrayal.

Cummins’ fall from grace was much swifter than Rowling’s, and — because “American Dirt” hadn’t exactly become a cultural juggernaut the way “Harry Potter” has been — a perhaps less complicated one. But both stories can tell us something about the way in which shared media properties, in an era when we have fewer and fewer stories held in common, take on an outsized moral role in the way we think about broader ideas.

The Rowling case raises questions of who is entitled to tell a story, or, in Rowling’s case, who has control over a fictional world, and of its narrative. The progressive, inclusive world “Harry Potter” seemed to promise its readers appeared to have been undercut by its very creator — even as fans sought to re-appropriate and reclaim the world of Hogwarts as a place for trans-inclusive, progressive, values. It’s telling that many of Rowling’s former fans see themselves as ongoing participants, through fandom and fan fiction, in the Potterverse.

It is, of course, no coincidence that both fan backlashes arose specifically on the internet.

After all, it has been the proliferation not merely of internet technology but also of internet literary culture — the inherent suspicion of the top-down, authoritarian notion of storytelling, the idea that authors have a de facto right to own and convey their chosen narratives — that the freewheeling internet fan culture has fostered.

In the age of fan fiction, the age of memes, the age of mashups and YouTube compilations, we no longer take for granted that there is a single, fixed narrative — one that belongs to the author, by virtue of him or her having invented it.

Rather, stories are now seen as collective property: There may be stories, even like the one Cummins invented, that do not belong to the author who has written them, because of their subject matter or perspective. There may, too, be stories like Rowling’s: textual worlds that are seen as the property of fans, first and foremost, and only secondarily the property of their progenitor.

Internet storytelling culture demands not passive literary consumers, but active participants — allowed, even entitled, to weigh in, to reimagine, to reinvent and to reclaim.

This is a religious phenomenon as much as it is a literary one.

In an era when millennials in particular are increasingly suspicious of organized religion, of doctrine and dogma and rules, and drawn to models of faith that prioritize personal responses to a story, narrative or deity, our personal faith systems and approach to narratives are deeply intertwined.

Religious identity, for more and more millennials, rests on an intuitional rather than authoritative model.

The freedom — narrative and otherwise — that the internet provides makes the idea of simply adhering to a doctrine, or to a particular clerical figure’s view of it, less normative.

As former “700 Club” producer Terry Heaton told me in an interview back in 2017, contrasting the contemporary internet landscape with his experience at the Christian Broadcasting Network: “The web is a three-way communication street. It’s not one-way. The network is top to bottom, but (the web) is bottom to bottom. It doesn’t need any hierarchical approval.”

Twitter-based movements like #ChurchToo and #exvangelical, for example, allow disaffected and disillusioned evangelicals (and former evangelicals) to speak openly and critically of church culture, making space for progressive and marginalized experiences within religious discourse.

How we see our own approach, assent and assimilation of texts — be they sacred or secular — determines in turn how we see our approach to the foundational stories that govern our own lives. And, for Rowling and Cummins as much as the authors of the four Gospels, the authoritative narrator has been displaced.

We are in an age of responsive readers, now.