As state and local officials across the country ban churches — like other groups — from holding gatherings of more than 10 people, some politicians in Kansas have invoked Easter in a partisan fight over gubernatorial power. With church services already sparking numerous coronavirus hotspots across the country, many medical professionals and governmental officials fear in-person services on Easter could prove deadly.

As of April 10, nearly 1.7 million people globally have been infected with the COVID-19 respiratory disease caused by coronavirus, and more than 102,000 have died. In the U.S., the country with the highest number of infected persons, more than 495,000 have tested positive and more than 18,000 have died.

Although more than 90 percent of churches across the country have suspended in-person services for weeks, the importance of Easter Sunday raises temptations for some to reopen. Several states have included religious exemptions from stay-at-home orders that would allow churches to gather in-person for large services, such as in Connecticut, Florida, Michigan, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and West Virginia.

However, most churches remain closed despite exemptions because of the danger of mass gatherings. Large outbreaks have been traced to churches in Arkansas, California, Georgia, Illinois, Washington, and elsewhere.

On Monday (April 6), Kansas reported three clusters of the virus were linked to churches in Kansas City, Kansas: Rising Star Baptist Church, Power Realm Church of God in Christ, and a ministers’ conference at Miracle Temple Church of God in Christ.

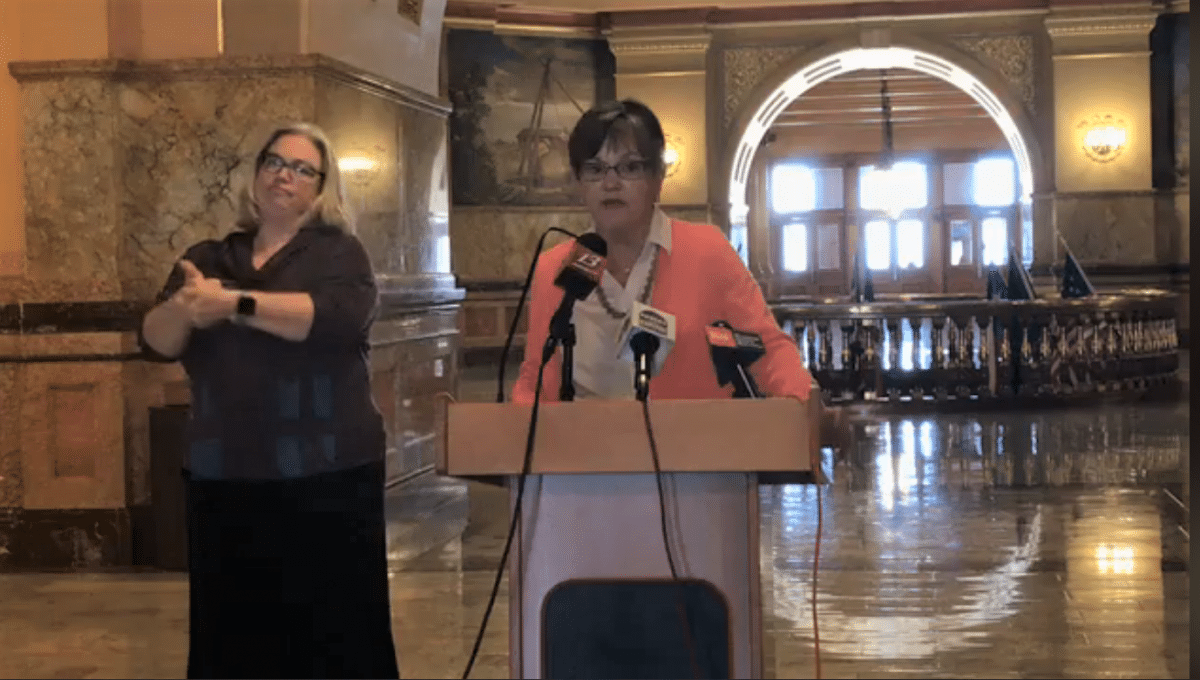

Screengrab of Kansas Governor Laura Kelly announcing on April 7 her order removing the religious exemption to the state’s ban on mass gatherings.

The next day, Kansas Governor Laura Kelly, who is Catholic, responded to the news of the church-related virus hotspots by removing the religious exemption in her earlier stay-at-home order. After coronavirus cases in the state topped 200, Kelly issued a statewide stay-at-home order on March 28. But that order exempted religious groups from the ban on mass gatherings of more than 10 people.

After the news of the three church-related clusters and after the state’s cases topped 900, Kelly issued a new stay-at-home order on April 7 that removed the religious exemption. She admitted that issuing the order just days before Easter “was a difficult decision and could not come at a more disappointing time.” But she insisted it was critical and part of the religious teaching to “love our neighbors as ourselves.”

“Holy Week is underway. And with Kansas rapidly approaching its projected ‘peak’ infection rate in the coming weeks, the risk for a spike in COVID-19 cases through additional church gatherings is especially dangerous,” Kelly explained.

Kelly added that her order did not ban religious services, but merely limited the size of the gatherings and how close people should stand — just like the rules for other gatherings in the state. Her order quickly sparked backlash from state Republicans. Elected as a Democrat in 2018 after eight years of Republicans holding that office, she’s faced a legislature where Republicans outnumber Democrats by more than 2-1 in both chambers. Although previous Republican governors had broad authority for executive actions during emergencies, as coronavirus grew in the state, lawmakers voted to limit Kelly’s emergency powers.

Kansas’s Attorney General Derek Schmidt, a Republican, on Wednesday (April 8) told police across the state not to enforce Kelly’s order on any religious gathering. Later that same day, the state’s Legislative Coordinating Council — which is made up of seven leaders from the state’s House and Senate — voted on a 5-2 along party lines to revoke Kelly’s order.

Republican State Senate President Susan Wagle, a Catholic running for U.S. Senate this year, criticized Kelly’s order as “a violation of their constitutional rights to have the government tell them that they cannot participate in a church service.”

Republican State House Speaker Ron Ryckman, a Nazarene, argued Kelly’s order “limits the free exercise of religion.” He also said the state should trust clergy to make their own decisions and protect their own congregations, adding, “No evidence has been shown to indicated that faith leaders are violating that trust.”

Kelly denounced the Council’s move as “shockingly irresponsible” and filed a court challenge to the action. She added, “There are real life consequences to the partisan games Republicans played today.”

The state’s Supreme Court will hear the case Saturday morning, perhaps to issue a ruling later that day before Easter. Some local orders in Kansas that do not exempt houses of worship from mass gathering bans are still in place.

Despite the claims of Kansas Republican leaders, governors in at least 18 states have closed churches during the coronavirus outbreak, as did many states — including Kansas — during the 1918 influenza pandemic. And legal challenges to such orders in other states have failed. A judge in New Hampshire ruled March 20 against plaintiffs — including a Baptist Sunday School teacher — who challenged the lack of religious exemption in Republican Governor Chris Sununu’s order banning mass gatherings. On April 9, a Virginia judge similarly refused to issue an injunction on Democratic Governor Ralph Northam’s ban on mass gatherings.

Screengrab of Missouri Governor Mike Parson talking about faith and coronavirus on Good Friday (April 10).

In neighboring Missouri, Republican Governor Mike Parson, a Southern Baptist, has also evolved on this issue. But he hasn’t faced pushback from his fellow Republicans who control the statehouse. Like Kelly, Parson initially offered a religious exemption. He said on March 20 that his order banning mass gatherings of more than 10 people “will not apply to religious services.”

However, when responding to a question by Word&Way during his daily briefing on April 2, he changed the stance to declare that “churches fall in the same requirements as people under the order.” He codified that rule the next day in his new stay-at-home order that specifically noted that “places of worship” must adhere to the social gathering limits and practice social distancing. He did, however, allow a narrow exemption to permit individuals to travel to or from their house of worship, which would allow music and tech volunteers to leave home to help record an online service (provided that 10 or fewer people are in the sanctuary and they practice social distancing).

On April 9, Parson reiterated that churches “have to abide by the order” when asked about the upcoming Easter Sunday. He praised churches for creative ways of worshiping — like online worship or drive-in services — but then stressed again, “You have to abide by the order; you don’t get an exception for that.”

The next day, on Good Friday, Parson again noted that his ban would prevent churches from meeting on Easter.

“Some of the hardest decisions that I’ve had to make since being governor have impacted the people of faith: where they can gather, where they can worship during this time of crisis,” he said. “They are decisions no governor ever wants to make. And I hope I never face them again.”