As most churches across the country shifted to online worship services due to the coronavirus pandemic, a few tried a more low-tech way of worshiping without gathering together in a confined space: drive-in services. However, those drive-in worship services sparked church-state conflicts during Holy Week as some governmental officials view the drive-in services as still covered by bans on mass gatherings. But unlike the unsuccessful legal challenges so far by churches seeking to hold worship services in their sanctuaries, the drive-in services have found some judicial support.

As of April 13, more than 1.9 million people globally have been infected with the COVID-19 respiratory disease caused by coronavirus, and more than 119,000 have died. In the U.S., the country with the highest number of infected persons, more than 580,000 have tested positive and more than 23,000 have died.

With churches linked to coronavirus hotspots across the country, many state and local officials have refused to offer religious exemptions to bans on mass gatherings. And even in places with those exemptions, more than 90 percent of churches have shifted to an alternative way of worshiping.

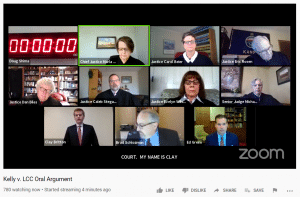

Screengrab of Kansas Supreme Court hearing oral arguments via Zoom on April 11.

On Saturday (April 11), the Kansas Supreme Court held an emergency oral arguments session over Zoom after a Republican-led seven-member committee of state lawmakers revoked the Democratic governor’s order removing the state’s religious exemption from the ban on gatherings of more than 10 people. Later that evening — just hours before Easter Sunday — the Court ruled the lawmakers didn’t properly act, thus reinstating the ban on large religious services.

Legal challenges to state bans on mass gatherings in churches have also failed in New Hampshire and Virginia. But each of those cases involved in-person services held in sanctuaries.

As churches started suspending in-person services last month, some decided to try drive-in worship instead of an online format. Many such congregations are in rural communities with less internet capacity and with older members not as proficient with online platforms. With this format, people arrive in the church’s parking lot but are supposed to park at least six feet away and stay in their cars while the preacher leads the service with amplification or on a shortwave radio signal.

Initially touted by religious groups and publications as a creative way of worshiping amid coronavirus restrictions, some local officials have since argued such services shouldn’t be allowed. Yet, unlike orders banning religious gatherings along with other mass groups, the actions against drive-in services have often appeared targeted only at religious groups.

In Greenville, Mississippi, local officials say their ban on in-person services includes drive-in services. Two Baptist churches faced police officers when they held such services during Holy Week.

“We were abiding by the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] guidelines,” said Charles Hamilton, pastor of the King James Baptist Church in Greenville, after police arrived during a Maundy Thursday service. “Members of the church were inside their cars, had their windows up, and I was preaching the word of God. So, no one was outside, and also we had cars at a distance. So, legally we weren’t doing anything wrong.”

After Greenville police disrupted a service on the Wednesday of Holy Week, Temple Baptist Church sued the city on Good Friday. Congregants at both churches who refused to leave the drive-in services reportedly received $500 tickets for each person in a car.

The city’s mayor, Erick Simmons, defended the ban by arguing that people might get out to use the bathroom, which could be a health risk. Simmons is a Baptist.

Other places banning drive-in worship services include a 10-county area in south central Georgia (south and east of Macon), and Riverside County in southern California (though it allowed an exception for Easter weekend). Democratic Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak, a Catholic, issued a stay-at-home order on the Wednesday of Holy Week that specifically banned any church gatherings — including drive-in services — that include more than 10 people. Baptist churches were among those who criticized the ban on drive-in services.

Officials in San Bernardino County in southern California reversed course after initially announcing on the Tuesday of Holy Week they would ban drive-in services. After receiving complaints from some local religious leaders, county officials the next day overruled the decision by the public health officer, but stressed precautions for such services must include everyone stays in their own car.

The police department in Wilmington, North Carolina, similarly announced on Maundy Thursday that drive-in churches services would not be allowed — before changing the announcement later that day. The updated Facebook post noted they had “been in discussion with the Governor’s office” and learned Democratic Governor Roy Cooper, a lay leader in his Presbyterian church, did not believe drive-in services were banned by his updated statewide order issued that day, which noted religious groups weren’t exempt from the ban on gatherings or more than 10 people.

“It is the Governor’s interpretation of his own order that ‘drive-in’ worship services should be allowed if sufficient safety precautions are met. As a result, such services will not be considered a violation,” the police department wrote. “Health department officials have established the following recommendations: all vehicles maintain a distance of at least six feet from any other vehicle on all sides, all persons stay in their vehicles, and only immediate family or members of the same household occupy the same vehicle. It is further advised that services last no more than one hour in order to prevent people from needing to leave their vehicles for any reason, including going to the restroom.

The department added, however, that local health officials advised against drive-in services, and thus the department encouraged people to instead hold virtual services.

That same day, Wisconsin Democratic Governor Tony Evers issued a statement clarifying that while churches were included in his ban on in-person gatherings of more than 10 people, that did not ban drive-in services. Some local health and governmental officials had been notifying churches ahead of Easter that drive-in services were not allowed. Among the “creative ways” Evers listed for churches to meet under the restrictions, he included “parking lot services with congregants staying in cars, avoiding person-to-person contact.” Evers rebuffed calls from state Republican lawmakers to allow large in-person services for Easter.

Tim Schultz preaches March 22 during a drive-in church service at Little Brushy Baptist Church in Wappapello, Missouri. Schultz wrote about that experience for Word&Way.

The most significant conflict over drive-in services last week erupted in Louisville, Kentucky, after the city’s mayor, Democrat Greg Fischer, banned drive-in services on the Tuesday of Holy Week. He argued, “It’s not really practical or safe to accommodate drive-up services taking place in our community.”

One of at least six churches planning to hold such a service sued on Good Friday, and other politicians spoke out against the ban. Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear, a Democrat, and Attorney General Daniel Cameron, a Republican, both said drive-in churches weren’t banned by the state’s orders. Beshear, whose grandfather and great-grandfather were Baptist preachers, had previously urged churches to not hold in-person services. Cameron said he sees “no problem” with drive-in services “as long as religious groups and worshippers are complying with current Centers for Disease Control recommendations for social distancing.”

“Religious organizations should not be treated any differently than other entities that are simultaneously conducting drive-through organizations, while also abiding by social distancing policies,” he added. “As long as Kentuckians are permitted to drive through liquor stores, restaurants and other businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic, the law requires that they must also be allowed to participate in drive-in church services, consistent with existing policies to stop the spread of COVID-19.”

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, a Republican from Kentucky, also spoke out to support drive-in churches. While McConnell said he didn’t support churches holding large in-person gatherings, he didn’t think drive-in religious services should be singled out for “disfavored treatment.”

On April 11, U.S. District Judge Justin Walker issued a temporary restraining order blocking the mayor from banning drive-in churches, thus allowing such services for Easter the next day. Walker called the mayor’s position “stunning,” unconstitutional, and “beyond all reason.” Walker, who President Donald Trump recently nominated for the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, also compared it to something found in “the pages of a dystopian novel or perhaps the pages of The Onion.” Although the ruling allowed drive-in services for Easter, it might be challenged before upcoming Sundays.

Al Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, praised the judge’s ruling. While Mohler had previously urged churches to follow “generally applicable shelter-in-place orders” that ban in-person mass gatherings, he argued the targeting of drive-in services “goes far beyond rational policy generally applied.” He said the latter creates an “egregious” violation of religious liberty since religious gatherings are “singled out” with “a specific targeting.”

“If you can have legal drive-through liquor, it is hard to argue that you can’t have legal drive-in worship services,” Mohler added.

The issue of bans on drive-in and other church services might garner more political attention this week. On Saturday — the same day as the court rulings in Kentucky and Kansas — a Department of Justice spokesperson tweeted that the DOJ would act soon against local officials who single out religious organizations in government regulations during this emergency time.