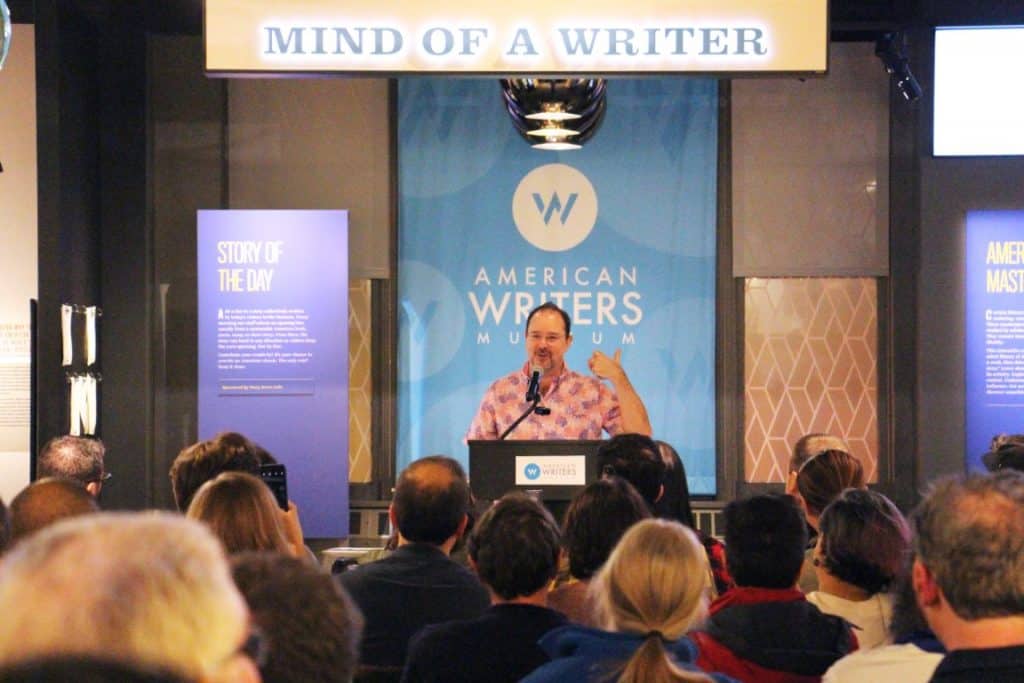

Science fiction author John Scalzi speaks about his new book “The Consuming Fire” on Oct. 22, 2018, at the American Writers Museum in Chicago. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

(RNS) — John Scalzi gave up on God at an early age.

The best-selling science fiction author was baptized as a baby, went to Sunday school with his churchgoing aunt when he was very young and enjoyed some of the stories he read in the Bible she had given him.

By eight, however, he had pretty much decided faith was not for him.

But the Bible stories, like Samson and Delilah, stuck with him. He liked the action in the story and the image of Philistines lying in wait to ambush the biblical strongman.

Author John Scalzi in 2019. Courtesy photo

“I also remember thinking Samson must not have been very smart, because he kept telling Delilah ways to weaken him, and then didn’t make the connection when she would tie him up and then suddenly pow, Philistines everywhere,” he told readers on his popular blog, The Whatever, in a post about his childhood experience with religion. “After the first couple of times, you would think he would have figured it out. But clearly, when it came to Delilah, it wasn’t his brain Samson was thinking with.”

While Scalzi identifies as an agnostic, a mix of action, sly humor and religion has become a mainstay of his popular sci-fi novels, from “Old Man’s War” (a fusion of space opera, romance and reincarnation) and the “Ghost Brigades” (which explores predestination versus free will in clones) to “The Dispatcher” (a short story exploring the downside of resurrection) and “The Collapsing Empire,” a trilogy in which a reluctant Messiah figure tries to save the universe.

Scalzi has a simple explanation for why his stories feature religion.

They have human beings in them, he said. And he believes human beings are inherently religious — their brains evolved to find patterns and meaning in a chaotic world. Besides, religion has shaped human society for millennia, sometimes for good and sometimes for ill, and that will likely continue.

“As we move forward in the future, I don’t think that religion and spirituality are going to disappear,” he told RNS in a phone interview from his home in rural Ohio.

Not surprisingly, his latest book, “ The Last Emperox,” set to release on April 14, is filled with religion. One of the main characters, Cardenia Wu, is both a political figure and the head of an actual church who uses both politics and religious visions to promote her goals. And church bureaucracy —inspired in part by the United Methodist Church’s recent conflicts — plays a key role in the plot.

And of course, there’s plenty of action.

“The Last Emperox” and author John Scalzi. Courtesy images

“The Last Emperox,” the final book in The Interdependency trilogy, is a page-turning romp of a story about the cost of saving the world in the face of an apocalypse and the sacrifice involved when a normal human being is asked to become a messiah.

Being a fictional messiah is not easy or simple. And saving the world is kind of a hassle.

“It’s not that you become the messiah and all your problems go away,” said Scalzi. “No. You literally take on all the problems of the world, as messiahs do.”

The book features a far-flung, futuristic space empire on the brink of a cataclysm. Known as the Interdependency, the empire was built to take advantage of the Flow, a set of fictional currents in space that allow for faster-than-light travel. When the Flow begins to collapse, some characters, including Wu, who is also the ruler, or “Emperox,” of the Interdependency, try to save as many people as they can.

Others use the collapse to gain political power, make money or save their own skins. Like any good apocalyptic tale, “The Last Emperox” reveals what really matters. Can everyone be saved? Or should some be sacrificed so the economy and the system can keep rolling?

Those questions are familiar to Americans during the coronavirus pandemic, said Scalzi, who wrote an earlier novel about the aftermath of a major pandemic. The characters in “The Last Emperox” have competing views on who should be saved and who is expendable — and on how to save the Interdependency’s economy, even if it costs people’s lives.

Those debates parallel recent conversations in the U.S. about whether older Americans should be willing to die of the coronavirus in order to get the country back to work and what kinds of patients should be given priority in the case of a shortage of hospital ventilators.

“We are discovering in real life, as the people are discovering in the books, who and what everybody thinks is important,” Scalzi said.

An apocalypse may reveal the dark side of some people, she said. But it can also inspire others to do the right thing because i

Scalzi’s recent trilogy of books does what all good tales of the apocalypse do, said Kelly J. Baker, a religion scholar and author of “ The Zombies Are Coming! The Realities of the Zombie Apocalypse in American Culture.”

The word apocalypse means ‘unveiling’ or revealing, said Baker. And an apocalyptic tale “reveals what matters to people and what is most sacred.”

She said people in a cataclysm often think they are doing the right thing — even when their decisions have detrimental outcomes for other people. And they justify their actions as being for the greater good.

“There are folks who think they are making the hard decisions, that they are on the side of the righteous — often those are terrible decisions,” she said.

An apocalypse may reveal the dark side of some people, she said. But it can also inspire others to do the right thing because it needs to be done. People who would otherwise be selfish realize they have to pitch in and help when the world is falling apart. That’s exactly what happens to Kiva Lagos, one of the key players in “The Last Emperox.” She is, Scalzi has admitted, one of the characters he most enjoyed writing.

Lagos is enthusiastically profane, relentlessly ambitious and funny as hell.

In the first book of the series, she shamelessly exploits refugees, charging millions for passage off of a war-torn planet. In the last book, she decides to become a better person and to help other people do the right thing — whether they like it or not.

In the real world, he said, morality is like that. Most people are selfish, he said. Few of us are altruistic by nature.

“If we require everyone to be a perfect moral actor, then we’re not going to get a whole lot of anything done,” he said.

But we can act in moral ways. And our actions change us, Scalzi said.

“It’s OK to hate being moral in some sort of way. It is OK to recognize that it’s work and that it’s exasperating. And that if you were left to your own devices in a world that didn’t require you to be a moral actor, maybe you wouldn’t be,” he said. “But in a world that does require you to be a moral actor, you just kind of go, ‘fine’ and, and you do it.”

Scalzi said he doesn’t want to hit people over the head with the religious or philosophical ideas in his books. As a commercial science fiction writer, he said his job is to deliver an enjoyable story for his fans. As long as he does that, he can weave in these other themes.

“There is this straight-ahead, epic space opera story going on where you have royalty and commercial interests and assassinations and all that sort of stuff, and you can just flip the pages,” he said. “But even after the book is done, you can still be thinking about (these bigger questions). You don’t have to — but if you want to, it is there.”