As churches across the country avoid in-person worship services, a historian and sociologist of religion in American life sees parallels to a previous pandemic. John Schmalzbauer, professor and Blanche Gorman Strong Chair in Protestant Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at Missouri State University in Springfield, Missouri, draws encouragement from the fact churches survived the 1918 influenza pandemic as the coronavirus outbreak continues.

As of April 20, more than 2.4 million people globally have been infected with the COVID-19 respiratory disease caused by coronavirus, and more than 169,000 have died. In the U.S., the country with the highest number of infected persons, more than 780,000 have tested positive and more than 41,000 have died.

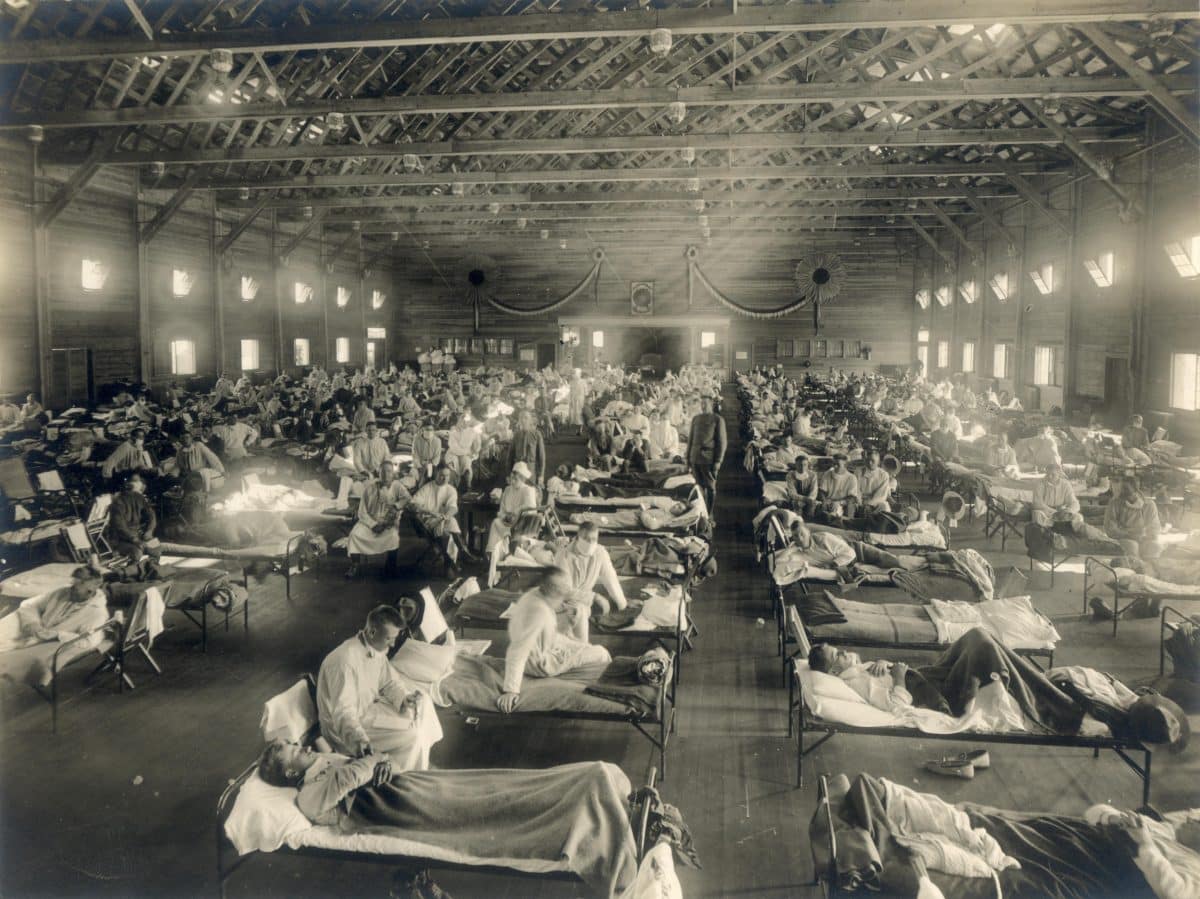

Emergency hospital during the 1918 influenza epidemic in Camp Funston, Kansas.

As churches started closing — many voluntarily, and others as local and state officials banned mass gatherings — Schmalzbauer looked at newspaper accounts from 1918 to compare how religious and government leaders reacted to the last major pandemic to hit the United States. He told Word&Way he sees many similarities with today’s situation.

Although often inaccurately called the “Spanish flu,” the 1918 flu pandemic likely instead started in France or Kansas. Troop movements for World War I helped spread the virus to other countries. It eventually infected an estimated 500 million people globally and killed between 17 and 50 million people. In the U.S., about 28 percent of the 105 million people were infected, and more than 500,000 died.

To stop the spread of the flu in 1918, many state and local officials banned large gatherings and ordered shutdowns of businesses and churches. Now called “social distancing,” such measures have been repeated during the coronavirus outbreak. And, like today, Schmalzbauer’s look at newspaper accounts suggests most churches agreed to suspend worship services to help save lives.

John Schmalzbauer

“You can look at newspapers from all over the United States that have been digitized, and quickly discover that they’re working through some of the same issues that we are working through today,” he explained. “Should we stop meeting together? How are we going to continue to have faith communities without being able to be in the same room as each other?”

But unlike today where churches are still gathering virtually on Zoom or Facebook Live, when churches suspended services in 1918, they really quit meeting together. Instead, as Schmalzbauer noted, “all they have is the home altar, as they called it.”

“There was a real Victorian emphasis on domesticity and religion in the home, and there were lots of devotional materials, books, and pamphlets and so forth that people used to kind of have piety in the home,” he added. “But there was no Zoom.”

Despite that, Schmalzbauer said “there doesn’t seem to be a lot of controversy” in the news reports, especially in rural parts of the region. There were some politicians and church leaders in St. Louis, Missouri, he added, that seemed “irritated” by the shutdown recommendations from the city’s health commissioner, Max Starkloff. Today, Starkloff is credited with saving tens of thousands of lives as St. Louis had one of the lowest death rates nationally from the flu outbreak.

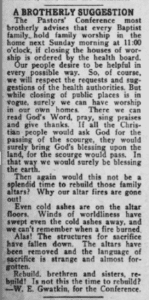

Snippet from Oct. 24, 1918, issue of Word&Way.

As part of his research, Schmalzbauer looked at how Word&Way covered the flu pandemic and recommendations that churches suspend gatherings. And he praised Word&Way for how it promoted health efforts rather than fighting official decrees.

“You read your publication, Word&Way, and they say that we’d like to give you some friendly advice that every family should get together at 11 a.m. Sunday mornings and have worship in your family unit. And so, they encourage people to do that,” he said. “The language from your publication was so polite and compliant and respectful of the public health people. They said, ‘Our people desire to be helpful in every possible way. So, of course, we will respect the requests and suggestions of the health authorities.’ And they said that we’re shutting down our churches, but let’s have worship in our homes.”

“And it’s touching to read the reports from the Baptist congregations that are in Word&Way,” he added. “They’re kind of somber and sad, you know, that we haven’t been able to meet. There have been a number of deaths here. And then there are other articles that talk about well, what’s the meaning of all this? How can we find meaning in our suffering? But there’s not this kind of resentment against public health officials. More or less, I think they were willing to comply.”

Laughing that his 11-year-old son asked him why he’s so obsessed with 1918, Schmalzbauer said it gives him “a certain amount of consolation that we made it through.” Noting that “tradition is the democracy of the dead,” he said it’s important to study history so we can learn from “those people who had to make those hard decisions in the past.”

“As a historian of American religion, sociologist of American religion, I guess I get some consolation that religious communities had to go through this before,” he added. “They were able to respond with kindness, and with a sense of duty and responsibility and the common good — and those things can help carry us through this time, too.”

NOTE: Hear more about this topic from Schmalzbauer in the latest episode of Word&Way’s award-winning podcast “Baptist Without An Adjective.”

NOTE: Hear more about this topic from Schmalzbauer in the latest episode of Word&Way’s award-winning podcast “Baptist Without An Adjective.”