Baptists and other advocates working to prevent predatory lending in Missouri are criticizing a legislative move that could undo local ordinances regulating payday loan institutions. Although many state legislatures across the country suspended sessions due to the coronavirus pandemic, Missouri’s lawmakers returned April 24 for weeks of work on issues unrelated to the heath crisis — ranging from legalization of brass knuckles to allowing feral hog killing.

After years of unsuccessful efforts to limit payday and car title loans at the state level — including efforts to cap interest to an annual rate of 36% — advocates focused more recently on creating local restrictions. Last November, voters in Liberty overwhelmingly passed a rule to limit the number of payday lending institutions to just one per 15,000 residents and to enact a $5,000 fee annually for such a lending license.

On May 4, the Springfield City Council unanimously voted to place a similar regulation on the August ballot, including the $5,000 annual fee. Both efforts came after advocacy by local Baptists and others.

However, those rules may now be in jeopardy. The same day as the council vote in Springfield, Rep. Curtis Trent, a Republican in Springfield, introduced an amendment to a growing Missouri Senate bill that advocates fear will undo their local predatory lending regulations. Senate Bill 599 originally focused on the amount of money the State Treasurer could invest in various places. But after missing a couple weeks of the session due to the outbreak, multiple lawmakers tacked amendments onto that and other bills in hopes of passing initiatives that had otherwise stalled out during the 2020 session that ends on May 15.

One of the amendments put on SB 599 came from Trent, which would prevent state and local officials from charging a fee to an installment loan lender that isn’t applied to all lenders. The amendment adds that if such a lender won a lawsuit challenging such a fee the, political subdivision that enacted the fee would be forced to pay the lender’s legal expenses. The amendment would allow those lenders to charge “contractual fees” and “a convenience fee or surcharge” for debit and credit card transactions.

This amendment could allow payday institutions in Liberty and, if the new local rules pass, in Springfield to sue the cities because of the imposed annual fee. The amendment quickly passed and was added to the bill that now heads to Governor Mike Parson, who is a Baptist, to either sign or veto.

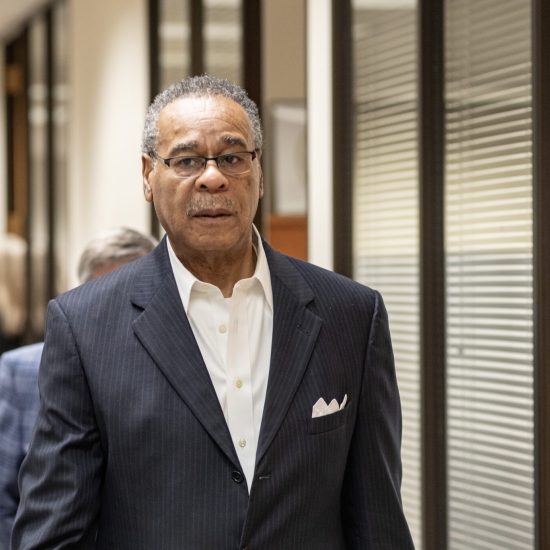

Harold Phillips speaks at the Heartland Advocacy in Action Conference co-sponsored by Word&Way on Feb. 8. He explained how the predatory lending regulations were enacted in Liberty. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Harold Phillips, a Baptist minister who serves on the Liberty City Council, criticized Trent’s amendment as “sneaky” and “blatant political greed” that “ignores local communities.” Phillips added in his comments to Word&Way that Trent “should be ashamed of himself.”

“Liberty voters spoke resoundingly at the ballot box last year that we want to protect our citizens in their times of need with adequate information before they might seek a predatory loan,” Phillips said about the measure that passed with 82% of the vote in November. “Liberty voters of goodwill, Liberty voters who value an economically vibrant community, and Liberty voters who value each other worked hard and addressed a need in our community.”

Bob Perry, a retired Baptist minister in Springfield who works with the University Hope Payday Rescue program at University Heights Baptist Church, also criticized the move.

“I am appalled that our legislature would use the occasion of the pandemic to sneak through legislation that clearly goes against the will of the majority of Missourians,” Perry told Word&Way. “Most Missourians want a reasonable cap on predatory lending, but the legislature refuses to enact such laws or regulations. Now it appears that they will try to thwart the will of the majority by limiting what local jurisdictions can do to regulate the payday and short-term installment industry.”

Bob Perry speaks at the Heartland Advocacy in Action Conference co-sponsored by Word&Way on Feb. 8. He explained how the University Hope Payday Rescue program works. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

“Sneaking provisions into a bill without proper hearings or opportunity for study seems very unethical,” Perry added. “I would hope the Governor would take a careful look at such catch-all bills and refuse to sign when they contain inappropriate add-ons.”

When questioned about the amendment, Trent told Word&Way he didn’t think it would protect payday lending institutions, insisting it instead would prevent “some kind of punitive fee or licensing” on the traditional installment lenders.

However, multiple attorneys who study payday lending regulations told Word&Way that while a payday loan wouldn’t normally count as a “traditional installment loan,” many payday lending institutions also have a traditional installment loan license. Rather than being two separate businesses, the multiple licenses could allow such a lender to claim the fee imposed because of their payday loans is disallowed by Trent’s measure since they are also a traditional installment loan lender.

One such lender already sued the city of Liberty, claiming they shouldn’t be regulated because they also provide traditional loans. With Trent’s measure mandating the court fees being paid if cities lose such a suit, advocates fear some officials might not risk fighting a lawsuit.

When told of the Liberty suit, Trent still said his bill wouldn’t empower institutions that offer payday loans.

“I think those things are partitioned,” he said.

Phillips, Perry, numerous other advocates, and some state legislators see it otherwise. Among those criticizing Trent’s amendment for its impact on payday regulations are the Northland Justice Coalition that spearheaded the Liberty effort, Faith Voices of Southwest Missouri that pushed the Springfield measure, and House Minority Leader Crystal Quade (a Democrat in Springfield).

Trent also told Word&Way he found it “kind of baffling” that opposition suddenly grew to his amendment since he had previously filed the language as a bill that hadn’t sparked controversy.

However, that bill, House Bill 2730, hadn’t yet even received a committee assignment, a status that would signal the bill has little chance of advancing. And if it had been assigned to a committee, it would’ve required a public hearing before any votes — which would’ve provided an opportunity for lawmakers to ask questions about the impact of the bill and for advocates and others to speak about the bill before any voting.

On the federal level, efforts also exist to protect predatory lending. A bipartisan group of two dozens U.S. lawmakers urged the Treasury Department and the Small Businesses Administration to allow payday lenders to qualify for the Paycheck Protection Program created to provide relief during the economic turmoil caused by coronavirus. The spokesperson for the group is Rep. Blaine Luetkemeyer, a Republican from Missouri. Advocates for ending predatory lending have instead urged various restrictions on such institutions to prevent them from profiting on the economic downturn.