Jake Hills, Unsplash

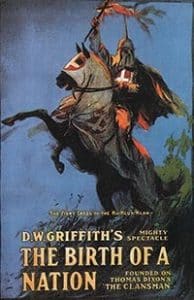

From The Birth of a Nation, the 1915 silent movie some historians blame for a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, to Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman more than 100 years later, movies have reflected and shaped Americans’ attitudes toward race, said Baylor University professor and popular culture observer Greg Garrett.

Movies tend to prompt conversations, and Garrett, professor of English at Baylor, wrote A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation to stimulate dialogue — in churches and elsewhere — about the lenses through which Americans view race.

In fact, conversations about race and movies with diverse audiences — including the Long, Long Way Film Festival at the Washington National Cathedral — helped give Garrett a perspective he would not have known “as a middle-aged and middle-class white man,” he said.

In fact, conversations about race and movies with diverse audiences — including the Long, Long Way Film Festival at the Washington National Cathedral — helped give Garrett a perspective he would not have known “as a middle-aged and middle-class white man,” he said.

‘Be seen, known and accepted’

Garrett particularly credited the insights he gained from Kelly Brown Douglas, an African-American priest who is canon theologian at the cathedral and inaugural dean of the Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary.

During a screening of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner at the Washington National Cathedral, Douglas explained why her first viewing of the movie as an 11-year-old meant so much for her. She recognized the movie was intended primarily for a white audience, and the story of the interracial couple was powerful but not of primary importance to her.

For Douglas, the key was seeing Sidney Poitier’s dignified portrayal of a proud black man, in contrast to the stereotypes she has seen in other popular entertainment.

“We all want to be seen, known and accepted,” Garrett said.

Garrett noted President Lyndon Johnson screened Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner at his ranch — the Texas White House — five decades after President Woodrow Wilson screened D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation at the White House.

Garrett traces changing attitudes and slow progress

In A Long, Long Way, Garrett traces the changes in Hollywood’s attitudes toward race, particularly focusing on African Americans.

“Similar stories could be told about anybody outside the white, male mainstream,” he said, adding he chose to concentrate on African Americans for personal reasons.

Greg Garrett

Growing up in the Deep South, Garrett said he long had been concerned about issues of race. But he became indebted to the black church tradition when one congregation welcomed him at a time when he spiritually was wandering.

“I was rescued by a historically African American church in East Austin,” he said.

Garrett said he rediscovered his Christian faith thanks to the hospitality and welcome he received “worshipping with people who didn’t look like me.”

He begins his book by carefully examining The Birth of a Nation, the groundbreaking 1915 movie that many cultural observers call the most influential motion picture in history. Its portrayal of the Reconstruction era reinforced and shaped attitudes about white supremacy and black inferiority for generations—particularly the way it presented black males as subhuman predators and a threat to pure white women, he noted.

It contributed to public attitudes that produced a spike in racially motivated lynching across the South, including the killing of Jesse Washington—a 17-year-old African American in Waco who was accused of raping and murdering a white woman, Garrett said.

Some historians link the 1915 silent movie “The Birth of a Nation” to a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

“There’s always a tension when it comes to whether movies reflect or shape opinions, but they certainly have a contributing effect, whether reinforcing attitudes or changing attitudes,” he said.

Garrett traces the evolution of Hollywood’s treatment of African Americans — from white actors in blackface portraying them as subhuman beasts, to caricatured stereotypes, to supporting roles that subtly began to acknowledge their humanity, to starring roles in movies still produced by and for whites, to movies that finally allow African Americans to tell their own stories, even if they often fail to be honored by the motion picture establishment.

‘Want to be an agent of reconciliation’

In each chapter, he offers theological and ethical reflections, drawing from Scripture and the writing of theologians past and present. He encourages white audiences, in particular, to ask how people outside the majority are depicted in movies and whether those depictions allow viewers to see the image of God in them.

Garrett has written four novels and multiple books on varied aspects of popular culture — music, television and comic books — but he considers A Long, Long Way his most important work.

“I hope readers will use the book as a way of launching the kind of conversations that films seem to make possible,” he said.

He recalled hearing Catherine Meeks, director of the Absalom Jones Episcopal Center for Racial Healing, speak at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City, challenging her audience to respond to the question Jesus asked the paralyzed man at the pool of Bethesda: “Do you want to be healed?”

“I hope people will read the book and respond to it the same way I responded to Catherine Meeks: ‘Yes, I want to be healed. I want to be an agent of reconciliation,’” Garrett said.

This article originally appeared at the Baptist Standard and is used by permission.