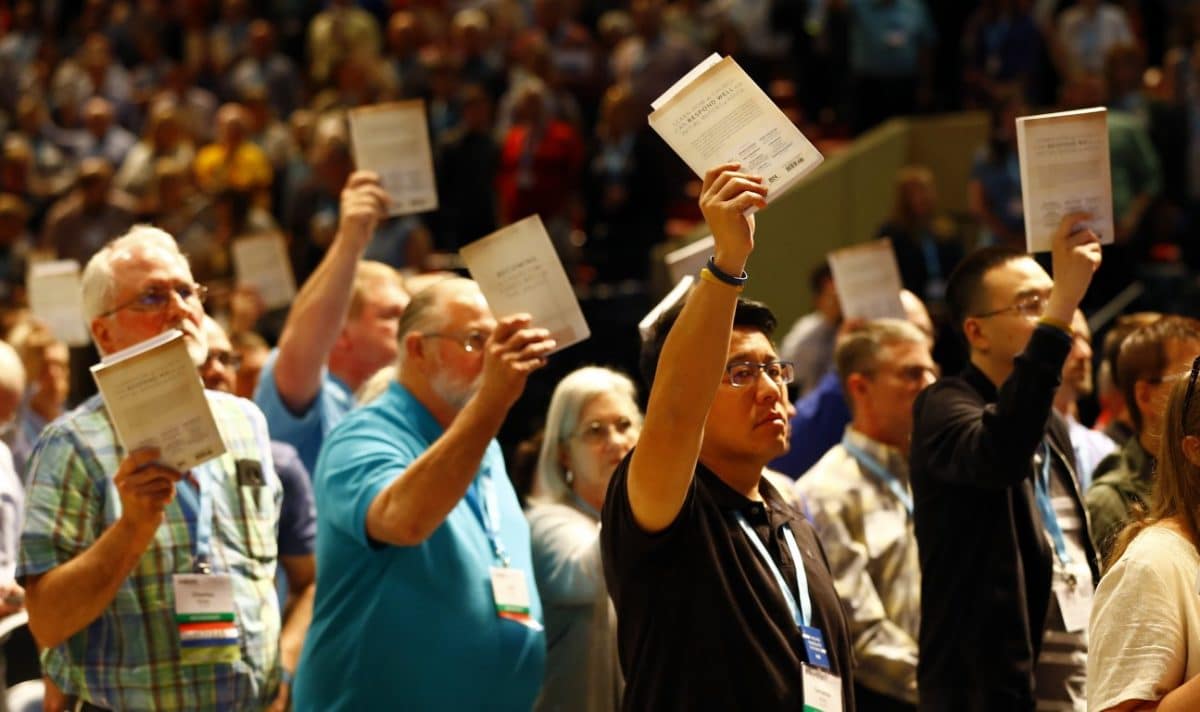

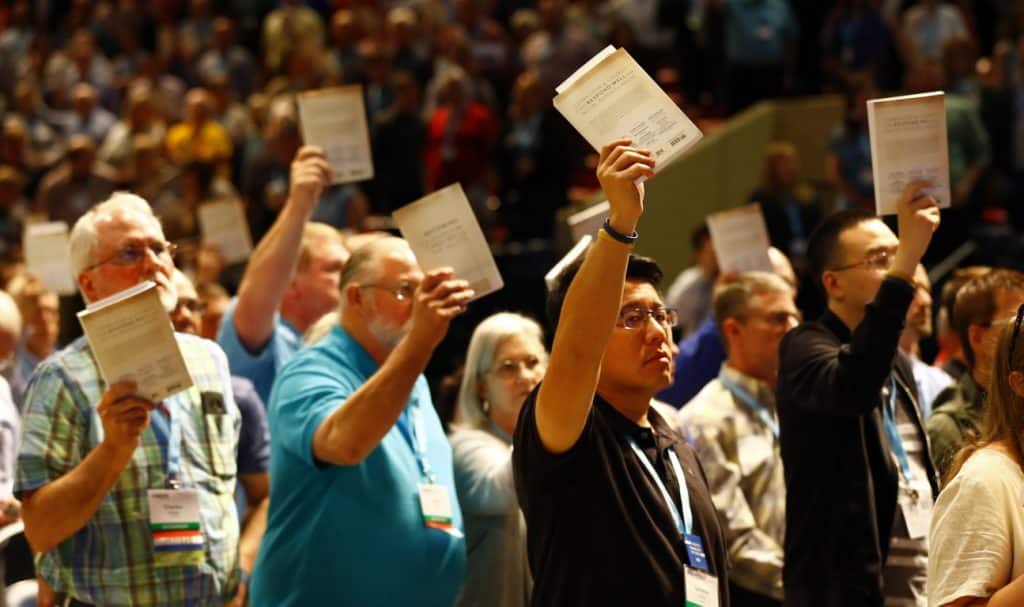

Messengers hold up SBC abuse handbooks while taking a challenge to stop sexual abuse during the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention at the Birmingham-Jefferson Convention Complex, June 12, 2019, in Birmingham, Alabama. RNS photo by Butch Dill

(RNS) — The Southern Baptist Convention will not hold its annual meeting as it regularly does each June. But issues its members have long grappled with — including race and the roles of women — continue to be points of controversy in the nation’s largest Protestant denomination.

In December, Founders Ministries, a neo-Calvinist evangelical group made up primarily of Southern Baptists, premiered a documentary called “By What Standard?: God’s Word, God’s Rule.”

The film includes selective footage of discussions around last year’s meeting about whether women should preach, juxtaposed with Founders Ministries head Tom Ascol speaking of motherhood as “the highest calling.” Much of the almost two-hour film that has had some 60,000 views online chronicles the passage of resolutions at the 2019 meeting, from one on “the evil of sexual abuse” to another on “critical race theory and intersectionality.”

Two months after the film’s release, the Conservative Baptist Network was founded, calling itself an alternative for dissatisfied Southern Baptists who might otherwise leave the denomination or stay and remain silent.

“A significant number of Southern Baptists are concerned about the apparent emphasis on social justice, Critical Race Theory, Intersectionality, and the redefining of biblical gender roles,” the network declared in its first news release.

The new network was launched at a time when the SBC continues to face decline. The SBC peaked in 2003 with 16,315,050 members. New statistical data released Thursday (June 4) shows 14,525,579 members in 2019, a decline of nearly 1.8 million members in 16 years. Membership is at its lowest level since 1985.

Some of the recent debate in the denomination has focused on the role of women in the church, including whether or not women can preach in Sunday morning worship services.

Much of the debate has focused on how the denomination speaks about race.

Before the recent events triggered by the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis under the knee of a police officer, Southern Baptists had been debating the meaning of critical race theory in particular.

Ascol said his primary regret about the cancellation of this year’s meeting — which had been scheduled for June 9-10 in Orlando, Florida, but was scrapped because of the coronavirus pandemic — is that he can’t walk to a microphone on the convention floor and ask for a reconsideration of what has come to be known as “Resolution 9.”

Tom Ascol of Founders Ministries. Video screenshot

The resolution, passed at the SBC’s annual meeting in 2019, states that “critical race theory and intersectionality should only be employed as analytical tools subordinate to Scripture — not as transcendent ideological frameworks.” It also notes that “while we denounce the misuse of critical race theory and intersectionality, we do not deny that ethnic, gender, and cultural distinctions exist and are a gift from God.”

Still, the resolution remains controversial.

“The Southern Baptist Convention needs to go on record saying that we rescind that resolution because we are opposed to racism and, because we are opposed to identity politics, we need to rescind Resolution 9,” Ascol said. “And I was looking forward to that opportunity.”

According to Southern Baptist polity, each meeting’s resolutions represent the thinking of the messengers, or delegates, attending that particular gathering. A new resolution could be adopted. But historically, old ones aren’t removed.

“That resolution that was passed will always be in the record books,” said Jon Wilke, media relations director for the SBC Executive Committee.

Glenn Bracey, an assistant professor in Villanova University’s Department of Sociology and Criminology, said critical race theory centers on a critique of conversations about race.

It calls for a focus on structural racism in institutions and “white collective activities around maintaining domination.” He said intersectionality focuses on ways social structures or laws leave some people without protection or subject to additional exploitation because their identities, such as being both black and female, intersect.

Pastor Stephen Feinstein, the California pastor and U.S. Army Reserve chaplain who originally proposed the contested resolution, said he hopes it “could be used to hold accountable anyone who actually does push CRT in SBC institutions.”

Feinstein said he believes critical race theory is “a true threat to biblical Christianity.” He said reactions to his original version and the final adopted one have fascinated him.

“Those who hoped to use my original proposal as proof that the SBC has been taken over by Marxists quickly turned against me as if I was a sell-out,” he said. “Yet, those who are committed to social justice (as defined by progressivism) also vilified me. Honesty makes enemies on both sides.”

Glenn Bracey. Photo by Kevin C. Brown

Bracey is an investigator with the Race, Religion, and Justice Project, which is studying Christianity and race in contemporary America.

The project’s researchers found in 2019 that 38% of white practicing Christians surveyed say the country “definitely” has a race problem, compared with 78% of black practicing Christians and 51% of the general population. Thirty-five percent of evangelicals — not broken down by race — gave the same response.

Bracey said the reaction to the resolution, including the stances of the two subgroups of Southern Baptists, reflects a white-male-dominated denomination with a “long and troubled” racial history, one that dates to a defense of slavery.

“It just speaks to the severe threat that people feel when the knowledge and perspective of women and people of color are treated as equal to the knowledge produced by white folks, white men in particular,” he said.

Bracey added that many who question critical race theory are not aware of its history. It is not only based on the work of law professors and students of the late 1970s and early 1980s but also scholars who draw on biblical language from the prophet Jeremiah and spiritual concepts such as respect for all people.

“What people don’t usually know is that it’s actually built largely by black Christians, frankly, using a lot of black Christian principles and references to Scripture,” he said. “There’s kind of a straw-man version of critical race theory that they’re arguing against that is totally divorced from the real critical race theory.”

Pastor Dwight McKissic, an African-American leader whose Texas church is affiliated with the SBC, said the latest disputes pale in comparison to the “worthwhile fight” about biblical inerrancy — the belief that the Bible is without error — that led to a so-called conservative resurgence in the denomination starting in the late 1970s.

The pushback over critical race theory and intersectionality — terms he said many are unfamiliar with or do not completely understand — is a different matter.

“It’s a smokescreen,” said McKissic, who worked to get Southern Baptists to accept a resolution condemning white supremacy in 2017 that was rejected and then adopted in the same meeting after a fierce backlash.

“It’s really white supremacy trying to control the narrative, that’s what it is.”

As the nation has faced recent protests from city to city about racial justice and police brutality, some Southern Baptists have spoken out about those issues.

“Southern Baptists must not only be known to stand for the sanctity of human life, but we must also be known to stand for the dignity of all human life regardless of the color of skin,” said Ronnie Floyd, president of the SBC’s Executive Committee as he opened an online prerecorded SBC Advance event on Tuesday. “We may say things through tweets or posts, but real change will only be seen through our conduct toward one another. And none of this will go away with violence, but only by developing relationships with each other, working together and resolving to press forward together in the spirit of Christ, who is the Prince of Peace.”

SBC President J.D. Greear offers a prayer to the church for healing from sexual abuse during the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention at the Birmingham-Jefferson Convention Complex, June 12, 2019, in Birmingham, Alabama. RNS photo by Butch Dill

Asked about the continuing differences among Southern Baptists on race and women’s roles, SBC President J.D. Greear said that he and the leaders of the denomination’s organizations, state conventions and local associations all affirm their statement of faith, the Baptist Faith and Message.

“This is something to celebrate and there is no drift away from that,” he said. “While the Bible teaches the complementary roles of men and women in creation, it also overturns any ideas of inequality of the sexes or male dominance.”

But, Greear said, if the convention had met in Orlando he would have made a change in a tradition that reflects the denomination’s racial history. Instead of using a gavel named for John A. Broadus, a slaveholder and a founding faculty member of the SBC’s flagship seminary, to open and close the gathering, Greear planned to use a different one, maybe even one named for a woman.

“I was planning on using the Judson gavel or the Annie Armstrong gavel this year in Orlando,” he said. “Adoniram Judson was a missionary that inspired me and I named my son after him. Annie Armstrong demonstrated the missionary spirit that I believe Southern Baptists should be about.”