On Monday (Oct. 12), trustees for Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, followed the request of SBTS President Al Mohler and voted against renaming buildings that honor the school’s enslaver founders. But while Mohler and SBTS insist names are important, they keep ignoring some names: those enslaved by the founders of the seminary.

Mohler insists the names of the founders stay on campus buildings because names matter. And he’s right. Who we honor — and who we don’t — says a lot about what values we cherish and who we want to be as a people.

Mohler also told the trustees they should leave the names of the enslaver founders because “we’re not going to erase our history in any respect or leave our history unaddressed.”

Norton Hall houses the president’s office at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

But names on a building aren’t how you teach history. Monuments, statues, and building names are about honor, not history. Removing a name from a building doesn’t remove that person from history, but removes an honor to them. That’s why the key person who has pushed for changing the names, Dwight McKissic, explained he wanted the honors removed from buildings but not the writings of the four men from the school’s library or classrooms.

And Mohler knows the names are about honor and not history because at the same meeting he led the trustees in vacating the Joseph Emerson Brown Chair of Christian theology (a position Mohler held as president) precisely because of Brown’s past support of slavery, the Confederacy, and convict leasing.

“We must ask whether any name is wrongly commemorated in our institutional life,” Mohler said to justify that decision. “We do not get to choose a history, but we do bear responsibility for who we commemorate and why.”

Mohler isn’t trying to erase the fact that Brown saved the seminary but instead just wanting to remove a commemoration of Brown. Erasing an honor does not erase history. But if Mohler is truly concerned about erasing history, he should turn his attention to those he and the school keep erasing.

Before the vote, Mohler gave the trustees an eight-page report urging them not to remove the names of the four enslaver founders. In the document, he uses the names of the four a total of 55 times. However, he doesn’t once write the names of the more than 50 people enslaved by those four men.

That’s what it means to erase history.

For years, SBTS whitewashed its slavery legacy. To the school’s credit, they issued a 71-page report in 2018 documenting the slavery and racism of its founders and other early leaders. That report documented that the four founders together enslaved more than 50 persons. This act of truth-telling remains important and deserves praise.

But the document lacked in a critical area. The report mostly leaves unstated the names of those enslaved by SBTS’s founders, even though it cites records that provide some names. A man enslaved by Manly is named in the report: Ben. But SBTS’s report spends several sentences talking about a couple enslaved by Boyce without naming them: George and Fanny. Other names might exist in the research consulted by SBTS, but those names didn’t make the report. While the four enslaver founders are named more than 380 times in the report, the 50-plus enslaved persons only get six named mentions of Ben on one page.

Unfortunately, most of the 50-plus names are likely lost to history like those of millions of other Black men, women, and children held in bondage in this nation. Too often their names are forgotten, their graves unmarked or overgrown, and their lives ignored. But their lives matter.

Mohler doesn’t seem to understand this.

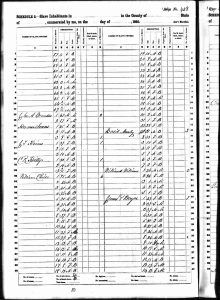

“As stewards of a Christian institution committed to the church of Jesus Christ, we also bear a stewardship of the dead,” he told the trustees. “Names of founders are on our buildings. Names of slaves are on the census documents.”

1860 census document counting (but not naming) those enslaved by Southern Baptist Theological Seminary founders.

But the names of the enslaved aren’t included on the census documents for SBTS’s four enslaver founders. Just how many people, listed by sex and age. Who needs to list names for “property” when all that matters is how much you have and how productive they might be for you?

That’s precisely why saying the names of the enslaved can serve as a powerful rebuke to the system of White Supremacy that birthed SBTS. Saying the names of the enslaved testifies to their God-given human dignity. Saying their names signals we won’t join their enslavers in attempting to erase their lives from history.

Mohler acknowledged to SBTS’s trustees that they need to do more “to be more faithful in telling our story, and the story of our founders with accuracy and biblical wholeness.” He called the 2018 report “a starting point,” adding that “telling the story with faithfulness is an ongoing project and commitment.” And he’s right. That work should continue with a focus on the enslaved.

So, here are five concrete steps Mohler and SBTS can take:

1. Document what can be learned about those enslaved by SBTS’s founders. Return to the archives and produce a supplemental report detailing as much as we know about the people enslaved by SBTS’s founders. The 2018 reported focused on SBTS’s leaders. This new report should focus on the enslaved. Can more names be discovered? Can small tidbits about their lives be learned? Can additional information about their purchase and treatment be uncovered? This is difficult work since we’ve tried to erase their history for so long, but SBTS should go the extra mile.

2. Say their names during key SBTS events. Mohler should honor those enslaved by SBTS’s founders by naming them during public events on campus. Say their names during Heritage Week activities. Say their names in the chapel named for an enslaver. Say their names during the ceremony when new faculty add their names to the confessional document written by an enslaver. Each class of students should know these names.

3. Name spaces on campus after those enslaved by SBTS’s founders. Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina — where SBTS was founded before moving to Louisville — previously conducted a similar study about its ties to slavery. Afterward, the school announced it would name a prominent space on campus the Abraham Sims Plaza in honor of a man enslaved by the school’s founder. SBTS should likewise name prominent places on campus after the enslaved persons like Ben, Fanny, and George. Any discovered portraits of such enslaved persons should also be added to a prominent place on campus, like the portrait of a woman enslaved by an SBTS founder that’s printed in SBTS’s 2018 report.

4. Create a campus memorial to those enslaved by SBTS’s founders. Many, if not most, of the names of the enslaved likely won’t be discovered by research. But all of those individuals should be remembered. Other schools are doing this. The University of Virginia recently finished such a memorial on its campus. And the College of William & Mary recently unveiled the design for its own such memorial. SBTS should likewise construct a memorial on a prominent campus location, perhaps right there in the shadow of the names of the enslavers. McKissic shared on his blog Tuesday (Oct 13) a letter he wrote last week to Mohler specifically urging such a memorial: “If the unnamed slaves are given a significant memorial, tribute prominently displayed on campus, it would go a long way toward reckoning and righting the wrong (the moral wrong) of the founders’ names being prominently displayed.”

5. Pay biblical reparations. On Monday, SBTS trustees voted to create a scholarship fund for Black SBTS students. That’s good. But it’s not enough. When Zacchaeus repented, he didn’t create a scholarship fund he controlled that ultimately benefitted himself. No, he gave his stolen wealth away fourfold. If SBTS manages to trace the lineage of those its founders enslaved, they could pay reparations to the descendants like Georgetown University is trying to do. And SBTS should pay reparations more broadly, such as to Simmons College of Kentucky, a Black Baptist school also in Louisville that was established by formerly enslaved persons.

Mohler and SBTS still have a chance to build upon their important 2018 report. It begins with a simple but holy act of saying names.

Ben, Fanny, George…