SALISBURY, North Carolina (RNS) — The Sunday morning service at Providence United Methodist Church last month began with a few praise songs, as usual, then an opening prayer. But before launching into his sermon, Aldana Allen offered a personal testimony.

“I want to begin by glorifying and thanking God once again for my life, my health and my strength,” Allen told his congregants, who listened to the sermon from their cars as part of the new coronavirus routine.

He then proceeded to relate a terrifying incident that happened to him the Sunday before.

On his way home from church, he stopped for gas. As he was driving away, he noticed he was being followed, Allen said. He took an alternate route just to make sure, but the person continued to follow him. As Allen finally pulled into his driveway in a suburb of Charlotte, so did his pursuer, who began revving his car, lunging forward and pulling back.

The standoff in the middle of Allen’s driveway continued for several minutes. Eventually, the pursuer drove off. It was an important reminder, he said, of humankind’s fallenness. He then delivered his sermon.

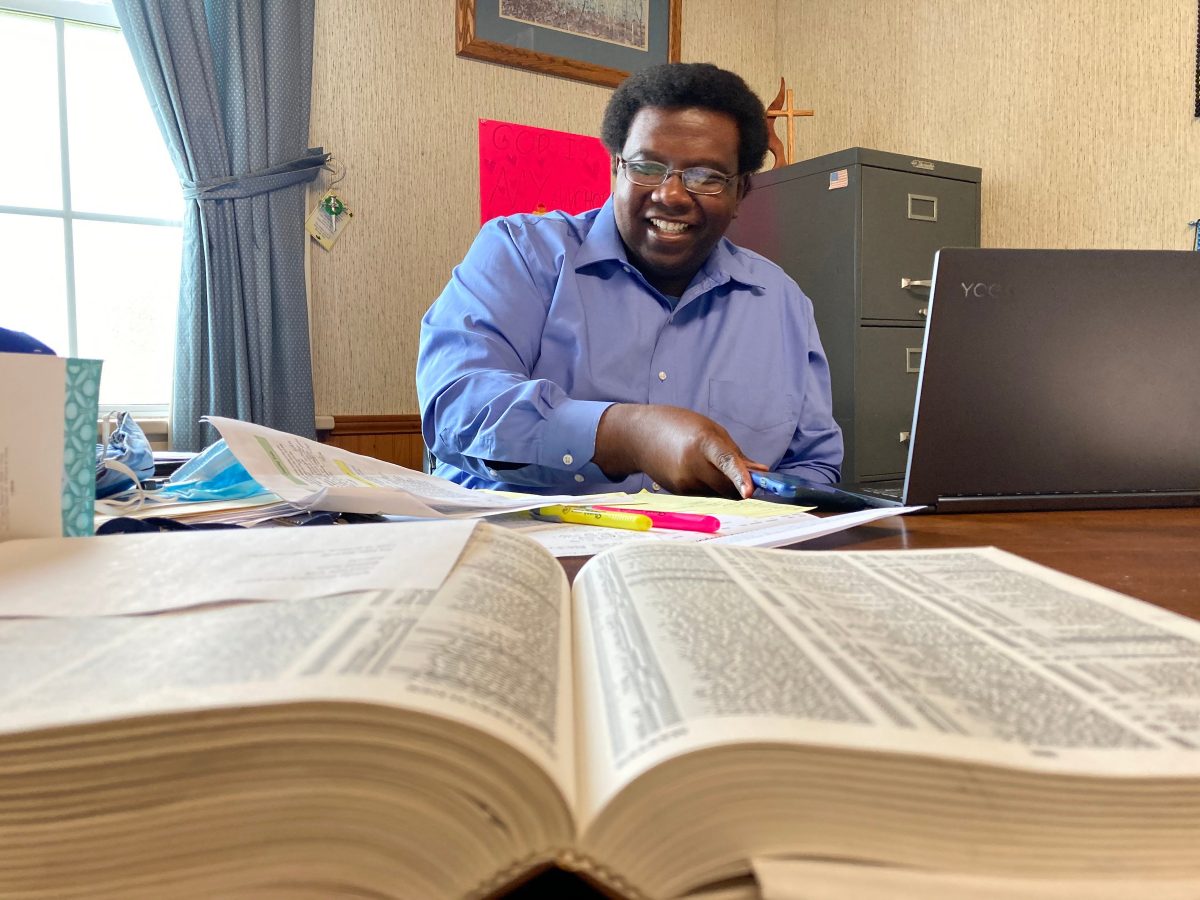

Aldana Allen works in his office at Providence United Methodist Church on Nov. 15, 2020, in Salisbury, North Carolina. (Yonat Shimron/Religion News Service)

Allen, who has led the small rural church for the past six years, is Black. His members are overwhelmingly White.

This North Carolina church about 40 miles southeast of Charlotte and several miles outside historic downtown Salisbury, is a microcosm of the old rural South. The country roads leading to the 182-year-old church are dotted with “Trump 2020” signs. Salisbury is the county seat of Rowan County, which voted for Trump over Biden by a 2-to-1 margin, 67% to 31%. The city is the birthplace of Bob Jones, the late Grand Dragon of the North Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Some homes here still fly the Confederate flag, and until this summer, a prominent bronze statue of an angel carrying a Confederate soldier stood on a pedestal right outside St. John’s Lutheran Church downtown.

Yet, at Providence United Methodist, race, one of the defining issues of 2020, is being negotiated in new ways. Allen, 48, doesn’t press the issue most Sundays. A Southerner, too, he walks a fine line — not wanting to alienate his congregants or risk a backlash. He did not tell his congregants that his pursuer that Sunday night was White (though he did tell the police who are investigating the incident). He did not point fingers. He did not issue a call to action.

But many congregants said they nonetheless understood.

“Hearing of his most recent experience tells us it’s still out there and it exists,” said the church’s youth leader, Marcie Petty, referring to racial intimidation. “It needs to stop.”

Allen is a Mississippi native who grew up in Tennessee, and has spent most of his career working in white churches. He has won the support of his congregants, in part by keeping the conversation comfortable and closely relating his experience to Christian themes. Along the way he has subtly raised his flocks’ awareness of how racism and racial discrimination continue to pose significant problems for African Americans.

Hesitant at First

The 300 or so congregants at Providence United Methodist did not choose Allen. Pastors in the United Methodist Church are appointed by bishops, normally for a year at a time.

In a commitment to create a multiracial church, United Methodist bishops have been assigning Black pastors to predominantly White congregations for about 50 years. In the Western North Carolina Conference, where Allen is based — covering Greensboro and areas west— there are 24 Black pastors among the conference’s 898 predominantly White churches.

“Our belief is that when people develop relationships, biases that are part of the racial context begin to diminish,” said Paul Leeland, bishop of the Western North Carolina Conference.

The conference has recently begun a larger conversation on how to be antiracist. For many churches, it’s a process. Most White churches are initially hesitant to accept a Black pastor, Leeland said. Providence, where Allen was first appointed in 2014, was no exception.

“There was apprehension when he was announced,” acknowledged Neal Hall, the church’s lay leader and a lifelong member. “It’s something we’ve never experienced.”

Hall, 59, said his own apprehension faded a few months after Allen’s arrival, when his daughter, who had been in declining health, died. Hall called Allen, who rushed to the hospital where Hall’s daughter Amber was ailing, and stayed with the family, comforting them, and reading Scripture passages into the early hours of the morning.

“He was my pastor in a time of need,” said Hall. “That bonds you.”

For Petty, Allen has been a “godly” role model — not only for the church youth but for her two boys, ages 14 and 21. Her eldest, John, had drifted away from the church under the church’s previous pastor. Allen visited her home and spoke to John about recommitting to Jesus and returning to church, which he did. She has been so impressed with Allen she has invited friends, curious about her Black pastor, to hear him preach.

“He brings people to see both sides and to know that there are changes in the world, and we need to be a part of those changes,” Petty said.

Allen, who graduated from the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta, said he was shaped by the Black liberation theology of James Cone, who saw justice for the poor and the outcast as the very heart of the Christian Gospel. Married to a Presbyterian minister, Allen said he believes providing genuine care to his congregants will reduce racial prejudice and bias.

In a paper for his doctoral program at Hood Theological Seminary, a historically Black school located in Salisbury, Allen recently wrote, “The more I can express our existential commonalities, and emphasize that God is the solution to the human predicament, the more the artificial barriers will fall.”

Stifling Healthy Conversation

Being a Black pastor in a predominantly White church in the age of Trump has been a challenge nonetheless. The president has defended White nationalists, criticized the Black Lives Matter movement, and generally exacerbated America’s racial divide.

The death of George Floyd, the Black Minneapolis man killed in police custody, and the subsequent protests that broke out across the nation, moved Allen to once again take a more direct approach.

Ten days after Floyd’s death, Allen used his Sunday sermon to expound on the New Testament story of the Good Samaritan and to recount a story from his youth. At a Fourth of July fireworks display in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, a white man drove by in a truck, flicked a beer bottle cap against his Allen’s head and then spat on him.

“That is the ugliest experience of racism I have experienced in my life, but it’s not the only one,” he told his congregants. “I share that story because of all the things that are going on in the news. I want you to know it’s real.”

He then went on to say that Americans and Christians in particular need to raise their awareness and show more empathy.

Yes, “All Lives Matter,” he said, but added: “We’re asking you to have empathy for this particular subset of all lives. All lives matter may be theologically correct, but what you are actually doing is stifling healthy conversation.”

Several members said they were moved.

“I will tell you personally I thought everything was taken care of after Obama was president,” said David Shields, a church member. “I thought we were in a post-racial society. Aldana drove home the point that there was a lot of work to be done.”

Not all Providence members appreciated the sermon. A handful felt that church was a place of refuge. They didn’t want to be thrust right back into the storm.

A six-week Bible study about race and reconciliation that Allen started soon afterward was poorly attended. Allen said he wasn’t sure if people didn’t want to engage the subject or were staying away from church because of pandemic fears.

“I hate it for him that the race thing came up, and you hear people saying that they’re tired of hearing about it,” said Pam Ervin, a member who chairs the church’s mission projects. “It’s sad that we couldn’t have these conversations.”

Allen, however, hasn’t given up. Before COVID-19, the church had sermon swaps and common meals with a predominantly Black church down the road, and he wants that relationship to continue. So far, church members say they’ve been able to see each other as people first, not Republicans and Democrats, but Allen is thinking of starting a Bible class on the nation’s political divides and how people might come together — perhaps around the time of President-elect Biden’s inauguration, he said.

Church members aren’t sure they can find unity on both sides of the political divide, but on racial issues they said their consciences have been pricked.

“I don’t think that Pastor Allen being here is accidental,” said Hall, the church lay leader. “It’s God loosening us up. Pastor Allen was something we needed, and God delivered because he knew these times were coming. He’s showing part of what that different way looks like.”