(RNS) — Jennie has tried to keep it together, she really has.

Her job demands nothing less. As a hospital chaplain for a Catholic health association in the Midwest, she has spent the past year shouldering the weighty burden of working with COVID-19 patients amid a ruthless pandemic that has taken the lives of more than 300,000 Americans. Sometimes she gets to work with patients on the road to recovery, but with infection rates skyrocketing nationwide, she has too often found herself sitting next to a hospital bed — her face obscured by an inhuman visage of mask and face shield — softly singing the hymn “It Is Well With My Soul” as a dying patient rattles out a final breath.

Over and over, she then turned to family members briefly granted access to their loved one, their newly tear-stained faces also hidden behind layers of fabric and plastic. And over and over, she has found the strength to help them mourn — pushing aside the knowledge that she can never know for certain whether they, too, are infected.

She says mustering this strength, at least in public, has been part of how she “survived” this difficult year. But when she sat down next to a hospital doctor to be vaccinated on Dec. 21, becoming one of the first faith leaders in the world to do so, she couldn’t stop the tears.

“I told the doctor: ‘I’m a little bit weepy today because, like … I don’t know how to explain it,’” said Jennie, who asked Religion News Service to withhold her last name so she could speak freely about her experience. “She looked at me and was like, ‘I was the same way. Out of all this darkness, hope is on the horizon.’”

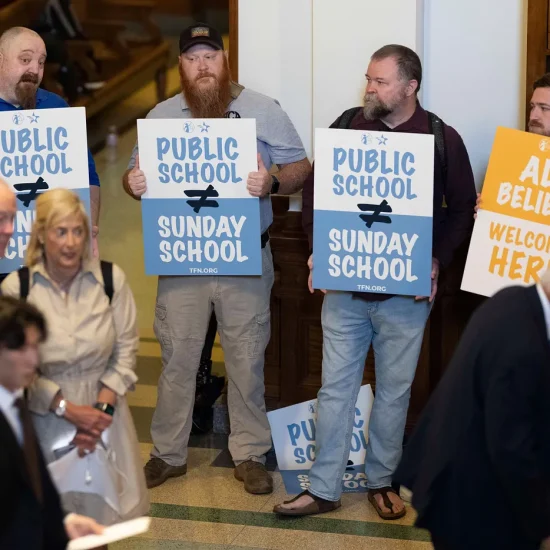

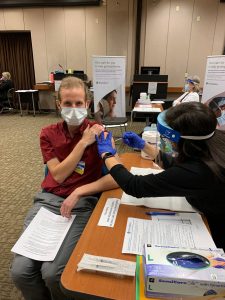

Daniel Russell, left, receives a COVID-19 vaccine in the Los Angeles area. (Religion News Service)

Variations of this complicated feeling — a mixture of hope, euphoria, and lingering despair — were reported to RNS by a number of hospital chaplains who were vaccinated in recent days. Even while they rolled up their sleeves to join other frontline workers as some of the first to be gifted with human-made immunity to the novel coronavirus, many reflected on the work that led them to the historic moment — jobs that are sometimes harrowing, sometimes beautiful, and always deeply felt.

Some chaplains who spoke to RNS expressed surprise that they were included in the first round of vaccinations.

“Chaplains have a really valuable role on the care team, but it’s not all the time we are told, ‘You’re just as important,’” Jennie said.

But even as protocols and systems vary depending on the hospital or the state, the exposure many chaplains have to COVID-19 is very real. Daniel Russell, a Fuller Seminary graduate who works as a hospital and hospice chaplain in the Los Angeles area, regularly visits COVID units. Before each session, he stops at the black tape that marks the entrance to the COVID hallway to don gloves, a gown and a “PAPR” — a futuristic white helmet that encases his entire face.

Then he enters a patient’s room, taps on a phone or iPad, and holds it aloft so family members can see their loved one via video chat. Sometimes, if the patient is not intubated, they talk. Sometimes they pray together. Sometimes the families burst into songs, or even hymns.

“It’s so clear, every time, that their loved one is so loved,” he said. “As a chaplain, it’s OK to tear up. But the amount of crying I’ve done this year … it’s hard.”

All chaplains who spoke to RNS reported a notable change in the tenor of their conversations with others this year. Andy Karlson, a Unitarian Universalist chaplain for St. Mary’s hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, observed patients are open to longer conversations because “there’s just a loneliness.” Anxiety is paramount, as are profound questions about why a greater power would allow them or their loved one to suffer.

And even when they don’t hear such questions from patients, they hear them from medical personnel.

“We do as much staff support as we do patient support,” Karlson said, noting that while all such conversations are part of his job as a chaplain, they also put him at risk of exposure.

Indeed, COVID-19 has not spared faith leaders who serve the sick. In April, a chaplain at NYU Langone Health, Rabbi Mordecai Katz, reportedly succumbed to the disease.

And then there’s the emotional and spiritual toll. Russell, who is pursuing ordination with the Free Methodist Church, said he recently began lighting candles as part of his Advent practice when he returns home at night. As the death toll mounts, he has taken to thinking of each patient who died that day as he sets each wick alight. He intends to continue the practice after Advent, but acknowledged it can be overwhelming.

“This is really the first time I’ve processed all of this,” Russell said.

Chaplain Kevin Deegan prays for COVID-19 patient Pedro Basulto while on a video call with the patient’s daughter, Grace, at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in the Mission Hills section of Los Angeles on Nov. 19, 2020. (Jae C. Hong/Associated Press)

These and other experiences created the backdrop for hospital chaplains across the country as they received emails this month informing them they were in line to receive the vaccine. Again, systems vary: Some chaplains have already gotten the vaccine; others told RNS they expect to receive it sometime in the next month, and still others aren’t sure when they will get the shots.

But regardless of when they get the vaccine, many say their decision to do so will be driven in part by faith-fueled altruism. Hiram L. Brett, chaplain and coordinator of spiritual services at Connecticut Mental Health Center, recently told the Yale School of Medicine that his choice to get vaccinated was informed by his faith and his desire to quell vaccine hesitancy among religious groups — particularly his fellow African American Christians.

“I’m a preacher, so I have to say this: In this situation I would lean to faith as opposed to fear,” said Brett. “If you’re choosing to keep yourself exposed to the virus with the potentiality that you don’t know how it will affect you or your loved ones, are you letting fear drive you? I would opt toward faith and lean to the vaccine.”

Karlson said he talked with his family about getting the shot, and acknowledged it made him “a little afraid.” But he also felt driven to set a good example for his children — “I want them to see their dad doing his part,” he said.

And, like Brett, he felt compelled by his faith.

“I trust God will be with me,” he said. “I can lean into my faith for this.”

When he finally pulled up his shirt to receive the vaccine — a quick, almost painless prick just beneath a tattoo — he suddenly found himself engulfed by the enormity of it all.

“I was trying to play it cool, but I could feel the gravity, the weight of the pandemic,” he said. “We’re having a 9/11 of deaths every day. We’ve had to remap the structure of our whole society. We’re facing this exacerbated wealth gap — communities of color and people on the margins are being hit incredibly hard by this. Feeling that, as I was taking off my sweater and rolling up my sleeves … it was heavy, and hopeful.”

Jennie felt similarly. Although some have invoked faith as a reason to resist vaccines or mask-wearing during the pandemic, she saw the shot as an embodiment of Jesus Christ’s command to care for others.

“The golden rule is treating your neighbor as yourself,” she said. “I would hope my neighbor would care for my well-being enough to also get the vaccine, and to protect themselves and me and others they interact with. So why would I not do the same?”

As for Russell, the moment took on a liturgical significance. For him, the pandemic has been shrouded in shadows: He often works nights, shuffling around hospital hallways that could feel barren even before the pandemic. It has been grueling, difficult work, and he stressed it is far from over: Vaccine rollout will take many months, and patients will still need him after the pandemic, coronavirus or no.

Important things will continue to happen at night; the Christmas story, after all, occurred in darkness.

“We continue to show up for them,” he said. “We continue to grieve.”

But as the Pfizer vaccine entered his arm on Dec. 17 — just four days before the winter solstice — he recalled that even in a year plagued with sorrow, there have been moments of joy. At his hospital, staff have developed a ritual of sorts: Whenever a patient recovers and is released from the COVID unit, they play the song “Here Comes the Sun” by the Beatles.

Perhaps, he thought, morning has finally come.

“The days are going to begin to get longer again, and I felt such a sense of joy — like Christmas really was here,” he said. “It’s actually happening. The sun is coming.”