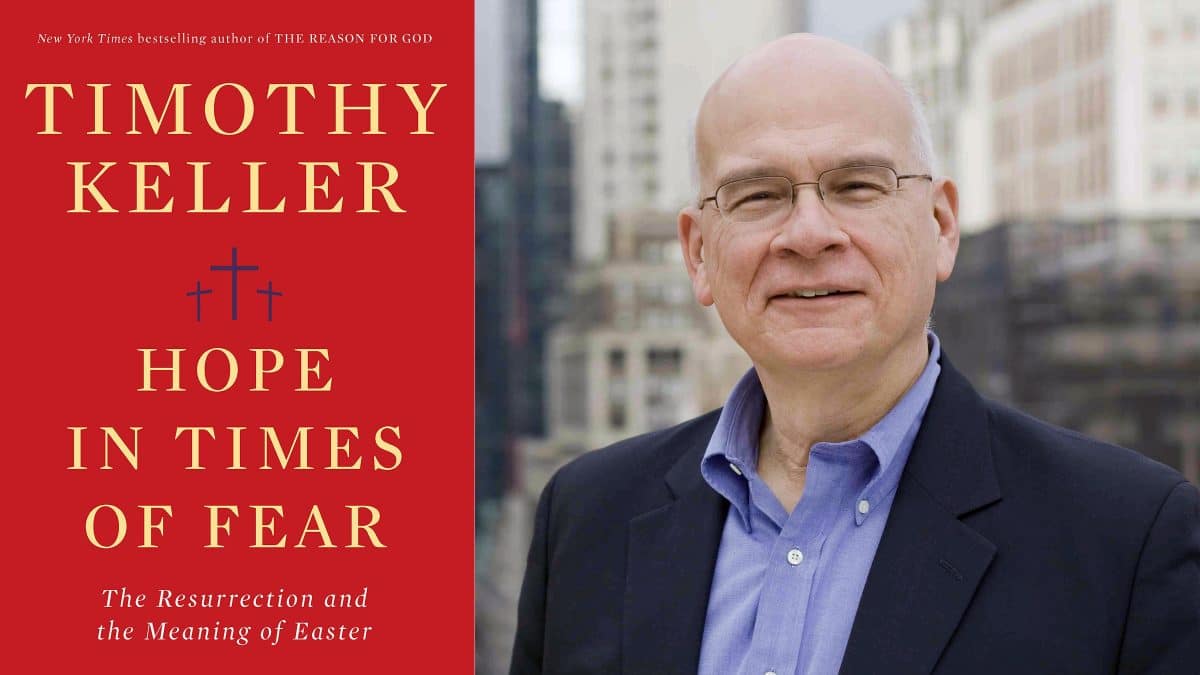

(RNS) — I was a seasoned flyer in December of 2016 when the plane carrying me to my interview with Pastor Tim Keller started its descent into New York, so my jitters weren’t due to landing at LaGuardia. I was a newbie journalist — feeling uncertain about my future and vulnerable about meeting the influential thought leader and church planter.

Keller was the pastor who had conquered Manhattan, starting one of the most popular evangelical churches (now five churches up and down the borough) in a city that prays even less than it sleeps.

To be honest I was so green I hadn’t even grasped what Keller meant to the Christian world until, a few weeks before, I mentioned it to a friend whom I was interviewing and he reeled off Tim’s resume: founder of Redeemer Presbyterian Church; chairman of City to City, which trains pastors all over the world; author of multiple New York Times bestselling books.

Tim’s list of accomplishments did not match what I found when I was ushered into his office that December afternoon. Tim’s office was small, quaint, more like an intern’s quarters. I tried not to knock into anything as the camera man set up his equipment.

“Hi, my name is Tim” is how our relationship began. In my earlier career, I had been around enough leaders who were very conscious of who they were. Not so with Tim. He is comfortable with who he is, but, more importantly, he wants to make sure that you’re comfortable, too.

Bespectacled and more professorial than pastoral at first glance, Keller, now 70, is nevertheless warm and transparent. Before I could ask my first question, I realized I wanted to be his friend, which is what we have been for the last four years.

As in any good friendship, our subsequent interviews — number four coming just March 5 by Zoom — have picked up where we left off at the end of the previous one. But I was nervous again.

Last May, Tim was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and though he appears to be doing well, I wondered whether we would be able to just talk as before. But with Tim, there never seems to be an agenda, which may explain why he succeeded in New York amid a sea of motives and agendas.

As we caught up with each other’s news and walked through current events, I teased him about a recent set of viral tweets in which he’d weighed in on race, justice, and the Southern Baptist Convention leaders’ rejection of critical race theory.

“You’re hot right now,” I joked.

“Almost everything is hot right now. It’s hard to not be ‘hot’ with where we’re at in our culture when it comes to race and justice issues,” he said.

But Keller, low-key as he is, makes his own heat. He is one of the few major evangelical leaders who has been up front in saying that as Christ followers we need to embrace a multiethnic world. He takes stands when it comes to biblical justice. Supporters and critics alike label his comments “controversial,” but Tim is doing what God called him to do, not what he thinks will sell books. I start to ask him where his authenticity comes from, but before I can, he’s asking what I’ve been up to.

Only when we bring up his new book for Easter, Hope in Times of Fear: The Resurrection and the Meaning of Easter, does it become apparent that he is thinking seriously about the last chapter in his life. During the writing process, Tim said, “the only way I could face the future is because I believed in the resurrection.”

Only when we bring up his new book for Easter, Hope in Times of Fear: The Resurrection and the Meaning of Easter, does it become apparent that he is thinking seriously about the last chapter in his life. During the writing process, Tim said, “the only way I could face the future is because I believed in the resurrection.”

And the book, which Tim says he studied the most carefully to write, explains just how that belief comes out of Scripture.

“I go line by line, explaining Scripture step by step,” Tim said. “I believe that if you’re going to write a book on the resurrection, you have to ask ‘did it happen?’”

It’s the hopeful theme of resurrection that gave Tim the strength to write it, most of which was written while he was undergoing treatment.

“I had plenty of time to write,” he said, “and even when I didn’t feel up to it during the chemotherapy, I would write.”

Despite the fact that he had only 25% of it written when he got his diagnosis, Hope in Times of Fear, a companion to a Christmas book he released in 2016, doesn’t focus on Tim’s journey with cancer.

“Except towards the end of the book,” Tim said. “I wanted the book to focus primarily on the resurrection and the hope that we have.”

If it’s not about his cancer, it’s about many topics we don’t immediately connect with the Easter story.

“Issues such as race relations, justice, and apologetics are evoked in the resurrection message,” Tim said.

“Christians believed that there was only one God and everyone should worship him regardless of their race, ethnicity, class, nationality, or vocation, or of any other status,” he writes. “The radical implication was that your faith in God was not merely independent of your ethnicity — it was more fundamental to who you were than your ethnicity.”

As a Black man who has ministered largely in white evangelical churches, I’ve always felt welcome to talk with Tim about race and not be chastised for it. Tim sympathized with the struggle that I and other African American Christians have faced. As extremism has taken hold in the culture, he said, “I’m understanding what it feels like a little, what you’ve had to deal with your entire life as a Black man living in this space.”

Tim said he understood that not only standing up for racial and social justice but finding a spiritual home where one feels free to express that can be difficult. “Most of us trying to do the right thing, we’re asking ourselves, ‘Where do I belong?’”

He is now thinking about his own place in the life he has left.

“When I was told that I had cancer,” Tim said, “I wrote down two words in my journal — ‘sanctification’ and ‘focus.’ I wanted to focus on what would be the best thing to do, and do that only and make a contribution to that.”

Being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer “has helped Kathy and I grow, and we wouldn’t want to go back to the way things were,” he said. “I believe that God put something in my life such as pancreatic cancer that has caused me to grow like I’ve wanted to. We’ve been happier and closer in this season.”

“I’ve already experienced death and the resurrection,” he said, “the death of dreams: I probably won’t see my grandchildren grow up, and I don’t want Kathy to outlive me.”

But when he goes, he feels his work is done. When it comes to assignments and projects, “there isn’t a single thing here that I will miss doing,” he said.

As we go to say goodbye, I feel sorrowful nonetheless, and seeing it, Tim, as only he can do, offers words of hope: “I believe the resurrection did happen, which is why everything is going to be okay.”

Maina Mwaura is a speaker and writer.