(RNS) — Last year on March 3, the Rev. Wolfgang Herz-Lane got a call at home from a member of his congregation.

“That guy they’re talking about in the news,” the congregant said, “that’s me.”

He was referring to news reports about the first North Carolinian to be diagnosed with COVID-19. That person, who declined to be identified, is a member of Herz-Lane’s church, Christ the King Lutheran in Cary, a town west of Raleigh, the capital.

Herz-Lane said the man recovered and is doing well. So is the church.

The congregation held its last indoor service a few days after that call. But it has not spent the past year standing still. The pandemic has transformed the 1,570-member church.

A few months into the pandemic, the congregation decided it would transition permanently to a “hybrid” model, conducting online worship that will continue even after in-person worship returns April 25 for 50 preregistered congregants. A few weeks ago, it welcomed its first nonresident member, a Maryland woman who does not expect to worship in person but was able to attend the required new-member class online.

There’s also a new prayer garden and a labyrinth walk — for those who live nearby but don’t want to risk an indoor service.

The coronavirus has “redefined for me what church is going to be like and what the definition of membership is,” said Herz-Lane.

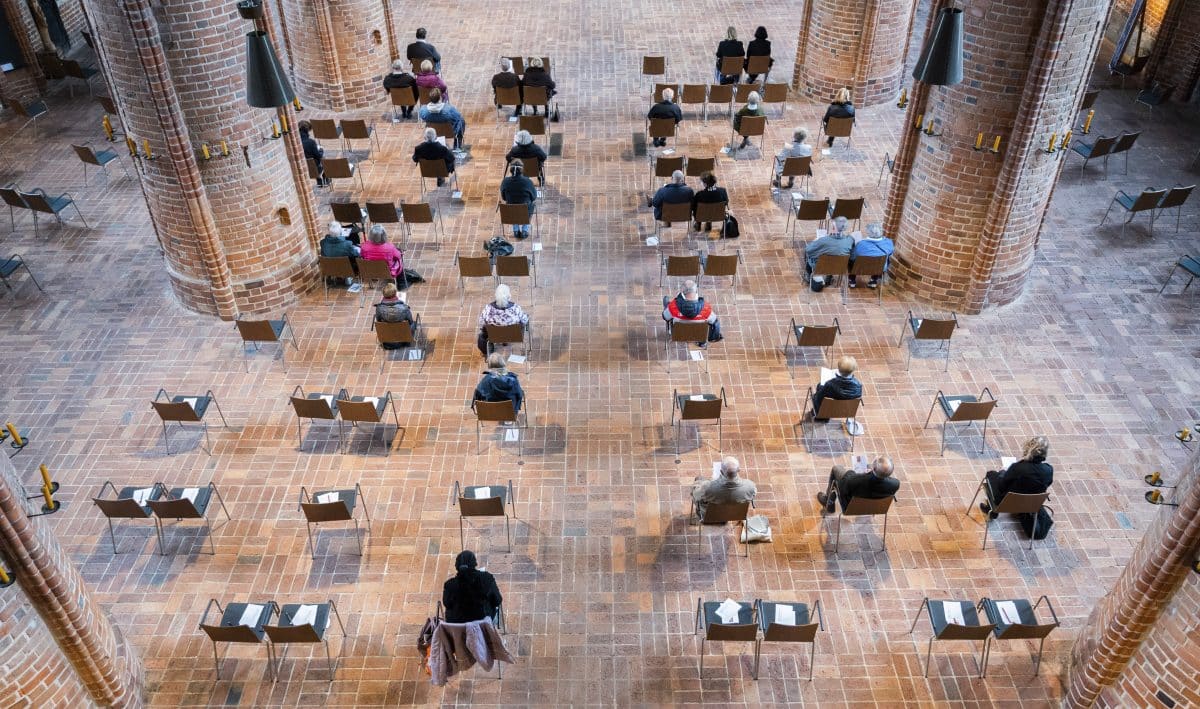

Worshipers celebrate a Good Friday service at the Marktkirche in Hanover, Germany, on April 2, 2021. (Julian Stratenschulte/dpa via AP)

Exactly how the COVID-19 pandemic has reconfigured American religion is not yet clear. A recent Gallup poll suggested the virus was at least partly responsible for pushing formal church membership past what some regard as an alarming tipping point: Fewer than half of American Christians, Gallup reported, now belong to a church.

But as U.S. Christians celebrate a second Easter under pandemic rules — their own or those imposed by government or denominational guidelines — churches are reckoning with new ways of volunteering, stewardship and, above all, worshipping. Many will be looking at Easter services this year and wondering if they are not glimpsing the future of the church.

“The truth is, those numbers have been declining for 50 years,” said Herz-Lane. “The pandemic accelerated trends that are already there.”

Some churches are not giving in to any new normal quite yet. The nearly 300-year-old Old South Union Church, a United Church of Christ outpost in Weymouth, Massachusetts, has gone back and forth over the past year, both meeting online and holding hybrid services, with a fraction of their 500 members in the pews, with most watching from home.

On Easter, however, Old South Union will go back to online only, ceding the sanctuary to a full-blown Easter service with traditional choirs, including a bell choir and brass ensemble.

“One of our deacons put it well,” said the Rev. Jennie Barrett Siegal, the senior pastor. “We wanted to have a service that felt like Easter, not just another service that happened to fall on Easter.”

Other congregations have no choice but to improvise their celebration. Before the pandemic, the Anthology Church, a Southern Baptist congregation in the Studio City neighborhood of Los Angeles, had been meeting in a local community center on Sundays. With the center still closed despite the gradual lifting of restrictions by the city, Anthology’s pastor, the Rev. D.J. Jenkins, began scouting for a church where his flock could hold an outdoor service.

All of the churches he called declined. Undaunted, he reached out to the rabbis at two synagogues that participate with Anthology in a local interfaith food pantry. This Sunday, Jenkins will lead an Easter service on the grounds of Temple Beth Hillel, a Reform congregation.

Though Easter normally draws about 200 worshippers, Sunday’s gathering will be limited to about 50, with masks and temperature checks required. The hymns will be played on a single guitar and a cajón, a box-shaped percussion instrument. As unfamiliar and modest as Easter will be, Jenkins will be grateful just to be together.

“It’s going to be, ‘Oh my gosh, we are all together and we are singing,’” he said. “It’s going to be therapeutic in that regard.”

Different doesn’t always mean diminished; the pandemic has pushed some churches to broaden their appeal. St. John’s Lutheran Church in Elkhorn, Wisconsin, part of Lutheran Congregations in Mission for Christ, has found glimmers of hope in the church’s annual Easter egg hunt. Normally an Easter-morning affair that brought out a few dozen families from the congregation to search for prize-filled plastic eggs, this year’s hunt has turned into a weeklong text message-based scavenger hunt that has pushed congregants out into the community and involved people who had never come to the church.

A banner outside St. John’s gives the first clue to the Easter Jam Family Egg Hunt, explained Stephen Quist, who co-leads the church’s children and family ministry with his wife, Cassie. By texting clues to a phone number on the banner, participants are led to a dozen or so locations around town and eventually back to church, where they get a prize pack full of Easter eggs and candy, as well as information about the church’s Easter Sunday services — online, outdoors and in the sanctuary.

St. John’s already was thinking of moving away from its traditional Easter egg hunt to try new things when COVID-19 hit last year, he said. Now it has found a new activity that involves the whole community.

“I would say that COVID has maybe expedited, forced our hand in the direction we’re probably headed anyway,” Quist said. “There is hope in all this, and the Lord has a plan for everything.”

So, it seems, do many ministers. If nothing else, the dislocations of COVID-19 have prompted creative liturgical and logistical solutions, from squirt-gun distribution of holy water to Lenten ashes imposed with cotton swabs onto hands stuck out of car windows. This Easter gives churches a chance to put on display all they’ve learned in the past 12 months and more.

At gospel singer Deitrick Haddon’s 5-year-old nondenominational Hill City Church in Los Angeles, the 300 weekly attendees haven’t met in person for a year. But its “Resurrection Sunday” outdoor service will be a model of socially distanced worship.

Haddon, who has a Pentecostal background, plans for his predominantly Black church to meet outdoors in the courtyard of a theater near Azusa Street, the site of an early 20th-century revival that was instrumental to the birth of Pentecostalism. The ushers have been renamed for the occasion.

“We call them our social distance warriors,” he said. “They’ll be there to help keep the distance and keep people in compliance with that.”

Along with “sanitation stations,” where people can use hand sanitizers or running water to clean their hands, “there will be posters and things to inform people how we’re operating at that event. We’re going to do the best we can to keep people informed and keep it a safe environment for worshippers.”

The LA congregation is taking additional steps to address COVID-19 that day. Working with Los Angeles County’s public health officials, it plans to offer 200 doses of the Moderna vaccine on a first-come, first-served basis for those in eligible groups.

At the Washington National Cathedral, the stage for national prayer services and four presidential funerals, Communion has not been offered for a year.

“We’ve been using a prayer for Spiritual Communion instead,” said Kevin Eckstrom, the cathedral’s chief communications officer. “The elements are consecrated each week as part of the Sunday Eucharist but are not consumed.”

But come Sunday afternoon, clergy will be positioned on both sides of the drive that snakes around the cathedral’s property to distribute Communion wafers.

“There’s a lot of pent-up desire for access to Communion, so we invited the Cathedral family to receive it on Easter Sunday,” he said. “Communion will be distributed by clergy, wearing masks and gloves, to people who drive up.”

The cathedral has invited members of its congregation and volunteers as well as the more than 6,000 people who regularly watch its Sunday services online.

Eventually, with enough vaccines and warm weather, scenes like this will become odd memories of a sad time. Americans of whatever faith will return to being, if not elbow to elbow, then comfortable sharing pews and prayer halls and will become accustomed again to sharing meals, coffee, and even hugs after services.

At St. Anthony Catholic Church, in the Southern Californian city of San Gabriel, the Rev. Austin Doran said his parish, made up of Spanish-speaking and working-class Latinos who were hit disproportionately hard by the pandemic, is not quite ready yet to hold indoor worship. A number of outdoor services will be held.

On Palm Sunday, Doran said he saw more older parishioners, who had been vaccinated, as well as more parents with their children attend outdoor worship. Doran figured that with more children back in school, parents feel more comfortable taking their kids out. But if there are signs of hopefulness, “there’s still a lot of sadness out there,” Doran said.

“I think there’s humility. We’ve realized, ‘hey we’re frail. We’re human,’” Doran said. “There’s a greater sense of solidarity.”

The pandemic, he said, has taught some painful lessons.

“People in the parish have shown they’re thinking not just about themselves, but about each other. Helping people with food, to pay their bills,” Doran said, “that’s all blossomed.”

But Doran is ready to move forward into whatever comes next. Thinking back to last year’s Holy Week, when the church’s services were being streamed from an empty parish, “it was absolutely creepy,” said the priest.

At least there’s a congregation now, Doran said.

“When you say a prayer, you get a response,” Doran said. “That’s a big difference.”