For many American Christians there is no conflict between God and country. Following Jesus and belonging to their nation go hand-in-hand. Indeed, the full expression of faith and citizenship requires combining both identities. To be a “good Christian” is to be a “good American” and vice versa.

Scholars of American religion describe this conflation of cultural identities as Christian Nationalism. Specifically focusing on a segment of conservative White believers who strongly embrace such ideas, these researchers warn such ideology (despite being unmoored from traditional Christian teaching) can be used to justify anti-democratic practices, such as restrictions on voting and political violence. The presence of Christian symbols at the Capitol insurrection on January 6th was an egregious example.

Indiana University’s Center for the Study of Religion & American Culture recently held an online mini-conference examining “White Christian Nationalism in the United States.” Two separate panels, one focused on academic scholarship and a second on public expression, sought to understand the historic roots, modes of operation, and contemporary impacts of this potent and problematic cultural identity.

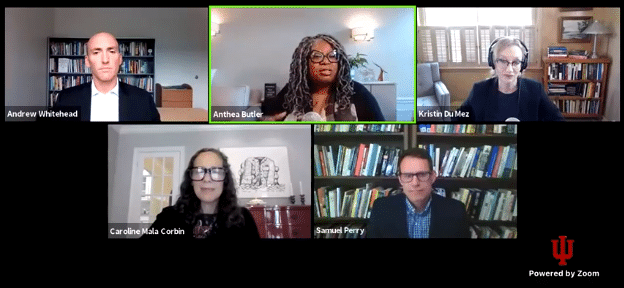

Screengrab of the first session of “White Christian Nationalism in the United States,” with (clockwise from top left) Andrew Whitehead, Anthea Butler, Kristin Kobes Du Mez, Samuel Perry, and Caroline Mala Corbin.

Seeking to make this terminology more concrete, Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a Calvin College historian and author of Jesus and John Wayne, defined the movement as animated by “the idea that America was founded as a Christian nation and must be defended as such.” She added, “It involves defending the privileged space of White Christianity within American society,” noting that “the adjective ‘White’ is important in all of this.”

Samuel Perry, a sociologist and co-author of Taking America Back for God, agreed that White Christian Nationalism was more than a belief system. In his words, it is “both a political theology that people hold at an individual level and a political strategy” that is designed to “bring about favored goals.”

The first set of conference panelists unanimously suggested that a sense of dislocation and illegitimate loss of status motivated such thinking and action. Caroline Mala Corbin of the University of Miami School of Law said that “[White Christian Nationalism] creates an ingroup of Christians and an outgroup of non-Christians.” This leads to defining true Americans according to their confession as Christian, implying that non-Christians are of a lower status.

“Roughly half of Americans are walking around this country thinking Christianity is a prerequisite to true belonging and true citizenship,” continued Corbin.

A sense of privilege and entitlement afforded to people on account of a racialized understanding of religion is the crux of what white Christian nationalism is about. As Perry noted, “All you have to think is that this language of Christianity and national identity favors people like me.”

When these assumptions are no longer operative, those enjoying their benefits grow angry. It morphs into what Du Mez described as a “militant defense of Christian America.”

Indeed, as the United State changes politically, demographically, and religiously, many conservative white evangelicals voice feelings of grievance and frustrations at displacement. This feeds into historical perceptions of alienation within those communities.

“There’s a narrative of evangelicals that they’ve always been persecuted,” remarked Anthea Butler, chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. “It really is the loss of privilege. The idea that I’m losing something that I won’t be able to get back to a group of people that don’t deserve it.”

Screengrab of the first session of “White Christian Nationalism in the United States,” with (clockwise from top left) Amanda Tyler, Jack Jenkins, Jemar Tisby, Angela Denker, and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove.

While the events of Jan. 6 remain unjustifiable, such animosity and ire among this group helps render them more understandable. Believing the fundamental principles of the nation are being lost, those affirming such principles go to extreme lengths in seeking to “defend” them.

The participants of this conference provided explanations of White Christian Nationalism’s complexity. Yet, the takeaway for followers of Jesus is simple to see. Once the phenomenon is understood, then its threat must be confronted and its dangerous, heretical ideas opposed.

As the Christian activist Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove succinctly put it, “I’m concerned about Christian Nationalism because I think it’s a threat to the soul.”