(RNS) — For many Americans, Pat Robertson, the Christian television pioneer and onetime presidential candidate, will always be remembered for his wacky pronouncements made at inflection points of American history.

“I don’t think I’d be waving those flags in God’s face if I were you,” he warned Orlando, Florida, city leaders in 1998 when they flew rainbow flags downtown in honor of Gay Days at Disney World. “This is not a message of hate — this is a message of redemption. But a condition like this will bring about the destruction of your nation. It’ll bring about terrorist bombs; it’ll bring earthquakes, tornadoes, and possibly a meteor.”

After the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the twin towers, Robertson said he agreed with Jerry Falwell, his guest on his signature talkshow, The 700 Club, that responsibility for the attacks on the United States fell to pagans, abortionists, feminists, gays, and lesbians.

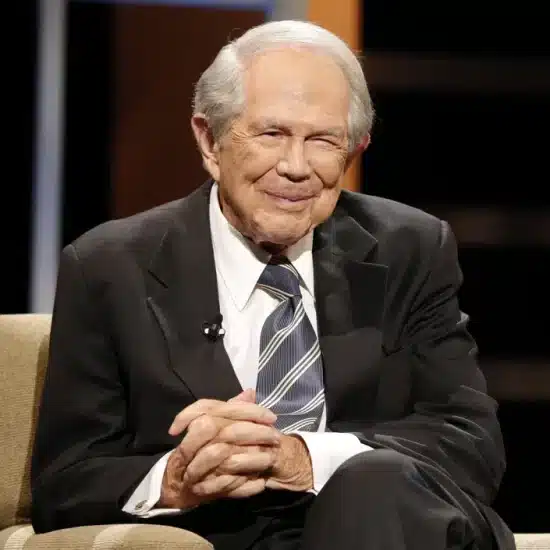

In this Feb. 24, 2016, file photo, Rev. Pat Robertson listens as Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump speaks at Regent University in Virginia Beach, Virginia. (Steve Helber/Associated Press)

Moments like these embarrassed his fellow Christians and marginalized the once-estimable political power Robertson wielded, consigning Robertson to the role of what one megachurch pastor called “the crazy uncle in the evangelical attic.”

But the right-wing conservative could also surprise his viewers. Once, he invited the Rev. Al Sharpton to the couch on The 700 Club to discuss climate change, agreeing that the issue is one that might bring the right and left together. In 2012, Robertson said that marijuana should be legalized.

Yet, any recollection of Robertson, who announced Friday his intention to retire as daily host of The 700 Club, must include his transformation of televangelism from hot, pulpit-pounding sermons to a cool format. With his avuncular, upbeat personality, Robertson, 91, changed the picture of what televangelism could be. His Tonight show-like The 700 Club featured conversational talk and couch interviews, interspersed with entertainment. The model was later adopted by Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker on their PTL (“Praise the Lord”) network and Paul and Jan Crouch on their Trinity Broadcasting Network.

Over the years, five presidents, both Democrats and Republicans, appeared on the show, along with numerous world leaders and musical artists.

“After, I think, 54 years of hosting the program, I thank God for everyone that’s been involved and I want to thank all of you,” he told viewers on Friday, adding, “It’s been a great run.”

His son, Gordon Robertson, who will replace him on the flagship program, released a statement saying, “‘Good and faithful’ doesn’t even begin to describe my father’s service to CBN for 60 years. His legacy and the example of his prayer life will continue to lead The 700 Club in the years to come.”

But his CBN platform was much more than good television. Founding the Christian Broadcasting Network in 1961, the first Christian network in the United States, he shepherded his flock of white evangelicals to a position of unprecedented political influence within the Republican Party.

In 1987, Robertson, a Yale-educated lawyer, a Marine officer veteran and the son of a U.S. senator from Virginia, leveraged his fame into direct political action, something earlier Christian fundamentalists had shunned. That year he formed the Christian Coalition, later joined by Ralph Reed, the telegenic political strategist. Soon, other evangelical leaders, like the Rev. Jerry Falwell, jumped on their own electoral bandwagons.

Robertson’s personal political high point came in 1988, when he ran for the Republican nomination for president, finishing third in the Iowa primary, behind Bob Dole and George H.W. Bush. In the campaign he claimed, without proof, that the Soviets were hiding missiles in Cuba.

Two years later, in 1990, the Christian coalition introduced ostensibly nonpartisan Christian voter guides, also called “Christian score cards,” handed out at conservative churches or placed on windshields in church parking lots.

“He was very smart,” said Frances Fitzgerald, author of The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America. “He turned his presidential campaign into this notion of organizing from the community base up. It’s what people have been doing ever since. You can’t always do it from a religion platform.”

He also wrote 20 books and founded Regent University, located across the street from CBN studios and headquarters in Virginia Beach, and the American Center for Law and Justice, a Christian activist organization led by sometime Trump lawyer Jay Sekulow.

Robertson’s firm support of former President Trump may well be the last memorable moment of his on-air career. After insisting for weeks that Trump had won, only to be cheated out of office by fraud, Robertson endorsed the Jan. 6 pro-Trump gathering at the Capitol in the run-up to the rally. After it proved to be a riotous attempted insurrection, Robertson stayed off The 700 Club for a week. When he returned, he acknowledged Biden’s victory.

But Robertson’s staying power — which necessarily included overcoming embarrassing moments — is an essential part of his legacy.

“When other well-known ministries fizzled for a variety of reasons, he maintained a ministry that was respected because of his moral and spiritual consistency,” said the Rev. Jim Henry of Orlando, a former president of the Southern Baptist Convention, in an interview with RNS. “He finished well. He finished strong, and I join with a host of others in saluting this man of faith.”

But other prominent evangelical voices said his legacy was tainted by his more outlandish comments.

“Pat Roberson’s ministry should not be judged by a single quote that offends,” said Richard Cizik, president of the New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good. “The problem is the sum of the parts. After putting televangelism on the map, Robertson devolved to an enfant terrible on progressive social movements, from the environment to women’s rights and race relations. In doing so he became more of a target for humor than any preacher would want.”

Some of his critics go beyond his ability to gaffe his way into the headlines. One group dubbed him “the Apostle of Hate” for his longtime opposition to LGBTQ rights.

“Pat Robertson contributed greatly to some of the worst trends in American Christianity over the last forty years,” said the Rev. David P. Gushee, distinguished university professor of Christian ethics at Mercer University. “These included the fusion of conservative white Protestantism with the Republican Party, the use and abuse of supernaturalist Christianity to offer spurious and unhelpful interpretations of historical events and the development of a conservative Christian media empire that made money and gained power in the process of making everyday Christians less thoughtful contributors to American life.”

Lisa Sharon Harper, president and founder of Freedom Road and author of the forthcoming Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World — And How to Repair It All, said Robertson had to answer for his racial message. “He has been a dreamer and a builder,” said Harper. “Unfortunately, for people of color and for the post-colonizing majority church in the world, Robertson’s dreams were awash with the protection and retention of white male domination; in church life, in public space and in pink-knuckled politics.”

In the end history will likely tip its hat to Robertson’s skill at drawing the attention of the country to the views of White evangelicals. What he did with that attention will be judged more harshly.

“Pat Robertson had enough religious savvy to get on a national stage and enough outrageous proclamations to keep blowing up his chances for success outside his religious realm,” said the Rev. Joel C. Hunter, a former megachurch pastor who now heads the Parable Foundation. “From his failed attempt to become president, to claiming to divert Hurricane Gloria with prayer from his TV studio couch — protecting his headquarters but causing millions of damages and eight deaths up the coast — Robertson had a talent for gaining power, resulting in social good through his ministry, but also in political divisiveness and cynicism outside his spiritual audience.”

Said Fitzgerald: “He was pretty much always a crazy uncle, except when he was running for president.”