The most destructive aspect of the American ethos is that we have developed a non-repentant state of mind. Isaiah must have seen us coming across the ages: “Oh, rebellious children, says the Lord, who carry out a plan, but not mine, who make an alliance, but against my will, adding sin to sin.” Many Americans revel in being anti-government, anti-vaxxers, anti-maskers, anti-climate change. Often, we say, the evidence doesn’t matter. Who cares about evidence and facts in the post-truth age?

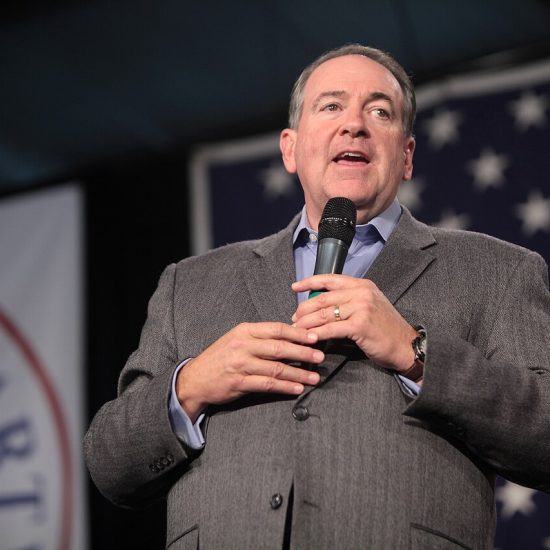

Rodney Kennedy

But why does this denial exist? Part of the answer may be philosophical: “We live at a point in history at which the demand for individual freedom has never been stronger – or more potentially dangerous.” In the 1960s people said, “I don’t care if smoking causes cancer, I am going to smoke till I die.” “Don’t tell me to ‘buckle up for safety.’” Such ideas would have been laughed out of the room until a few decades ago, but now it passes for common sense even though it threatens to thwart actions to prevent the destruction of human life.

What if we are merely anti-repenters?

The overwhelming majority of evangelicals are followers of the most famous anti-repenter in the nation: Donald J. Trump. President Trump famously insisted that he didn’t need to repent. Trump said he “likes to work where he doesn’t have to ask forgiveness.” Trump didn’t just reset the boundaries of evangelical faith – he upended an entire movement built on the need for repentance.

To repent means to turn and to change the mind. Repentance is an emotional and mental experience. We currently don’t see any reason for repentance. God takes care of God’s business, and we take care of our business. We don’t bother God and God doesn’t bother us. We are pretty much convinced by Voltaire’s declaration that “God forgives because it’s his business.”

In a stunning move of irony, instead of repenting, many Americans have this built-in desire to return to a state of innocence. The irony of a people who are supposed to be going forward, following Jesus, and we are inebriated with the desire to go back. Back we cry, “Back to the slave pots of Egypt.” “Back to the good old days.” “Back to the 1950s.” Jeremiah decried: “In the stubbornness of their evil will, they looked backward rather than forward.” Most of all, there’s the deep desire to go back to the Garden of Eden. The train going back to Eden stalled out and stopped in the ancient ruins of a disgraced city. That’s the place where God confused the language of all the earth and gave it forever the place name of Babel.

And as I listen to the way we have turned our nation into a Kingdom of Babel, I am convinced that we are not in the mood for gentleness or wisdom. Babel is social media, twenty-four-hour talk radio, television “opinionators,” network news, television evangelists, politicians, and a plethora of others. Our long stay in the land of Babel has been dangerously self-deceptive because it has convinced us that we are right and the others are wrong. We are righteous and the others are wicked. This is the true nature of an unrepentant cultural mindset: “Who do you think you are to tell me to repent?” The anti- crowd trumpets a refusal to be bound by anything, not even truth itself. How odd that evangelical Christians are now heralding the worst tendencies of post-modern, post-truth culture.

Luis Morera / Unsplash

In post-modern, post-truth Babel, we have freedom from truth. Untethered from truth, we make it up as we go. I believe that the original post-truth takes place in the rhetoric of the talking snake. “Did God say, ‘You shall not eat from any tree in the garden?’” Suspicion and mistrust are implanted in Eve’s mind. Then the BIG lie: “You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” The talking snake was a slick rhetorician using the trope of paralipsis: “I’m not saying God is a liar, I’m just saying.”

Eve fell for the BIG lie. After all, Eve knew the truth. She repeats the truth to the snake: “We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden; but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree that is in the middle of the garden, nor shall you touch it, or you shall die.’” When you know the truth but refuse the truth, you are in ultimate danger. Eve gets the offer of ultimate freedom, a licentious freedom of thought outside of the commands of God. She rejects the truth for the promise of not being bound by the possibility of death.

Almost everyone feels the world is spiraling out of control. We are no longer in charge and feel threatened by every movement. People think that everything they have been taught, everything they held dear, is being ripped from their hearts and they are not going to take it anymore. This is the spirit of the unrepentant. Everything wrong is somebody else’s fault. Americans have become the world’s most expert critics and with our “dipped in vitriol” opinions, we are not bashful about telling others how the cow eats the cabbage.

Like a hurricane sweeping across the land, the anger, fear, confusion, suspicion, mistrust pile up at the front steps of our minds each morning. If we hear something from our side of the great divide, we swallow it whole. If we read something that disagrees with our side, we fact-check it again and again. We are not a gentle, well-mannered people.

At some level, we all know that the evidence of Scripture – from the Law to the Gospel, from the prophets to Paul – goes against our violent, angry, unrepentant age. “Who is wise and understanding among you? Show by your good life that your works are done with gentleness born of wisdom.” What a novel idea for a culture far removed from the spirit of gentleness. Our gatherings are more like a professional wrestling arena than a church meeting. Yet, the idea that the more wisdom we acquire, the gentler we will become with others, deserves a fair hearing.

Paul Griffiths, in Intellectual Appetite: A Theological Grammar, talks about curiosity. As a scholar, I tend to think curiosity is a commendable virtue. I even encourage my students to develop curiosity. Griffiths notes that curiosity was once thought to be a vice. Curiosity was considered a form of love, by which the knower could have superior knowledge, more knowledge than others. They were curious for new knowledge so they could have control over that which they knew and power over those lacking such knowledge. Griffiths defines curiosity as an “appetite for the ownership of new knowledge.” Curiosity can become a form of intellectual greed and implant in the mind an insatiable desire to always want more knowledge.

Griffiths says that we should develop studiousness because it is a loving participation in knowledge as a gift to be shared. Instead of knowledge being a possession to maintain control and appear smarter than others, in a studious person knowledge is a participatory intimacy. This intimacy is “driven by wonder and riven by lament.” What we do with our knowledge is make it available to others because it doesn’t belong to us. We are sharing the knowledge that belongs only to God and it was God’s before we had a use for it or even knew anything about it. True knowledge is knowing that God loved us before we loved God.

A studious person has wisdom and shares it with others. And this is done with a gentle spirit. Instead of arguments to be won, there is a sharing of Christ and the gospel. Instead of needing to be right, there is a willingness to give away what we have to others. Rather than being offended when others disagree, there is humility in knowing that all knowledge comes from God and returns to God and belongs to God.

An appeal to studiousness may not seem like much of a response to an unrepentant age, but a change of mind must start somewhere. Even if we are possessed by anger, resentment, and fear, through confession and repentance we can be forgiven. Forgiveness, however, requires repentance. A non-repentant culture that sees no need for repentance is between a rock and a hard place.

Rodney Kennedy has his M.Div. from New Orleans Theological Seminary and his Ph.D. in Rhetoric from Louisiana State University. The pastor of 7 Southern Baptist churches over the course of 20 years, he pastored the First Baptist Church of Dayton, Ohio – which is an American Baptist Church – for 13 years. He is currently professor of homiletics at Palmer Theological Seminary, and interim pastor of Emmanuel Friedens Federated Church, Schenectady, New York. His sixth book – The Immaculate Mistake: How Evangelicals Gave Birth to Donald Trump – is now out from Wipf and Stock (Cascades).