This September marked a year since then-President Donald Trump enacted two executive orders to ban federal trainings involving critical race theory, white privilege, or any “sex or race-based ideologies” that did not match Trump’s idea of “patriotic education.” Technically, CRT is a method of analysis to interrogate and describe systemic, or widespread and multi-generational, racial discrimination within primarily the legal system. In practice, opponents use CRT as a fear-mongering label to target a wide array of topics and issues connected to race and gender, especially Black history.

Laura Levens

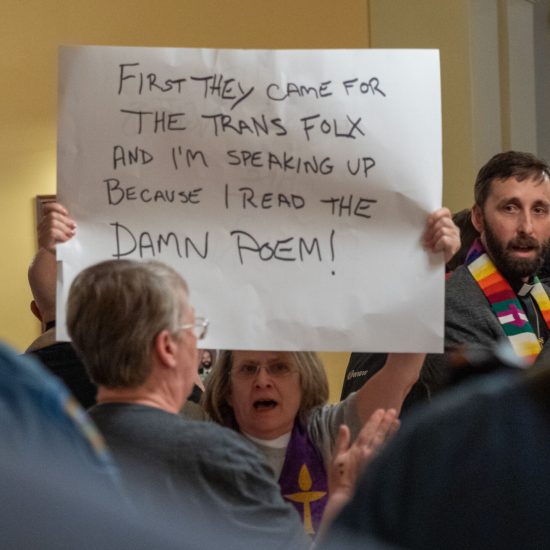

Over the past year, CRT-opposition and subsequent bans and restrictions have ballooned into a fever pitch in several church denominations and in American civil society at large. In December 2020, Southern Baptist seminary presidents effectively banned CRT, intersectionality (a method of analysis looking at both race and gender), and other critical theories in all Southern Baptist seminary classrooms. By August 2021, twelve state governments have passed laws greatly restricting parameters within which race, racism, and historical events can be discussed in the classroom.

History departments and history curriculums are directly affected because CRT-opponents in both American politics and the church are pushing their own presumptions about the very purpose of history for church and society. Political CRT-opponents who propose bans against diversity training and racial discussions in the classroom often support their laws with a precariously-selective view that historical education should ultimately increase patriotic loyalty.

When conservative Christians oppose CRT, they exhibit a second precariously-narrow view that Christian history should ultimately increase belief in the victory of Christ and the message of individual salvation. For example, Southwestern Theological Seminary President Adam Greenway claimed he was upholding Baptist Faith and Message Article 15 on “the regeneration of the individual by the saving grace of God in Jesus Christ” as foundation for any “means and methods used for the improvement of society.” Greenway maintained that CRT rejects the gospel upheld in Article 15, but theories like CRT are methodical tools to analyze institutional systems and social groups over time. By that logic, these presidents could limit the teaching of historical events and movements by their ability to validate the theology of individual salvation.

Furthermore, when Christian leaders prioritize and isolate the individual person as the only measure by which to count salvation and describe redemption, they practice history as if one individual story, predominantly told from a White heteronormative perspective, can explain the whole.

Anthony Garand / Unsplash

This is why the Southern Baptist Convention has long used a person like Lottie Moon, and now Adoniram Judson with the changing of the gavel, to stand for what they believe to be the exceptional legacy and expansion of the denomination across the United States and around the world. The actual histories of Moon and Judson — their interactions, their openness to other cultural worldviews, their failures, and the ways American Christians failed them — are reshaped to affirm the overarching greatness of the SBC.

When these two narrow purposes for history combine into the historical outlook of an exceptional country made victorious by an exceptional Christian faith for individuals, the result is Christian Nationalism. This is why I take historians like Dr. Jemar Tisby (The Color of Compromise and How to Fight Racism) and Dr. Anthea Butler (White Evangelical Racism) seriously when they point out the direct links between White evangelical denominations, CRT opposition, Christian Nationalism, and White supremacy. When Butler, Tisby, and other American historical scholars write and teach, they promote critical thinking about Black history, immigration, mass incarceration, and more. They see the link between belief about history’s purpose and the effect upon people’s lives.

The purpose of history is not for telling tales of victorious nations and churches. That is called propaganda. The purpose of history is a commitment to deal with the complexities of the past, so that we might understand and address present realities with wisdom. When this is our shared purpose, we are free to expand our lenses for learning history. We can engage in history with empathy, clarity, and the rigorous demand to face the whole of the past, especially violent atrocities and oppressions that have been long denied. We can confront mythologies of American exceptionalism, Christian superiority, and Christian Nationalism. Who could we learn from if there was no ultimatum to ensure America or Christianity emerges triumphant before the story even began?

Laura Levens is an assistant professor of Christian mission at the Baptist Seminary of Kentucky. She is currently working on a book about the mission theology and practice of Ann Hasseltine Judson.