(RNS) — Owen Strachan has a message for his fellow evangelicals. They can follow Jesus, or they can be woke. But they can’t do both.

Using traditional media and on Twitter, Strachan, a seminary professor in Conway, Arkansas, has become a leading evangelical Christian voice in the “woke wars” that have been turning school boards, television screens and church pews into political battlefields. In conservative circles “wokeness,” a term invented by Black activists to refer to social injustice awareness, is now shorthand for “liberals ruining America.”

The 40-year-old Strachan maintains that being woke is worse: It is heretical.

In Christianity and Wokeness: How the Social Justice Movement Is Hijacking the Gospel — and the Way to Stop It, a book Strachan published last year, he recommended excommunication for those who “do not repent of teaching CRT, wokeness, and intersectionality.”

Since at least the George Floyd summer of marches and demonstrations against police killings of unarmed Black men, evangelical leaders have been echoing the broader alarm heard in last fall’s political campaigns about the divisions they say that wokeness, critical race theory, and other social justice ideas visit on American society.

But the threat to conservative Christians, these leaders say, cuts deeper: Wokeness and its underlying theories deny evangelical theology, which holds that personal sin leads to evil and that repentance and acceptance of Jesus’s grace is the way out.

In an interview with Religion News Service, Strachan explained further that wokeness undermines the unity of churches by emphasizing racial and ethnic differences. The gospel, he said, erases such distinctions, while wokeness pits people against each other.

“When you embrace a system like critical race theory or intersectionality that teaches you that people who are in the majority basically are in the wrong — so, for example, that White people by virtue of being part of the White power bloc have privilege, have responsibility, honestly, when we’re not speaking politely, have complicity in oppression — that warps the gospel,” he said. “That is not a gospel conviction. That’s not taught in Scripture. People who are from the upper tiers of society in the Book of Acts are not condemned for being part of the upper tier of society.”

Strachan also dismissed the idea of systemic racism, or any claim that race plays a role in the inequities present in American culture. He also dismissed the idea of reparations for past racism and took issue with use of the word “repent” in discussions about America’s racial history, saying the Bible does not hold people accountable for sins of the past.

“This is the greatest threat to the gospel in 100 years. It’s the new social gospel,” he explained, referring to progressive Christians’ call in the early 1900s to live among and improve the lives of the urban poor, which evangelicals of the time rejected.

Anthea Butler, a University of Pennsylvania religion scholar and author of White Evangelical Racism, said White evangelical leaders have long faced a dilemma when it comes to race: They want to bring people of all sorts to the church without disrupting the status quo outside the church. The legendary evangelist Billy Graham desegregated his crusades during the civil rights era of the 1950s and ’60s, Butler said, while also claiming that “extremists are going too fast.” Jesus, he said, would make racism “obsolete.”

“On the one hand, evangelicals wanted souls to be saved,” Butler writes in her book. “On the other, they wanted everyone to stay in their places.”

In an interview with RNS, Butler said those two goals are no longer compatible. Evangelicals, threatened by the country’s changing demographics, are fearful of becoming a minority in their own big tent if they pursue their historic aim to spread Christianity. The racial reckoning in the wake of Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police, meanwhile, has undermined the myths that sustained their power, she said, leading to pushback against calls for racial justice.

“They believe it is an existential threat to their nostalgia about America,” Butler said.

White evangelicals’ fear of being overtaken by other groups makes their claims of colorblindness hollow, said Butler. While Strachan and other anti-woke voices often point to the legacy of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., saying they want to judge people by “the content of their character” — not the color of their skin — they also reprise civil rights era claims that calls for racial justice are a disguised socialist plot.

“It’s the same arguments recycled in a new form,” Butler said.

But you don’t have to be White to mistrust wokeness.

James Pittman, pastor of the multiethnic New Hope Community Church in the Chicago suburb of Palatine, Illinois, has both theological and pragmatic concerns about CRT. Much like Strachan, Pittman, who is Black and conservative, argues that CRT assigns blame and guilt based on people’s ancestry or skin color — not on their actions, something that he says the Bible does not do.

But Pittman also worries that discussions about CRT and systemic racism overshadow other systemic problems in American culture — in particular, education inequality. He’s a critic of the Chicago school system, one of the nation’s largest, where Black students on the city’s south and west sides have often struggled.

“These kids are stuck in a machine,” Pittman said. “They keep putting kids in failing schools.”

Pittman, a graduate of Howard University and Trinity International University, pointed to the impact that education had on his own life. A New Orleans native, he attended St. Augustine High School, a Catholic-run predominantly Black preparatory school there for young men. That school gave him a great education and a sense of pride in who he is.

“The culture was, I’m going to teach you to read and write and to not play second fiddle to anyone,” he said. “It’s more than ABCs and 123s — it is a reaffirming of who you are and not to look at the color of your skin as a negative.”

He chafes at the idea that White Supremacy could hold him down.

“I never believed in White Supremacy,” he said. “I never thought that I was inferior because I am Black.”

There are some who see evangelicals’ pushback against racial and social justice as more political than theological, an effect of evangelicals’ adoption of the Republican Party to see their faith agenda reflected in U.S. law. The identities have merged, and as wokeness has become the calling card of the Democratic left, evangelicals oppose it as Republican loyalists.

Samuel L. Perry, associate professor of sociology at the University of Oklahoma, is one of those who say that the evangelical church’s war against wokeness shows that evangelicals are defined more by their politics than their faith. He pointed to data from Pew Research Center showing the growing number of people who identified as White evangelicals during the Trump era, including some who had been unaffiliated.

“I think the whole identity is being hollowed out by the culture war,” he said. “White evangelical is becoming this empty category that really just means friendly to religion and really conservative.”

In a 2020 speech to the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee, then-SBC President J.D. Greear, a North Carolina megachurch pastor, warned of the clash between the evangelical movement’s religious ideals and its quest for political influence.

“We are not, at our core, a political activism group,” he told fellow SBC leaders. “We love our country, but God has not called us to save America — he’s called us to build the church and spread the gospel and that is our primary mission.”

Greear was addressing division in the nation’s largest Protestant denomination over issues such as social justice and CRT, which have led critics to claim SBC leaders are woke and liberal. After the denomination’s seminaries declared that CRT was incompatible with the SBC statement of faith, several high-profile Black churches left in protest. Strachan, who once led the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, which is based at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and taught at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri, left the denomination in part because he believes it has become too woke.

But the debates over “wokeness” and CRT aren’t really even about politics per se, Perry argues. Instead, they are debates over group identity and power. He pointed to the work of Lilliana Mason, a John Hopkins University political science professor, who writes about “affective polarization” — the idea that Americans are divided not by policy, but by how they feel about people who are different from them.

Americans are polarized around what Mason calls “mega-identities” — where their religious, political, social beliefs all merge. Those identities compete with each other, Mason argues, often driving people to political action out of dislike for those with other identities.

Labeling people as “woke” is not a statement about people’s ideas about police killings or race in general, Perry said. It is designed to trigger an emotional response, telling evangelicals and other conservatives that they are not to be trusted.

“It’s ultimately a game of identifying boundaries,” said Perry.

But prying theology, politics and identity apart may be impossible. In his book, Strachan says that works on racism in the church, such as The Color of Compromise by Jemar Tisby, Prophetic Lament by Soong-Chan Rah, or Woke Church by Eric Mason, are signs that wokeness has supplanted Christian theology. He is particularly critical of Divided by Faith, a 2000 book by researchers Michael Emerson and Christian Smith, which documented the racial divides among Christians who share similar beliefs.

Emerson, chair of the sociology department at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said he used to think White Christians and Christians of color were interpreting the same faith in different ways. Now he believes that the two groups are practicing different faiths with different beliefs, with White Christians holding to a version of the faith that supports their political and social power.

“It is very theological at the core — but a different faith that prioritizes very different things,” he said. “It prioritizes being OK with privilege, prioritizes racial tribe power and position and individualism — a lot of things that just wouldn’t jibe with the traditional interpretation of the biblical text.”

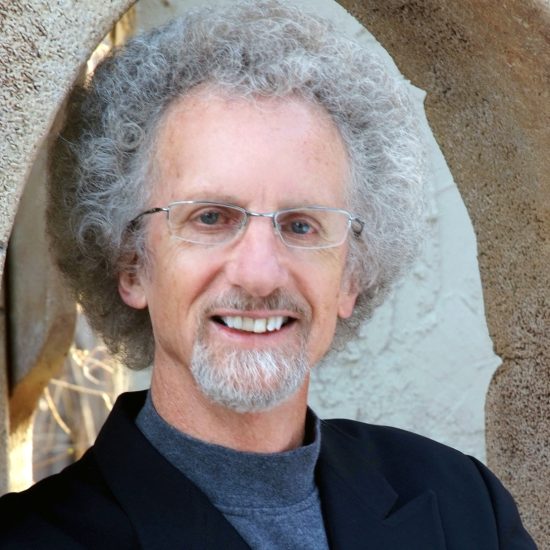

Glenn Bracey (left) and Michael Emerson present during Mosaix Global Network’s Multiethnic Church Conference on Nov. 6, 2019, in Keller, Texas. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

Recently Emerson presented data from a forthcoming book he is writing with colleague Glenn Bracey, The Grand Betrayal: The Agonizing Story of Religion, Race, and Rejection in American Life. The co-authors looked at data on what they call “practicing Christians” — Americans who say they are Christian, say their faith is very important to them and attend church at least monthly. They found wide disparities in how Christians from different racial groups view race relations in the United States.

In the summer of 2019, researchers asked Americans if they thought the country had a race problem. Three-quarters (78%) of practicing Black Christians said yes, compared with just over a third (38%) of White practicing Christians. A year later, in late summer 2020, researchers asked the same question and found an even starker divide, with 87% of practicing Black Christians agreeing, compared with 30% of practicing White Christians.

When asked if Americans of color are treated less fairly on a range of issues — hiring, pay, promotions, housing, mortgages, and the criminal justice system — the majority of Americans of color, whether of Asian, Hispanic or Black heritage, agreed, as did half of non-Christian Americans.

“One group stands alone: White practicing Christians, where about two-thirds disagreed,” according to a presentation Emerson gave to a gathering of Protestant pastors in January.

He said White Christians who reject stories of the country’s racial divides are intentionally ignoring the world around them.

“It isn’t a lack of understanding so much as it’s what we call the epistemology of ignorance— willful lack of understanding,” he said. “It’s an investment to not understand, that I will not hear what others are saying, because it doesn’t benefit the way I interpret the world.”

Not all evangelicals are comfortable with that willful ignorance, and some are concerned that the full-throated rejection of wokeness is becoming a conversation within evangelicalism that will eventually divide the conservative church.

Erik Reed, pastor of The Journey Church in Lebanon, Tennessee, said he first began reading about CRT as a graduate student at Vanderbilt Divinity School, where he attended before finishing his degree at a Southern Baptist seminary. Reed said systemic racism is a real problem in society, something his belief in the Calvinist doctrine of “total depravity” — the idea that humans are inherently corrupted by sin — helps explain.

“I believe we’re capable of terrible things,” he said. “It’s silly to deny atrocities, it’s silly to deny oppression when you believe man is sinful and capable of awful things.”

Reed said the conversations he once heard at Vanderbilt, known for having a more progressive view of theology, are now taking place among evangelicals. He believes unjust systems need to be fixed. But he also sees the divides in American culture as rooted in sin, something a social theory can’t undo. He said that online debates about CRT and “wokeness” reflect what’s going on in church pews and that those debates aren’t going away.

“I am finding there are a lot of people who profess the same core convictions but they seem to be heading in very divergent directions,” he said.