For the White House chief of staff, the stakes could not have been higher.

“This is a fight of good versus evil,” Mark Meadows, the former top aide to then-President Trump explained. “Evil always looks like the victor until the King of Kings triumphs. Do not grow weary in well doing. The fight continues. I have staked my career on it. Well at least my time in DC on it.”

He applied that apocalyptic language not to an existential foreign threat like Russia threatening nuclear war nor to a deadly global pandemic like COVID-19. The “evil” he feared — and that only the “King of Kings” could help defeat — was Joe Biden, a fellow citizen and the rightful winner of a free and fair presidential election.

Meadows’s texting buddy was Virginia “Ginni” Thomas, a prominent conservative activist and wife of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. News reports last week revealed Ginni Thomas worked to overturn the election results while Justice Thomas penned dissents in cases Trump’s camp lost as they sought to undermine the election and the investigation into the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection.

In a series of anxiety-filled texts, Ginni Thomas reached out to Meadows after the election in conspiracy-laden terms: “Help This Great President stand firm, Mark!!! … The majority knows Biden and the Left is attempting the greatest Heist of our History.”

Her solution to Meadows for saving the Republic was to make Sidney Powell “the lead and the face” of Trump’s legal response. Powell, of course, falsely and prominently claimed the election was stolen from Trump through a plot involving the Venezuelan government, an unidentified server in Germany, and electronic voting machine irregularities (which all makes Rudy Giulani’s running hair dye and press conference outside a landscaping center almost look sane by comparison). Her alarmist rhetoric and outlandish legal filings resulted in her facing judicial sanction, potential disbarment, and a defamation lawsuit.

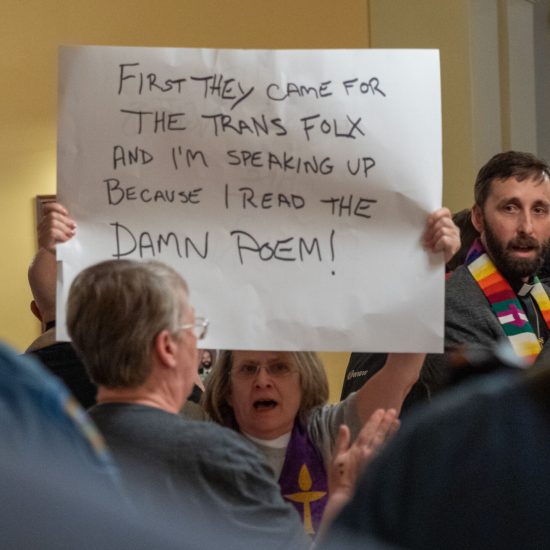

Since news broke of Thomas’s efforts to influence both the White House and Congress, attention has understandably been focused on whether she’ll be asked to testify before the House committee investigating the Capitol insurrection and whether her husband should recuse himself from cases related to the events of Jan. 6. Largely ignored in the coverage is the religious overtones of the exchange.

“We haven’t paid enough attention to the role of right-wing Christian Nationalism in driving Trump’s effort to destroy our political order, and in the abandonment of democracy among some on the right more broadly,” wrote Washington Post columnist Greg Sargent, one of the few to take notice (though if he’d been reading A Public Witness or listening to Dangerous Dogma he would have realized the problem much sooner).

Ginni Thomas and Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas arrive at the White House for a State Dinner with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and President Donald Trump on Sept. 20, 2019. (Patrick Semansky/Associated Press)

The text exchange between Thomas and Meadows reveals how fringe ideas were mainstreamed throughout the Trump Administration and especially at its ignoble end. They also show how key actors saw the unfolding events of a secular democracy in starkly religious terms.

“Think about the sickness of this,” exclaimed MSNBC host and former GOP Congressman Joe Scarborough in reference to the language employed by Meadows. “He summons the name of Jesus Christ for his help in overturning American democracy!”

In this edition of A Public Witness, we read the texts of messianic and apocalyptic ideas animating parts of the Trumpian movement. Then we take advantage of your unlimited data to warn about the danger of half-baked religious prophecies masked as partisan politics.

Messianic Expectations

Donald Trump stood behind the podium at the 2016 Republican National Convention with a message both for the faithful gathered at his political coronation and the nation at large: “Nobody knows the system better than me. Which is why I alone can fix it.”

That appeal to personal greatness was out of step with the transcendental references, appeals to a common cause, and expressions of humility that usually characterize such addresses. But it also burst with irony given previous Republican criticisms about the man Trump hoped to replace in the White House.

In 2008, the presidential campaign of Sen. John McCain produced an adcalled “The One.” Drawing attention to the soaring rhetoric of Sen. Barack Obama, the McCain campaign depicted Obama as creating overinflated expectations to overcompensate for his relative inexperience. People needed to wake up and realize this self-proclaimed messiah was promising a salvation he couldn’t deliver. (Some saw a more devious intention to portray Obama as the antichrist.)

Whether accurate on Obama or not, the McCain campaign’s broader point was correct. Politicians are flawed, self-interested human beings like everyone else. Skepticism is the appropriate response when a public leader suggests they are uniquely capable of bringing about national redemption or single-handedly capable of delivering the country from its sins. For Christians, assigning messianic status to our favored candidates quickly morphs into idolatry.

Ginni Thomas seems to cross that line in texting Meadows: “You are the leader, with [President Trump] who is standing for America’s constitutional governance at the precipice.” As she perceived the fate of the nation hanging in the balance, she saw one person (aided by Meadows) who could fix it.

Trump regularly stoked such expectations. In August of 2019, he retweeted praise from an evangelical supporter who compared the president to “the King of Israel” and “the second coming of God.” (We also like supporters to say nice things about us on social media, but you don’t have to go that far.) Then while talking about enforcing tough trade policies towards China, Trump declared, “I am the Chosen One.”

All this put Trump’s evangelical supporters on the defensive. Robert Jeffress took to the radio to make clear that Trump “doesn’t see himself as the Messiah.” Even if the former president didn’t take himself that seriously, some of his supporters — including high-level elites — did. Energy Secretary Rick Perry gave Trump a pamphlet on the Israelite kings in the Old Testament and told Trump, “I want you to look at this. I want you to read it. I want you to, you know, absorb that you are here at this chosen time because God ordained it.” Other moments added to this messaging, including a controversial and violent photo op at a church that Meadows praised in his memoir.

Then-President Donald Trump holds a Bible outside St. John’s Church near the White House on June 1, 2020, after peaceful protesters were teargassed, including ministers on church property, so he could pose for the photo. (Patrick Semansky/Associated Press)

Meadows used to know better than to succumb to such hero worship. Or at least he offered a healthier perspective when talking to his home church — Community Bible Church in Highlands, North Carolina — early in his congressional career. Speaking during a Wednesday night service on July 1, 2015, he warned against confusing government with the purposes of the Church. His warnings, which followed on the Supreme Court legalizing same-sex marriage, portrayed the events in theological terms.

“What the Church can offer will never be duplicated by what the government can offer. And that’s the one that thing that we need to really realize is that a lot of people are looking to fill that void in a certain way,” Meadows said. “I don’t want you to get discouraged over a couple of Supreme Court rulings. I mean, let me just tell you, black robes do not define in the end how the final chapter is written. You know, God still reigns. He is still on the throne.”

However, warning signs can still be seen in Meadows back then as he espoused Christian Nationalist ideas about the founding of the nation that he mixed with a Christian persecution complex.

“It is a hostile environment for most Christians in Washington, D.C., without a doubt. You can be almost any other faith, other than being a Christian, and it’s okay,” Meadows claimed. “That’s really where Washington, D.C., is going, to make sure [society’s] secular. The real problem with that is that our whole foundation of government was set on a Judeo-Christian foundation. … We really have to find a way, I believe, to continue to show the undergirding of our Judeo-Christian values — and every law that is out there has some basis, some moral foundation.”

Five years later, Meadows sat at the pinnacle of power but still could not shake the siege mentality. The man who warned others against confusion had lost sight of what the Church can offer that the government cannot.

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

American Apocalypse

“We are living through what feels like the end of America,” Thomas texted Meadows on another occasion. Instead of seeing healthy competition between two political parties with different agendas, she saw a struggle between good and evil. To her, the wrong side winning was not an electoral defeat but an existential threat.

Such a worldview is more theological than political, drawn from biblical books and passages like Daniel and Revelation. As a genre they are defined by the communication of a secret knowledge that witnesses to what will be, despite the challenge of present circumstances.

“Apocalypses typically expect a divine intervention and a decisive judgment, in which God will destroy the ‘bad people.’ This way of thinking is dualistic in an over-simplified way, and it often encourages intolerance,” explainedJohn Collins, a biblical scholar at Yale Divinity School. “Also the violence of the judgment can be troubling. The violence is fantasized, and it can be a way of letting off steam without resorting to actual violence. But there is always a danger of slippage — thinking that if God is going to kill bad people, perhaps we should give him a helping hand.”

Those abstract fears became tragic realities on Jan. 6 when insurrectionists stormed the Capitol. Writing for Rolling Stone, Sarah Posner documented how the apocalyptic beliefs and rhetoric of the Christian Right helped inspire the tragedy. Alluding to hidden knowledge, an organizer of a December evangelical protest in D.C, that proved to be a forewarning to Jan. 6, claimed that “God can reveal all the election fraud and corruption that stole the election from [Trump].” Roger Stone confessed to the crowd his belief that God would intervene: “My faith is in Jesus Christ, and we will make America great again and we will stop the steal.”

Not to be outdone, notorious conspiracy theorist Alex Jones cast the fight in Christian terms before promising that Biden “will be removed, one way or another.” Jones later double-downed on his apocalyptic vision. Posner reported that at a Jan. 5 event he referred to the incoming president as a “slave of Satan” before stating that “things are going to be rough, things are going to get bad in the future.” Jones then reassured the crowd that “not everybody is going to make it, but that’s OK, because in the end, God will fulfill his destiny and will reward the righteous.”

Thus, when Thomas texted Meadows about “Fraud exposed and America saved,” it is hard not to hear apocalyptic echoes. This is more than a partisan advocating for a cause. It reflects a worldview where God intervenes to help the righteous, snuffing out evil and restoring the righteous.

Screengrab as Mark Meadows (right) speaks about politics and faith at Community Bible Church in Highlands, North Carolina, on July 1, 2015.

And this thinking goes beyond Thomas and Meadows. As PRRI polling last fall found, White evangelicals were “the only religious group among whom a majority believes the election was stolen.” A full 61% had bought into this debunked lost cause of Trump, with most instead blaming liberal activists as if it were some kind of false flag operation. And 25% of White evangelicals believe in QAnon conspiracies, outpacing the national rate of 17%. Mix that conspiratorial thinking with the belief that America has a special, divinely-chosen role to play in the world that’s threatened by efforts to make this no longer a “Christian nation,” and you get a combustible formula.

This is not just a fervent Christian Nationalism that conflates American identity with a certain brand of conservative Christianity. It’s an end times Christian Nationalism that sees democratic elections as an ultimate fight for the soul of the nation.

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

Perilous Prophecies

There’s more at play with the Meadows and Thomas texts than merely Christian Nationalism. As Paul A. Djupe, a political scientist at Denison University, noted in January, belief in prophecy is “the accelerant of American extreme politics” like Christian Nationalism.

“Prophetic Christian Nationalists support much more group extremism than those who do not believe either of those things,” he explained.

Djupe defined what he means about those with prophesy beliefs: “Prophecy beliefs entail that God’s power and thoughts are channeled through human beings to, for instance, tell the future and heal people. Prophetic religion enables at least two things: absolute certainty and completely flattened organizational structures — anyone can lead.” Data on American beliefs show this belief in prophecy isn’t limited just to evangelicals or Pentecostals.

This sense of divine certainty can become particularly dangerous when mixed with a Christian Nationalistic view that one party is trying to take away religious liberty and persecute Christians through impeaching Trump or “stealing” elections. Put together, those beliefs make one more likely, Djupe wrote, to believe “extreme measures would not be off the table.” Like supporting an insurrection to overthrow our democracy. As Djupe found, prophetic Christian Nationalists are “considerably more supportive” of the Jan. 6 insurrection than even other Christian Nationalists.

“It seems obvious that belief in prophetic religion, which is widespread in American religion, bestows a level of certainty and righteousness that can propel projects forward with no guardrails,” he added. “It just so happens that prophetic Christian Nationalists are common and are likely to rally behind extreme groups on their side. It is no surprise that they have much greater support for the insurrection and groups like those involved on that day — this is not going away any time soon.”

Women who are part of the pro-Trump crowd outside the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, hold a banner declaring, “God Chose Trump to Save USA.” (Tyler Merbler/Creative Commons)

In light of his research, we asked Djupe about the Meadows-Thomas texts. He told us that “many actors have been arguing as if the final battle between good and evil is imminent through the mapping of conditions similar to when Revelation was written — Christians under siege, persecuted by the Roman and other empires.”

“In this case, the claim is that Democrats will strip Christians of their freedoms,” he added. “When [Thomas] urges Meadows to ‘release the Kraken’ and argues that the ‘Biden crime family’ will be tried at ‘Gitmo,’ she is tacitly admitting that forces of evil are active in the world and embodied in the Democratic Party. Far from turning to wait for the next world, apocalyptic believers see themselves as soldiers with ‘the armor of God,’ embroiled in a battle to save the world from demonic forces.”

But there’s also something different about this modern political version of the end times story.

“It’s important to note that the modern instance of apocalyptic thinking and communicating appears stripped of its theological baggage. There are no mentions of Daniel and Revelation, no many-headed beasts, no dispensations,” Djupe told us. “And what makes it especially plausible is that so many Americans believe in prophecy — that God is in control and communicates directly with humans. We see this way of thinking throughout the Trump Administration (see Paula White), and especially at the end of it in the Jan. 6 insurrection, when people stormed the Capitol to take back America for God.”

All this is an ominous sign for committed Christians. Such nationalistic visions not only warp the democracy in which we live, they also disfigure the faith we profess. Our testimony about God reigning as the Ancient of Days is distorted when we demand people bow before our political agendas.

We’ve learned that a White House chief of staff and the activist spouse of a Supreme Court justice traded in the very sins that the book of Revelation denounces: mistaking temporal power for the everlasting desires of God. Bad theology about the end times helped fuel the attempt at democratic armageddon.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood