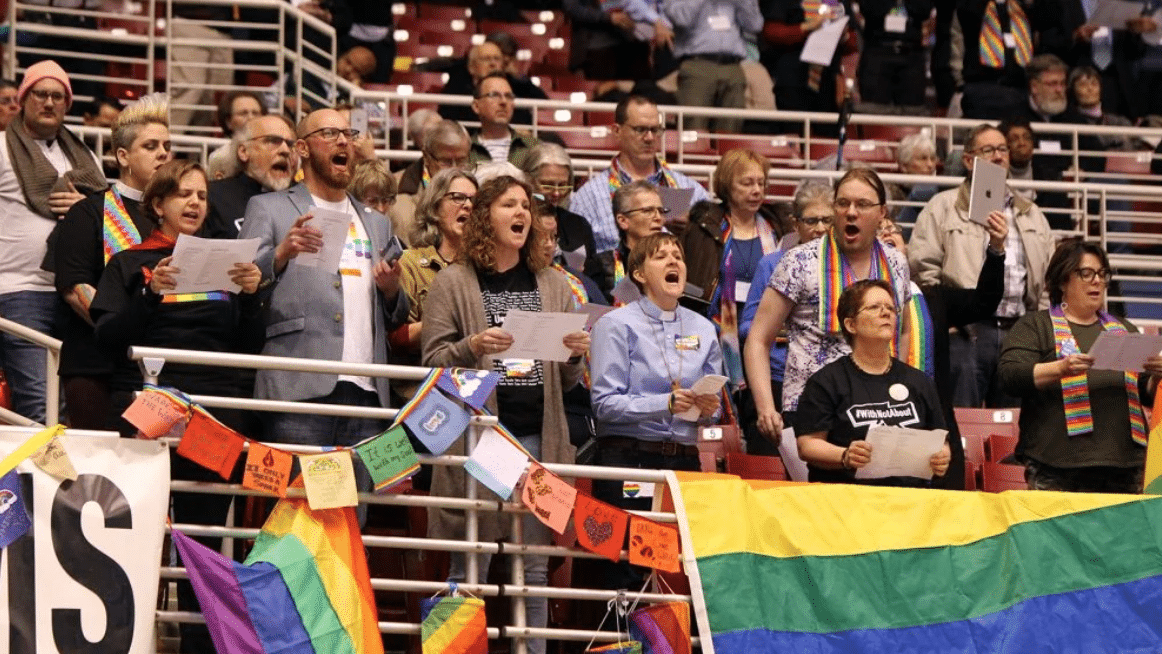

LGBTQ advocates react to the Traditional Plan being adopted at the special session of the UMC General Conference on Feb. 26, 2019, in St. Louis. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

(RNS) — It was the thing that was supposed to save the United Methodist Church.

The Protocol of Reconciliation & Grace Through Separation, brokered by 16 United Methodist bishops and advocacy group leaders from across theological divides, outlined a plan to split the mainline Protestant denomination over its disagreement about the ordination and marriage of LGBTQ United Methodists.

But before delegates to the General Conference, the denomination’s global decision-making body, could vote on the widely endorsed protocol, so-called traditionalists went ahead and launched a new denomination, the Global Methodist Church.

And, most recently, several representatives of groups identifying as centrist and progressive announced they no longer supported the protocol.

While legislation to enact the plan still likely will be considered at the next General Conference meeting, wavering support for the protocol leaves the United Methodist Church either imagining a new way forward or plunging into chaos, depending on whom you ask.

So what happened?

Mainly, bishops and advocacy group leaders say, too much time went by. Because of COVID-related delays to the General Conference meeting, four years will have passed by the time delegates finally can vote on the plan they negotiated.

“There’s a lot that’s happened since that protocol was signed, and the context really has changed,” said Bishop Thomas Bickerton of the New York Annual Conference, who recently became president of the denomination’s Council of Bishops.

“We’re sad about these departures that are happening, but to think that the protocol is going to be the great solution, I don’t know that it will, because it’s in the hands of these delegates who are going to amend it and change it and make it what they want.”

The dividing conflict within the United Methodists Church — mainly the question of LGBTQ inclusion and affirmation — goes back to 1972, when the General Conference voted to add language to the denomination’s Book of Discipline declaring that “the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching.”

That language was revisited every four years at subsequent General Conference meetings until 2016, when delegates voted to hold a special session to finally settle the debate. At the 2019 special session, delegates narrowly voted to adopt what was known as the Traditional Plan, which upheld and strengthened language banning the ordination and marriage of LGBTQ United Methodists.

But the debate was hardly settled. Many LGBTQ United Methodists and their allies immediately vowed to resist and remain in the denomination.

Devastated by what he called the “poor witness” of the contentious special session, Bishop John Yambasu of Sierra Leone called a meeting of several bishops from outside the United States, as well as leaders from advocacy groups across traditionalist, centrist and progressive views.

In January 2020, that unofficial mediation group announced it had reached an agreement: The Protocol of Reconciliation & Grace Through Separation would allow traditionalist congregations and conferences to leave the United Methodist Church, taking with them their properties and $25 million to form a new Methodist denomination. The post-separation United Methodist Church would meet later to repeal language barring LGBTQ United Methodists from ordination and marriage.

Yambasu predicted “total disaster” if the protocol wasn’t approved at the 2020 General Conference.

But then, a deadly pandemic swept the globe, postponing the General Conference not once, but three times to 2024. Things started to come apart.

After the third postponement, some traditionalists, tired of waiting, announced they were launching the Global Methodist Church.

Earlier this month, four representatives of centrist and progressive advocacy groups and one clergyperson from the Philippines — all of whom had negotiated and signed the protocol — published a statement saying they “no longer in good faith” could support the plan or work toward its adoption by the General Conference.

The Protocol Response statement noted a lack of support from delegates, leaders outside the U.S. and members of the groups its signers represent.

“The overwhelming consensus among those with whom we spoke is that the once-promising Protocol Agreement no longer offers a viable path forward, particularly given the long delays, the changing circumstances within the United Methodist Church, and the formal launch of the Global Methodist Church in May of this year,” it reads.

There were other factors, too: Yambasu, the driving force behind the protocol, died in a car accident in August 2020, pointed out the Rev. Tom Berlin of Floris United Methodist Church in Herndon, Virginia, who represented centrist organizations in the protocol negotiations. The Rev. Junius B. Dotson, who negotiated on behalf of a number of centrist advocacy groups, died of cancer the following February.

Finances also had factored into the negotiations, Berlin said. Two and a half years into a pandemic that forced many churches online in its early days, he can’t say if the figures they considered remain valid.

And the denomination’s Judicial Council since has decided that annual conferences cannot unilaterally decide to leave the denomination.

“The protocol legislation is alive and well. What we did is we tried to help people understand we don’t think it’s got the support it once did, and we’re the authors of it. It’s not that I’m happy about that. It’s just that I think I have a responsibility of transparency to share with a larger church where people are at,” Berlin said.

Jan Lawrence, one of the signers of both the protocol and the Protocol Response statement, sees an opportunity to imagine something new.

The world is a different place than it was at the beginning of 2020, noted Lawrence, head of the LGBTQ-affirming Reconciling Ministries Network. Separation — one of the primary purposes of the protocol — already has started.

Everybody wants to avoid the bitterness of the 2019 special session, she said, which means “somebody’s got to come up with something new and what that new thing is.”

“The conversations haven’t gone far enough to really have a concept of what that might be, but by us walking away from the protocol, it gives room for those conversations to happen,” Lawrence said.

Not everybody is as optimistic. The Rev. Jay Therrell, who recently became president of the theologically conservative Wesleyan Covenant Association, sees a denomination in chaos.

Therrell said Wesleyan Covenant members were disappointed by the Protocol Response statement and still believe the protocol is the best way for Methodists to move forward. His predecessor — the Rev. Keith Boyette, who now heads the Global Methodist Church — had been part of protocol negotiations.

“To us, it feels as though they have chosen to make what is already a very difficult situation even more so,” Therrell said.

It’s “no secret” the Wesleyan Covenant Association is an “advocate for and an ally for theologically conservative churches to depart the United Methodist Church for the Global Methodist Church,” he said — that’s part of the updated mission it adopted at its meeting earlier this year. But the new president of the organization sees that working “in concert” with the protocol, which always had the creation of a new, traditionalist expression of Methodism as its goal.

Pulling support for the protocol now is “just another ploy to send the denomination deeper into chaos,” trapping traditionalist churches, according to Therrell.

“They say that they want a big tent, but the reality is they want a tent that is big enough to take money from theologically conservative churches but not honor our theology,” he said.

Bickerton, who was part of the protocol negotiations, said he’d place himself somewhere in between those two views.

“I don’t think that we’re in a state of chaos, but neither do I think that everything’s just fine,” the president of the Council of Bishops said.

The seven bishops who had been on the mediation team released their own statement after the Protocol Response that affirmed the work that had been done on the plan. But, Bickerton said, when bishops signed the protocol, they essentially turned it over to the General Conference to decide its fate.

“It’s legislation that’s in the hands of the delegates, and we trust that,” he said.

Bickerton isn’t sure what will come next for the United Methodist Church.

But, the bishop said, he hopes churches won’t wait to find out.

“I’m not willing to allow the denomination to be paralyzed until General Conference,” he said.

Even without the protocol, there already are provisions in place that allow churches to leave the denomination with their properties.

In addition to the Traditional Plan, the 2019 special session approved a measure allowing churches to disaffiliate from the denomination by Dec. 31, 2023, “for reasons of conscience” related to sexuality. Those churches must pay off any loans from their annual conferences, as well as two years of apportionments to the denomination and a share of what their conferences will owe retirees.

While some now argue it’s unfair, Bickerton said, he doesn’t think it’s unreasonable for congregations to meet their obligations to pastors, allowing them “to retire with dignity and some means to live through their retirement.”

Some churches took that step at their annual conference meetings this summer. The bishop is waiting for a count now that annual conference season has ended in the United States, but he said it seems that number is relatively small.

For instance, while Therrell has said more than 100 Florida churches plan to leave the United Methodist Church for the Global Methodist Church, Bishop Kenneth Carter, who leads the Florida and Western North Carolina conferences, confirmed to Religion News Service that only 14 disaffiliated at this summer’s Florida Annual Conference meeting.

Bickerton doesn’t want any churches to leave, he said, but knowing some will, he hopes to mitigate the upheaval.

Christians are called to make disciples of Christ, he said. Different denominations will do that in different ways. If United Methodists are focused instead on “our internal chaos,” he said, it won’t happen. There are needs that won’t be met, injustices that won’t be addressed.

While emotions are riding high, Bickerton said, “I think the United Methodist Church is finding a way with its rhetoric and its narrative to begin a pretty robust conversation about what’s next.”

“I’ve been saying that I believe God has opened the door for us for the next expression of Methodism. The question is: Do we have the courage to walk through the door?”