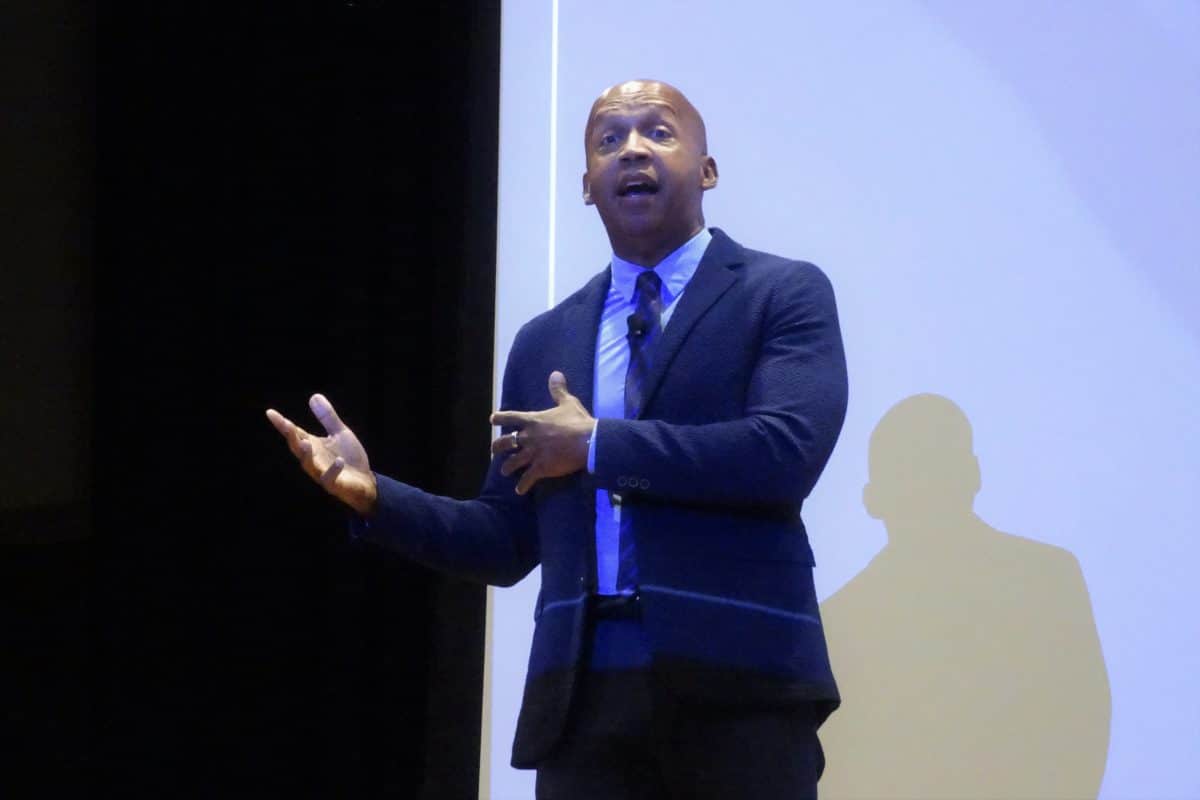

Lawyer and activist Bryan Stevenson challenged Baptists from around the world to be truth-tellers about racial injustices. Speaking to a special session of the Baptist World Alliance’s annual gathering on Thursday (July 14), Stevenson urged Christians to “have this openness and a willingness to admit that we are dealing with a broken history that has to be repaired.”

Although the BWA meeting is occurring in Birmingham, Alabama, this week, Thursday’s session involved a trip to Montgomery to visit two places created by Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative: the Legacy Museum that traces the history of slavery, segregation, lynching, and mass incarnation;, and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice that memorializes the 4,400 victims of terror lynchings from 1877-1950. Stevenson spoke to the group in an EJI facility next to the lynching memorial.

Bryan Stevenson speaks to the annual gathering of the Baptist World Alliance on July 14, 2022, in Montgomery, Alabama. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Stevenson noted that the prophet Micah explained that “God requires of us that we do justice, that we love mercy, and that we walk humbly with him.” And while Stevenson believes that answer “is relevant to what we are struggling with today,” he added, “I don’t know that we’ve actually come to understand what doing justice requires.”

A key to doing justice, Stevenson argued, is truth-telling.

“We’ve got to commit to an era of truth and justice. Because I believe what Micah is talking about when he’s talking about doing justice, he is talking about calling us to truth-telling in service of justice. And what I really want to emphasize is that we are really about a process of truth and reconciliation, truth and restoration, truth and reparation, truth and redemption,” he explained. “You got to do the truth-telling first before you get to restoration and redemption and reconciliation.”

He pointed to what churches teach as an example. People cannot just come in and say they want redemption and salvation and “all of that good stuff, but I don’t want to admit to anything.” Stevenson said the pastors in his church instead “will tell you that first there has to be confession and repentance, and confession and repentance opens up your heart and that’s how redemption and grace and love and salvation comes in. But you cannot skip the first part if you want the second part.”

Part of truth-telling, Stevenson argued, is “we’re going to have to change the narratives that allow injustice to persist.”

“Right now, wherever you are in the world, there are these emerging narratives that are advancing inequality and injustice. And I think it’s actually rooted to what I call the politics of fear and anger,” he explained. “We have so many people in our countries who are distracted by these narratives of fear and anger. We’ve got elected officials and politicians that preach fear and anger. And when you allow yourself to be governed by fear and anger, you start to tolerating things you should never tolerate. You start accepting things you should never accept.”

As examples, he pointed to ethnic abuse in parts of Africa, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and historical genocides like in Rwanda and with the Holocaust. He also pointed to the U.S. where fear and anger prevent more progress in addressing racial injustice.

“If you go anywhere in this country, you go into spaces where the atmosphere has been corrupted by this long history of racial injustice. There are toxins in the air,” he said. “They’ve been created by centuries of inequality and injustice. And some have argued that at some point these toxins will dissipate. But I don’t believe that. I believe we’re going to have to change the narrative.”

“I think we are being called in this moment to talk about things that we haven’t talked about before. I don’t think we can change the narrative until we start acknowledging what this history has done, what fear and anger has done,” he added. “I think we’re going to have to talk about in this country that we live in a post-genocide society. I think what happened to Indigenous people when Europeans came to this continent was a genocide.”

Stevenson also noted that a “narrative of racial differences” then “allowed us to tolerate two-and-a-half centuries of slavery.”

“It was 12 million people abducted from the African continent, put on ships, chained, trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean. Two million died there. The bones of two million people lying at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. And we hadn’t really reckoned with that violence, with that loss, with that tragedy,” he said. “But the real evil of slavery in my judgment, it wasn’t the bondage, it wasn’t the forced labor. The real evil of slavery was the narrative that we created to justify enslavement because there were people who called themselves ‘Christians’ who enslaved other people. There were people who called themselves ‘Baptists’ who enslaved other people. And they didn’t want to feel immoral or unjust, so they had to create a narrative that justified enslavement.”

Thus, even after slavery, the narrative of White Supremacy fueled more violence, like the lynchings that EJI’s national memorial remembers.

“This national memorial is an effort to acknowledge the violence. And we haven’t really talked about all of the destruction done by decades of terrorism,” he said. “And we were silent in the church throughout most of this history.”

Such truth-telling, Stevenson said, can change the narratives. He pointed to the example of Berlin where stones are placed next to where a Jewish family lived or worked, and there’s a Holocaust memorial in the center of the city. Such memorialization changes the narrative.

“There has been this reckoning with that history. And as a result there are no Adolf Hitler statues in Berlin. There are no monuments to the perpetrators of the Holocaust in Germany,” Stevenson said. “But you’re sitting in a city where the landscape is littered with iconography to those who defended its slavery, who romanticized White Supremacy or argued for that kind of hierarchy. And it reflects an absence of truth-telling.”

“I don’t talk about slavery and lynching and segregation because I want to punish America. I don’t talk about inequality and injustice because I want to punish people. I talk about these things because I want liberation. I think there’s something better waiting for us,” he added. “I think people of faith have a critical role to play. We have to be the leaders. We have to show people that you don’t have to fear truth-telling because what comes after truth telling is grace and love and redemption.”