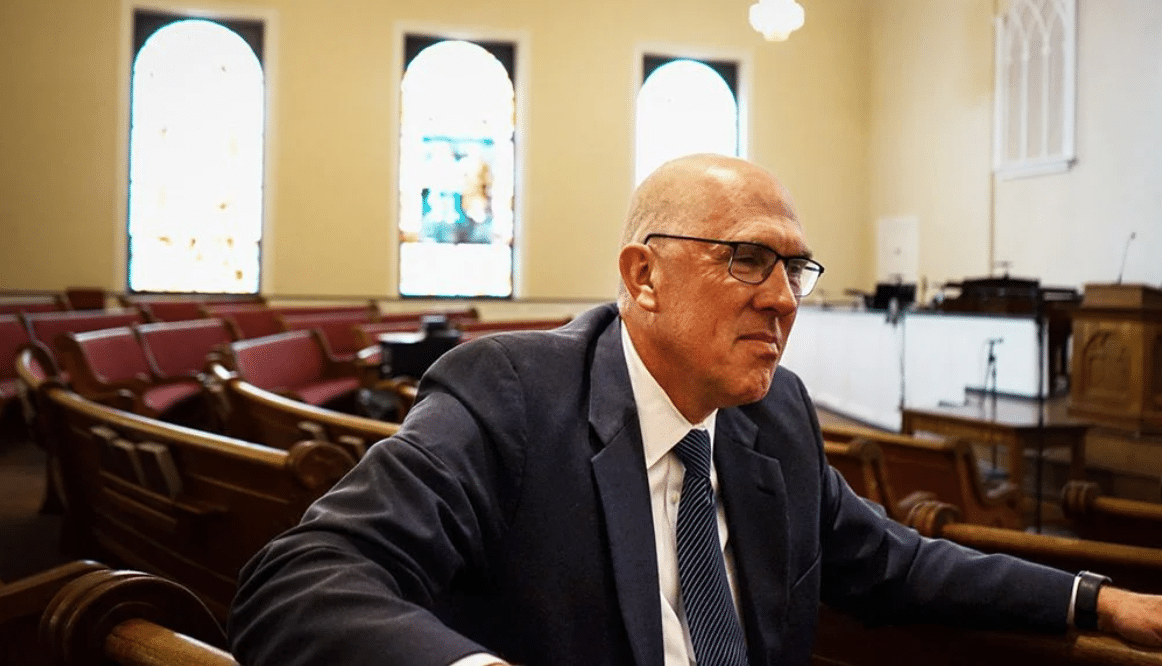

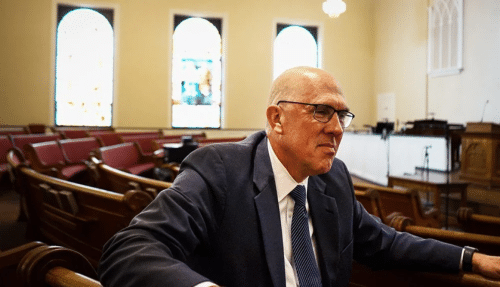

Bart Barber sits in a pew after a service on July 17, 2022, in First Baptist Church of Farmersville in rural northeast Texas, near Dallas. RNS photo by Riley Farrell

FARMERSVILLE, Texas (RNS) — Fighting summer sunlight tinged mauve by stained glass windows, a screen at the front of the sanctuary flashed the week’s birthdays as members of the First Baptist Church of Farmersville filed in for the 11 a.m. service — business as usual at the tiny rural church an hour from Dallas.

Except for one thing: A month before, the church’s pastor, Bart Barber, had been elected president of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Barber succeeds Ed Litton, an Alabama pastor who declined to run for a customary second term as president, adding more drama to the denomination’s 2022 annual meeting, where Southern Baptists approved a series of reforms to address sexual abuse. Those reforms had been drawn up after a report, released days before, found SBC leaders had mistreated survivors of abuse by pastors and church staff for years and sought to downplay its severity.

While he has been involved with SBC polity for years — he was the head of the resolutions committee that selected and shaped many of the proposed reforms — Barber is the first SBC president in nearly two decades not to emerge from an urban or suburban megachurch. During an interview in Farmersville, he said that the jump from leading a small-town church to representing the nation’s largest Protestant denomination is “tons of pressure every day, starting at 4 in the morning.”

At the 11 o’clock service, Barber looked none the worse, delivering a sermon on grace and forgiveness based on a passage from the Book of Leviticus. He excoriated social media cancel culture as the modern equivalent of a bloodthirsty mob, before reviewing Farmersville’s recent Bible youth retreat. Some campers, he jested, “met Jesus for the first time. Others met COVID BA.5.” The hundred or so predominantly white congregants in the pews laughed appreciatively.

Barber’s win at the June meeting in Anaheim, California, represented progress in the SBC’s long battle over sex abuse reform. He supports the appointment of a task force in charge of creating a long-sought database of abusers for use in background checks and urging greater accountability.

But Barber also talks about shifting the balance “to the people” of the SBC, arguing that decentralization — preserving the historical autonomy of the denomination’s churches — will mean more transparency and vigilance in preventing further sexual abuse.

“The SBC is decentralized in terms of polity for the same reasons that the (U.S.) Constitution, if it were being followed, is decentralized in terms of polity,” Barber said. “We are decentralized because of a suspicion of power.”

Critics argue the SBC’s decentralized structure makes it more difficult to discover abuse and hold its perpetrators accountable. SBC leaders long emphasized that churches’ independence meant the SBC had no ability to force specific action against abuse, and insisted SBC leaders could not keep a database because they had insufficient oversight.

The SBC’s adherence to decentralization was an “excuse,” said Grant Gaines, senior pastor of Belle Aire Baptist Church in Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

The SBC’s lack of oversight, but mostly its mismanagement, allowed abusers to slip through the cracks, Gaines said, adding that most SBC leaders and churches now want to collaborate to address the abuse.

But Barber’s vision of the SBC is small-d democratic, and nonhierarchical. He wants to champion the unheard voices of Southern Baptists in the far-flung, often isolated rural churches like his. Barber said he hopes to use social media to give a voice to SBC members who’ve previously been ignored. “Social media democratizes the ability to be heard,” said Barber, who has more than 20,000 followers on Twitter and has tweeted just shy of 50,000 times.

Some of his impetus comes from a proposal originally forwarded by Oklahoma pastor Luke Holmes in 2021 and adopted at this year’s meeting in Anaheim that resolved to “establish, help, and revitalize” churches in towns with fewer than 25,000 people.

The resolution identifies rural areas as places where “Jesus regularly identified himself with … like Nazareth,” painting small churches as mission fields. It also recognizes the difficulty of leading such outposts, calling attention to rural pastors’ vulnerability to anxiety, isolation and depression.

Barber, who has spent 23 years in Farmersville (population 3,500), said that growing smaller churches is a “timeless” idea and hosted a Twitter Space to explain the rural resolution after it passed.

“It was like, ‘How is it that we haven’t done this resolution yet?’” he said.

Barber often posts photos and videos of his ranch and his cattle — one of which is named Bully Graham — but ranching is more than a branding choice. A re-emphasis on rural churches, he believes, can reconnect Southern Baptists with what initially attracted them to the faith, he said.

Nancy Gilmer, who has been missions director at Barber’s church since 2017 and a “Southern Baptist since before I was born,” agreed that focusing on rural churches made strategic sense. The majority of Southern Baptist churches have 100 members or fewer, said Gilmer.

“Small-town fellowship means the church is my family,” Gilmer said. “We’ve raised each other’s kids, we care about each other, we serve together.”

Gilmer added that Barber is what the SBC needs as it tries to heal divisions that have cropped up over the sexual abuse scandals and over race, which conservatives have blamed on “wokeness.” Gilmer calls Barber a “normal guy” whom God is using to secure a future of a united SBC.

“Outsiders looking in can see that we’re having some family squabbles,” Gilmer said. “God has been cleaning house for the last few years and reshaping us for His glory.”

For his part, Barber often talks and tweets about an “army of peacemakers,” referring to a grassroots coalition of Southern Baptists who can find unity in the Bible. Such peacemakers are “the immune system of the church,” he says in his church website’s FAQs.

The army of peacemakers became an unofficial campaign slogan for Barber’s run for presidency, contrasting with #ChangeTheDirection messaging peddled by those in the Conservative Baptist Network, a group of ultraconservatives that has been vocally critical of recent leadership.

“I’m pulling the SBC back from the brink of the sexual abuse scandal, division, factionalism largely created by secular, political forces pushing their way in the church,” Barber told RNS.

“Even if there is a parting of ways or separation in the church, let’s not damage our souls on the way out,” he said.

Identifying the polarity between what he calls the “knuckle-dragging fundamentalists” and “woke or liberal” groups vocal in the SBC, Barber said he does not fit into either camp — and that’s his selling point. (He said he identifies as an “old-time traditionalist” on most doctrinal issues.)

Eddy Daniel, a third-generation Baptist deacon and a member at FBCF for 45 years, said he hopes Barber can succeed in creating common ground to heal the convention.

“Our church is big enough to handle his presidency — not big enough in size, but big enough in its close-knit nature,” said Daniel, referring to Barber as “Brother Bart.”

Barber said his tasks as a peacemaker will not be complete until “Jesus returns.” Still, he said, he will make the decision on whether to run again in due time.

“My decision will be based on answering: Am I still in love with Southern Baptists a year from now? Am I still in love with Jesus a year from now? Is my home church still in love with me?” Barber said. “The presidency of the SBC is not worth losing any of those things.”