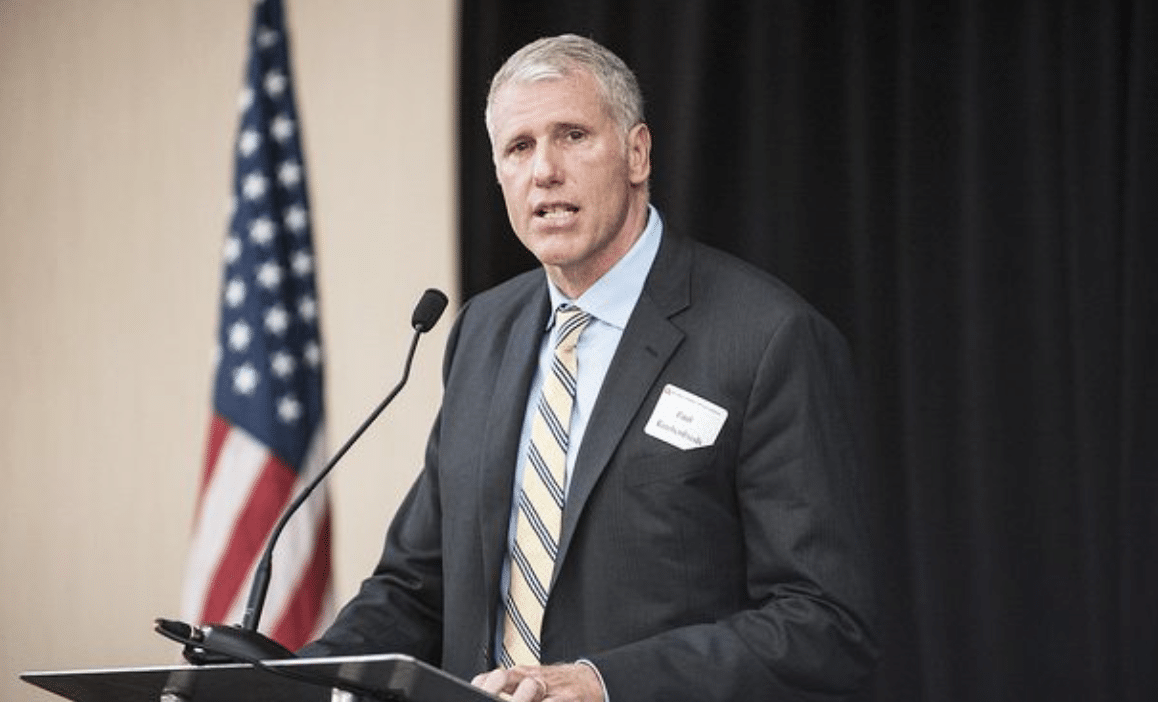

Paul Raushenbush. Courtesy of Raushenbush

(RNS) — The Interfaith Alliance is one of a constellation of nonprofit organizations on the political left, promoting religious pluralism and democracy, that have mobilized as the Christian and political right has dominated the religious liberty debate in recent years.

This week the alliance announced that the Rev. Paul Raushenbush, an interfaith leader, journalist and American Baptist minister, would become its new president and CEO, replacing Rabbi Jack Moline.

A former associate dean of religious life at Princeton University, Raushenbush founded Huffington Post’s religion section in 2009 before serving as senior vice president of Auburn Seminary, and most recently as senior adviser for public affairs and innovation at Interfaith America.

His personal history, as much as his resume, reads like a wall chart of American religious pluralism: He is the great-grandson of Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice, and the great-grandson of Walter Rauschenbusch, the foremost theologian of the social gospel movement in the early 20th century, which sought a Christian rationale for solving social ills such as poverty, alcoholism, crime and child labor. He is currently at work on a biography of his grandmother, the economist Elizabeth Brandeis.

Interfaith Alliance, a small nonprofit with annual revenue of less than $1 million, was formed in 1994 after GOP allies of conservative religious groups scored major gains in the midterm elections, taking back the U.S. House from the Democratic majority after 40 years. It was the beginning of a longterm political shift.

The group established an office in Washington and formed local chapters across the country, challenging the predominance of the religious right by pointing out the ways it was trying to enshrine its beliefs at the expense of America’s religious diversity.

In 2022, that fight has taken on new urgency.

Raushenbush equates his mission to fight Christian nationalism with shoring up democracy, which has been under threat not only from the Jan. 6 insurrection, but in efforts to overturn the 2020 election and waves of voter suppression laws that put minorities at risk.

RNS spoke to Raushenbush, 58, as he was visiting his childhood home in Madison, Wisconsin. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

How does the Interfaith Alliance do its work — advocacy, lobbying?

We do a lot of work on (Capitol) Hill. We talk about legislation to make sure multiple religious voices are heard. We’ve spoken about religious freedom, separation of church and state. We were part of an amicus brief (in support of) the Equality Act. We’re very active on a national level, but there are 20 chapters that work on a local level, which feels as important as ever. I strongly believe that you’ll find religious diversity in every community. It’s important to recognize that’s fundamentally a strength for America, not a threat. This circle has to include everyone. White Christians don’t get to say, ‘This is our country and the rest are lucky to be invited.’

Some religious minorities actually supported the recent Supreme Court ruling allowing a public high school coach to offer a Christian prayer at the 50-yard line. What’s your position?

I think people should be themselves as religious people. But when they start exercising their religion in pluralistic spaces, not recognizing the authority they’re wielding, we’re getting into coercion. We’re getting into the religious freedom rights of the students, not just the coach. I don’t want to erase religion. I’m a pastor and I appreciate the gifts of spirituality. (But) I’m very concerned about the ways religion can be used to coerce in spaces that are supposed to be welcoming to all. Everything has a place. A place for prayer is not a place where some can’t participate. It’s a terrible use of religion.

Is separation of church and state going to be a big issue for the Interfaith Alliance?

Absolutely. The origin of church and state is to protect religion from over-encroachment by the state. Public schools should be places where people can come as they are. That includes nonreligious people, whether secular humanists or atheists. I’m not interested in erasure. I want to draw the line at making religion positive and non-coercive.

How does the Interfaith Alliance gain traction on this issue?

People are recognizing that the Supreme Court’s agenda is informed by a religious perspective that is alienating to the majority of Americans. What we’re seeing is the effort of a minority — white Christians — attempting to exert undue influence on the majority of Americans. People are aware of that. If you look at religious communities, almost everyone views pluralism and multi-faiths as a positive. That’s what we’re going to be putting out there. We’ll be good partners and we’ll invite others to partner with us.

Do you have any particular partners in mind?

I want to work with various religious traditions, but I’m also interested in some unlikely alliances. What do people doing legal work, like Democracy Forward, have to say about this? What does it mean to partner with organizations, like PEN America, that are involved in freedom of speech and freedom of expression?

You’re starting your new job in September. What are your immediate plans?

We’re going to see a lot more mobilization. We will be appropriately involved in the midterm elections and working hard around preservation of democracy and voting rights, viewing that as an important component of freedom of conscience. I want to widen the base. I want people to feel that the Interfaith Alliance can be a great partner, even if you’re not a religious organization.