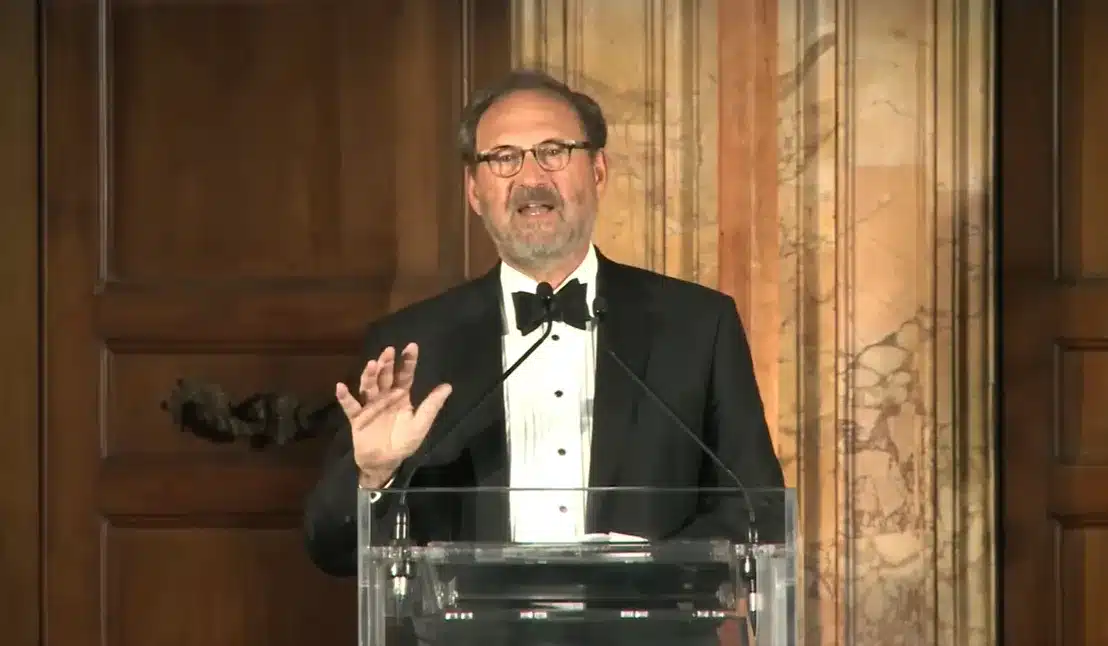

During remarks last month in Rome delivered at a religious liberty event hosted by the University of Notre Dame Law School, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito issued an ominous warning: “There’s growing hostility to religion or at least the traditional religious beliefs that are contrary to the new moral code that is ascendant in some sectors.”

In Alito’s thinking, this animosity has sparked a “battle to protect religious freedom in an increasingly secular society.” He added his concern that our “stable and successful society in which people of diverse faiths live and work together harmoniously and productivity while still retaining their own beliefs” is under threat. Channeling Richard John Neuhaus, the justice cautioned against a privatizing of religious belief and practice where the cultural expectation is that “when you step outside into the public square in the light of day you had better behave yourself like a good secular citizen.”

Given these cultural shifts, Alito argued that “the challenge for those wanting to protect religious liberty in the United States, Europe, and other similar places is to convince people who are not religious that religious liberty is worth special protection, and that will not be easy to do.”

Screengrab as Justice Samuel Alto speaks on July 21, 2022, to the Notre Dame Religious Liberty Summit in Rome, Italy.

While Alito is right to worry about the erosion of religious liberty, his speech misdiagnosed the problem. Although he referenced multiple faith traditions, he revealed his real concern to be opposition to “traditional religious beliefs” by those subscribing to “the new moral code.” This depiction sets up an antagonism between supposedly secular progressive ideas and conservative religious understandings, with the latter needing special protection from the law and the government.

Additionally, he suggested only religious people care about or need religious liberty — as if secular people don’t have such First Amendment rights. And this framing of secularism as the enemy of religious liberty glosses over religious persecution done by religious people. Yet, he argued, “It is hard to convince people that religious liberty is worth defending if they don’t think that religion is a good thing that deserves protection.”

This mindset contradicts the historic understanding and practice of religious liberty in the United States. Ironically, conceptualizing religious liberty in this way actually undermines the protection it offers. Rather than bolstering the rights of all, Alito wants to redefine religious liberty as carving out special exemptions for some.

In this edition of A Public Witness, we interrogate the encroaching secularism Alito fears. Then we cross-examine recent Supreme Court rulings to identify how Alito’s logic is already at work. Finally, we appeal the verdict rendered by some in the media that Alito and other justices are taking the high court in a “pro-religion” direction.

Secularism Isn’t So Scary

Ryan Burge, a Baptist pastor and political scientist, explained in his book examining this group that the nones have become “statistically the same size as the largest religious groups in the United States.” Yet, he cautions against depicting members of the “nones” as hostile to religion. The vast majority of those in the category identify as “nothing in particular,” which reflects a relative indifference towards religion. As Burge wrote, “These are people that just don’t feel strongly about religion one way or the other.”

These statistical trends provide support to the argument made by the philosopher Charles Taylor in his 2007 tome A Secular Age. He unpacked “the shift to secularity” as involving “a move from a society where belief in God is unchallenged and indeed, unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option among others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace.” Alito seems to be wrestling with this new reality, interpreting it to imply an inherent conflict between those subscribing to religious and secular worldviews.

In their study of secularism’s political effects, political scientists David Campbell, Geoffrey Layman, and John Green offered superficial support of this worry. Their book Secular Surge documents how this new religious-secular divide is associated with the widening political polarization. Looking at political party elites, they found religious belief to be more salient to Republican leaders and secularist thinking more common among Democrats. Our political fights increasingly reflect this difference in thinking.

Atheists hold signs outside the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C., on June 27, 2005, to protest efforts to undo church-state separation. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Yet, there is much more to the story. There remains strong diversity within each political party. For example, the Democratic coalition includes both secular-minded voters and many African Americans who are fervently religious. And there is great diversity within the secular category (i.e. atheists are different from agnostics who are different from the nones), which prevents secularists, at least thus far, from forming a strong sense of social identity. Creating the “Secular Left” requires greater ideological coherence and organization than currently exists.

Whatever the reality, there’s another reason to be suspicious of Alito’s fears of a rising secularism hollowing out religious liberty: the Constitution itself. Deriving the government’s authority from the consent of the governed and aware of the (potentially violent) discord that arises from conflicting religious passions, those who drafted the authorizing document of the United States rooted its ideas in a secular foundation that protected rights of religious practice.

“[The Founding Fathers] quite deliberately created a secular government through the establishment clause while enshrining an individual right to religious liberty through the free exercise clause,” Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern wrote for Slate in a piece critical of Alito’s remarks. “To them, secularism was not a menace to religion, but a crucial component of it: History taught them that once the government got involved with matters of faith, it harmed both church and state.”

Unfortunately, recent rulings by the Supreme Court demonstrate that a majority of the justices have forgotten this crucial lesson.

Privileging Religion

With a Republican dominance taking hold of the Supreme Court, a string of recent rulings reinterpreted the religion clauses of the First Amendment. Collectively, these cases effectively diminish the role of the Establishment Clause. Two examples from the court’s last term illuminate this shift.

First, a 6-3 ruling in Carson v. Makin ordered Maine to spend taxpayer money intended for public education on sectarian schools. With some rural parts of Maine lacking the resources to sustain public secondary schools of their own, families could use taxpayer resources for their children to attend alternative schools, public and private. For decades, Maine had barred schools that proselytize from receiving these funds not because of religious animus but to respect church-state separation.

Writing for the Court’s majority (which included Alito), Chief Justice John Roberts reasoned that this practice constituted “discrimination against religion. A state’s antiestablishment interest does not justify enactments that exclude some members of the community from an otherwise generally available public benefit because of their religious exercise.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her dissenting opinion also signed by that Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan that “in just a few years, the Court has upended constitutional doctrine, shifting from a rule that permits states to decline to fund religious organizations to one that requires states in many circumstances to subsidize religious indoctrination with taxpayer dollars.” With the Carson ruling, she added, “The court leads us to a place where separation of church and state becomes a constitutional violation.”

A demonstrator holds a sign on July 18, 2022, in front of the U.S Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. (Mariam Zuhaib/Associated Press)

Six days later, the same 6-3 split ruled in Kennedy v. Bremerton for a football coach leading students in audible, public prayers while on the job on school property. Ignoring the inherently coercive nature of such practices that violate both the Establishment Clause and the free exercise rights of students and players, the justices in the majority prioritized the claims made by a school official who exercised power over students and was paid by public tax dollars. To justify this ruling, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in the majority opinion that Alito signed onto: “The only meaningful justification the government offered for its reprisal rested on a mistaken view that it had a duty to ferret out and suppress religious observances even as it allows comparable secular speech.”

Justices Sotomayor, Breyer, and Kagan again dissented.

“[This] decision is particularly misguided because it elevates the religious rights of a school official, who voluntarily accepted public employment and the limits that public employment entails, over those of his students, who are required to attend school and who this court has long recognized are particularly vulnerable and deserving of protection,” Sotomayor argued in response to the majority’s ruling. “In doing so, the court sets us further down a perilous path in forcing states to entangle themselves with religion, with all of our rights hanging in the balance. As much as the court protests otherwise, today’s decision is no victory for religious liberty.”

These two cases operate according to the logic of Alito’s speech in Rome. A rising secularism is aggressively marginalizing religion. The court must serve as a bulwark against violations of religious liberty. The problem with this tale is that it’s not true.

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Fake News

A narrative emerged in recent media reports around these cases that the Supreme Court is increasingly “pro-religion.” These arguments not only misconstrued the substance of the decisions but served as an accomplice to the court’s majority in misrepresenting religion as synonymous merely with a slice of conservative Christianity.

The Carson ruling led a New York Times writer to declare it came from “a pro-religion court,” adding that “the rise of the religious right has made religious freedom a political priority for Republicans.” But neither statement is true. After all, this suggests the three dissenting justices — Breyer, Kagan, and Sotomayor — are anti-religion for opposing the majority’s opinion. In reality, those justices argued that true religious liberty requires a robust separation of church and state.

Additionally, a quick look at some of the organizations who filed an amicus brief supporting Maine’s position in Carson shows the absurdity of the “pro-religion” logic. Among those urging the ruling that the dissenting justices offered: Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, Catholics for Choice, Central Conference of American Rabbis, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, General Synod of the United Church of Christ, Hindu American Foundation, Methodist Federation for Social Action, National Council of Jewish Women, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, Sikh Coalition, and others. A ruling that rejects the perspectives of those groups cannot in good faith be called “pro-religion” unless religion is defined in such a narrow way that these explicitly religious groups are excluded.

But some still rushed to christen the court’s majority as the guardians of religion. For instance, Nina Totenberg of NPR claimed the Kennedy v. Bremerton ruling proved that “the current court is the most pro-religion of any court in nearly 70 years.”

Such an assertion is even more offensive in this case than in Carson, as multiple briefs came from clergy and faith groups urging the justices not to push official prayers in public schools. One brief included the American Jewish Committee, Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, and General Synod of the United Church of Christ. Another brief came from retired military chaplains who care not only about religion but also the religious liberty rights of everyone. Yet another brief came from clergy — including Baptist, Episcopalian, Jewish, Lutheran, and Methodist ministers — in the community where the case emerged as they backed their public school instead of coercive prayer. And other briefs came from church-state scholars, members of Congress, and other experts who are religious.

To the suggestion that a ruling that went against all of those ministers and religious groups was “pro-religion,” there’s no better response than the classic line from A Princess Bride: “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

The news reports suggesting a “pro-religion” court draw on a recent study showing the court does rule more frequently for religious organizations than in the past. And while the authors of the study, Lee Epstein and Eric A. Posner, use the “pro-religion” language, they also offer important nuance to explain the shift that is overlooked by the media reports citing their research: “In most of these cases, the winning religion was a mainstream Christian organization, whereas in the past pro-religion outcomes more frequently favored minority or marginal religious organizations.”

It’s true that conservative Christians fare well with the current majority. But many such victories come at the expense of other Christians and those of other faiths or no faith. The Supreme Court isn’t increasingly pro-religion but instead increasingly antagonistic toward concerns about religious establishment. That means they aren’t promoting religion or religious liberty; they’re moving us closer toward Christian Nationalism where one faith gains civic privileges not afforded to those with other beliefs.

A person carries a cross on June 25, 2022, outside the Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. (Steve Helber/Associated Press)

Such an approach to church-state issues isn’t pro-religion but actually harms religious believers. As John Leland, an influential Baptist minister during the founding era, argued, “Never promote men who seek after a state-established religion; it is spiritual tyranny — the worst of despotism. It is turnpiking the way to heaven by human law, in order to establish ministerial gates to collect toll. It converts religion into a principle of state policy, and the gospel into merchandise.”

That’s why Amanda Tyler of the Baptist Joint Committee, noted these recent Supreme Court rulings and declared to applause at the general assembly of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship in Dallas, Texas, on June 30: “Christian Nationalism is the single biggest threat to religious freedom as we know it today.” It’s bad enough that six justices on the nation’s highest court don’t understand that reality, but it’s even worse when commentators also cast religious liberty advocates as anti-religion.

Towards the beginning of his speech delivered in Rome, Alito suggested that “religious liberty is under attack in many places because it is dangerous to those who want to hold complete power. It also probably grows out of something dark and deep in the human DNA: a tendency to distrust and dislike people who are not like ourselves.”

The justice’s fears about secularism combined with these two recent rulings by the high court leave us wondering whether Alito has reflected on his own counsel. Rather than affording the consciences of all Americans — religious or secular — the same protections, the court seeks to advantage some perspectives and practices over others. In tearing down the Establishment Clause, the court seems to distrust and dislike Americans who don’t adhere to the majority’s restrictive understanding of what constitutes religion.

Alito and the other justices in the majority believe they are doing religion a favor. In reality, such privilege ends up alienating people who feel (conservative) Christianity is being advantaged in a way that compromises the consciences of others. Alito doesn’t understand that his militant distortion of religious liberty will actually strengthen secularism. That’s a tragedy for both the church and the state.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood