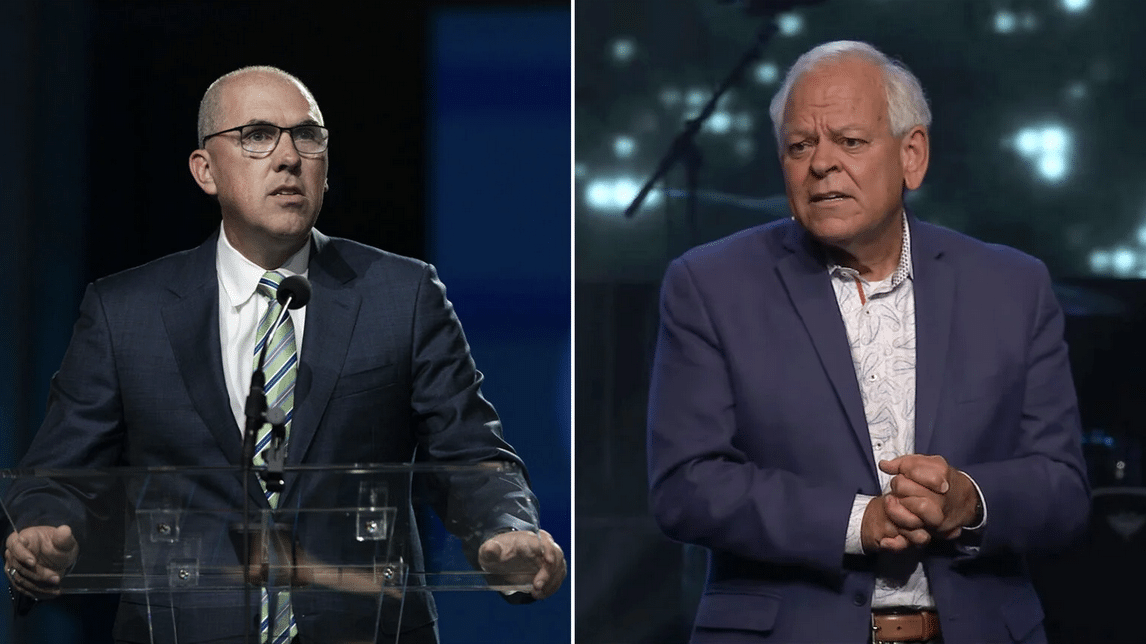

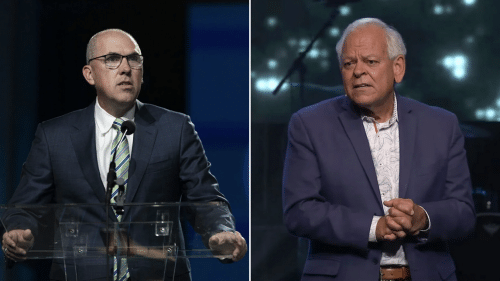

Pastor Bart Barber, left, in 2022. Pastor Johny Hunt, right, in 2020. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, left. Video screen grab, right)

(RNS) — Bart Barber, a country pastor who also happens to be the sitting president of the Southern Baptist Convention, began his Tuesday (Nov. 29) as he does most days, with prayer and feeding his cows.

Before the day was out he would take the rare step of denouncing one of his predecessors.

“I would permanently ‘defrock’ Johnny Hunt if I had the authority to do so,” Barber, who leads a church in Farmersville, Texas, said in a statement released Tuesday.

Hunt, who served as president of the nation’s largest Protestant denomination from 2008 to 2010, stepped aside from public ministry in May after allegations that he had sexually assaulted another pastor’s wife were made public. Then, last week, a group of pastors announced that Hunt has been restored to ministry, less than six months after Southern Baptists passed a series of reforms designed to address a sex abuse crisis.

In addition to his statement, Barber went on social media to call Hunt’s return “a repugnant act.”

Barber was elected at the SBC’s 2022 annual meeting, where the delegates charged him with implementing abuse reforms passed in the same session. But Barber’s defrocking comment points up the challenges he and the SBC face in trying to address abuse.

Because the denomination’s churches are autonomous, no SBC official, including its president, has the authority to discipline Hunt.

But Barber also said the pastors who claim to have restored Hunt do not have that authority either.

“The idea that a council of pastors, assembled with the consent of the abusive pastor, possesses some authority to declare a pastor fit for resumed ministry is a conceit that is altogether absent from Baptist polity and from the witness of the New Testament. Indeed, it is repugnant to all that those sources extol and represent,” he said.

The fact is that the denomination’s institutions have long been run by powerful pastors and their friends, who have used their positions to protect their reputations and the reputation of the convention.

Celebrity pastors like Hunt, because they fill seats and offering plates, often act as what University of North Carolina historian Molly Worthen has called “pastor-warlords,” with little oversight or accountability.

Tiffany Thigpen, an abuse survivor and longtime advocate of abuse victims, said Hunt’s return to ministry is a sign that the legislated reforms have yet to change Southern Baptist culture.

“We are always going to have this network of powerful men who can do whatever they want and think they can get away with it,” she said. “And they are right.”

Thigpen said Hunt, like anyone, can be forgiven by God. But that does not mean he should be given power and a platform in the church. She said pastors like the ones who endorsed Hunt dole out cheap grace in order to protect their friends.

“They don’t care,” she said.

The allegations about Hunt came as a shock to his many admirers. The first Native American president of the SBC, he spent three decades as a popular speaker and pastor of First Baptist Church in Woodstock, Georgia, a prominent megachurch.

In 2010, after his term as president ended, Hunt took an extended leave of absence, citing health reasons. But a 2022 report commissioned by SBC leaders from Guidepost Solutions, an investigative firm, revealed that Hunt had been accused of sexually assaulting another pastor’s wife and had undergone a secret counseling process. The survivor of the alleged attack and her husband were pressured to forgive Hunt, according to Guidepost.

“We include this sexual assault allegation in the report because our investigators found the pastor and his wife to be credible; their report was corroborated in part by a counseling minister and three other credible witnesses; and our investigators did not find Dr. Hunt’s statements related to the sexual assault allegation to be credible,” wrote investigators.

Hunt did not inform his church of the incident in 2010, nor did he tell convention leaders, including leaders at the North American Mission Board, where he became a vice president after leaving First Baptist.

“Johnny Hunt is a serial liar and he lied to every ministry he worked with for years,” said Griffin Gulledge, a Georgia pastor who has been outspoken about the need to address abuse in the SBC. “He told everyone he was morally qualified to be a pastor and he was not.”

Gulledge said Hunt’s recent restoration was not credible, in part because the process was led by friends of Hunt — rather than First Baptist in Woodstock.

“It’s infuriating,” Gulledge said.

Christa Brown, an abuse survivor and another longtime advocate for reform in the SBC, said she appreciated Barber’s comments.

“But so what?” she said. “Nothing has changed.”

Brown said that Hunt’s return, and a lack of action to hold former SBC leaders accountable for mistreatment of abuse survivors, shows “a gross inability to deal with the issue.”

Brown wants printed copies of the Guidepost report available to every church and wants the denomination’s standing body, the Executive Committee, to be as vocal and diligent as she and other survivors have been in educating church members and the public about the threat of abusive pastors.

“Until I see that,” she said, “I won’t believe they are serious.”

Hunt is scheduled to appear in February at a “Great Commission Weekend” hosted by a Florida church. An advertisement for the event, posted on social media by the Rev. Timothy Pigg of Fellowship Church in Immokalee, Florida, features photos of Hunt, along with former SBC Presidents Ronnie Floyd and Jerry Vines and SBC presidential candidate Mike Stone.

Floyd stepped down as president of the SBC’s Executive Committee when his efforts to control the scope and public release of the Guidepost report failed.

Pigg did not respond to a request for comment. Neither did Hunt or Stone.

North Carolina pastor Bruce Frank, who chaired the task force that commissioned and released the Guidepost report, called the video about Hunt’s return “disappointing but not terribly surprising.”

That video, he said, showed no “fruits of repentance” and did not mention the hurt Hunt caused. Frank characterized the process as “just four friends spending a few months with him and now using platitudes saying he’s fit to proceed.”

He also called the decision to give Hunt a platform at a church conference “beyond unwise” and said it sent a terrible message to abuse survivors. Frank said that efforts to address the issue of abuse and to care for survivors will continue, despite challenges.

Particularly disturbing, according to Frank and other critics, was the restoration group’s likening of the situation to the Gospel parable of the good Samaritan, in which a man is beset by robbers, beaten and left by the side of the road. Religious leaders pass him by but a Samaritan rescues him.

“The wounded person on the side of the road is (Hunt’s) abuse survivor, not Johnny Hunt,” said Barber, “and she received no mention at all by this panel — she was passed by, in a way, by this quintet,” he said in his statement. “I do not know her, but I don’t want to be guilty of leaving her on the side of the road. I am praying for her, I have heard her, and I believe her.”

Hunt is the second Baptist leader mentioned in the Guidepost report to make headlines recently. Former Southern Baptist seminary professor and missionary David Sills, who lost his job in 2018 as a professor and as a missionary leader after being accused of abusing a former seminarian, recently sued a number of convention leaders and agencies, including seminary president Albert “Al” Mohler, former SBC President Ed Litton and the SBC’s Executive Committee, alleging they conspired with an abuse survivor to ruin his reputation.

Barber said on social media that he expected his prayer meeting on Tuesday evening to be interrupted so that he could be served with the lawsuit.