As churches across the country gathered for worship Sunday (Jan. 15) on what would have been Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 94th birthday, two significant Baptist congregations welcomed to the stage national politicians eyeing 2024 presidential runs. But the two men — like the two churches — offered quite different visions of faith and politics today.

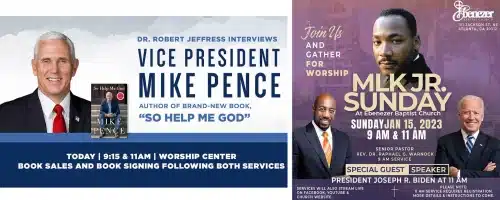

Former Vice President Mike Pence showed up at First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, to promote his new book So Help Me God. Like the book, his appearance at the important MAGAchurch was a way of testing the waters to see if Republican voters are ready to shift from chanting “Hang Mike Pence” to voting for him. He appeared on stage with pastor and Foxvangelist Robert Jeffress, who has been one of former President Donald Trump’s biggest religious cheerleaders.

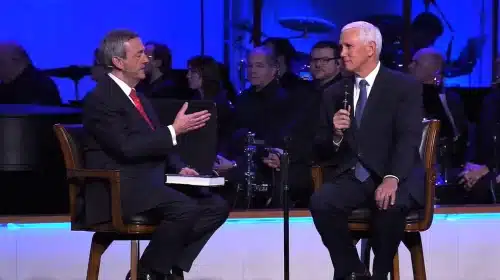

About 10 minutes after Pence finished speaking during the first service in Dallas, President Joe Biden walked onto the stage at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia. The church where King served alongside his father at the time of the civil rights leader’s assassination remains an important site for the social witness of Black Christians. But he wasn’t the only politician standing in front of the congregation. The current pastor, Rev. Raphael Warnock, is also a Democratic U.S. Senator. The nation’s oldest president became the first sitting president to preach at that church during a Sunday service. And he did so while pondering whether to seek four more years.

Although this is a tale of contrasts, it’s not so on a Dickensian level. The famous Charles Dickens line — “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times” — is much too dramatic. Neither of these political pulpit moments were close to the best nor the worst. But they do offer insights into competing visions among Christians about what the nation and its churches should look like.

So this issue of A Public Witness takes you to church — twice — to listen to the evangelistic appeals of Mike Pence and Joe Biden. Then the two messages are considered together to offer insights into the religious divide in American politics.

The Book of Mike

The last time Mike Pence showed up at First Baptist in Dallas, he was officially a candidate. As the Trump-Pence ticket sought reelection in 2020, Pence campaigned from the pulpit in the middle of a pandemic (and amid an outbreak in the unmasked choir behind him). That was definitely a preaching-to-the-choir moment as the church’s choir had earlier made headlines for singing a new hymn titled “Make America Great Again.” And the church’s pastor, Rev. Robert Jeffress, was an early supporter of Trump during the 2016 race because, as he explained, “I don’t want some meek and mild leader or somebody who’s going to turn the other cheek. I’ve said I want the meanest, toughest SOB I can find to protect this nation. And so that’s why Trump’s tone doesn’t bother me.”

But a lot has changed since 2020. Mainly, an insurrection. When a pro-Trump mob, many of them carrying Christian flags or other Christian symbols, attacked the U.S. Capitol, some constructed gallows for Pence (with people in the crowd writing “In God We Trust” and “God Bless the USA” on the gallows). Those feelings haven’t gone away among true believers. Social media reactions to the announcement that Pence would speak showed some conservatives critical of the church for inviting a “traitor” or “Judas” to the sanctuary.

Jeffress asked Pence how his faith impacted his actions on that fateful day. But before talking about Jan. 6, Pence stressed that he “shared the concern of millions of Americans about voting irregularities that had taken place.” After giving more oxygen to debunked claims about the 2020 election results, Pence correctly insisted the Constitution did not allow him to singlehandedly reject the votes sent to Congress.

“What grounded me there in that was that verse in Psalm 15. It says, ‘He keeps his oath even when it hurts.’ And I know something about that,” Pence said.

“We have often told our children, ‘The safest place in the world is to be in the center of God’s will.’ We knew we were where we were supposed to be, doing what we were supposed to be doing, whatever the consequences of that. And the Lord sustained us through that time,” he added. “I truly do believe that the Lord led us on a path in our lifetime to come to that moment, and I give him all the glory for whatever we were able to do, alongside others, on that day.”

Screengrab as Rev. Robert Jeffress (left) interviews Mike Pence during the first service at First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, on Jan. 15, 2023.

Pence also defended what the Trump-Pence administration had accomplished prior to Jan. 6 (though he never mentioned Trump’s name in the first service and only did once in the second). He admitted “the administration did not end well and ended in controversy,” but he insisted it “doesn’t ever diminish” his gratitude to have been part of it.

“I’m incredibly proud of the record of our administration,” he said. “And I couldn’t be more grateful to have been a vice president in the administration that appointed three justices that gave America a new beginning for the right to life in the last year.”

Pence also worked in subtle jabs at the new administration, arguing we need to “have government as good as our people again.” He also complained about “the suppression of speech, the infringements on religious liberty.”

Beyond Jan. 6, Pence talked about his time in office in spiritual terms. Jeffress also stressed this in his leading questions as he decried the principle of church-state separation and complained about being labeled a “Christian Nationalist.”

“Every time I took the oath of office, it ended with a prayer: ‘So help me God,’” Pence explained. “I hope, as the title suggests, that they also find in the pages of that book my deep conviction that everything that I’ve done, everything we’ve been able to do in our lives, and the strength of our family, our service, it’s all because of God’s faithfulness. And so I tell people the title of the book is So Help Me God and the last three words are ‘thank you, Jesus.’”

“Having men and women of faith in public life who lean on the wisdom of the scriptures and on prayer for decisions that they make strengthens the life of the nation. And so it shall ever be,” Pence said. “I hear the term ‘Christian Nationalists.’ It seems to me to be something of a pejorative these days among the leftwing media. But the truth of the matter is this nation has ever been sustained by Christian patriots who believe in America. And so it shall ever be. America is a nation of faith.”

Although Pence hit the expected notes for a conservative evangelical congregation, the applause during and after his remarks was much more subdued than when Trump spoke in that sanctuary just 11 months after the insurrection. Jeffress praised Pence for his “courage” on Jan. 6 as he “protected our Constitution,” but even that garnered only a polite response. The congregation might like Pence, but they love Trump.

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

The Gospel of Democracy

As the choir at Ebenezer Baptist in Atlanta opened the service, Joe Biden tried to fit in. But the White Catholic from the northeast struggled to clap on the same beat as the southern Black Baptist congregation. Eventually, he stopped trying and just enjoyed the music. Raphael Warnock, the pastor and senator who introduced Biden, joked about Biden trying to clap even though the service “might be a bit rambunctious and animated” for the “devout Catholic.”

But once Biden stepped to the pulpit, he was in tune with the congregation. Unlike Pence’s reception in Dallas, the faithful gathered in Atlanta frequently erupted to support the president as he honored King and preached the need to protect democracy. While Pence didn’t mention King, Biden frequently praised the famed Baptist preacher as a giant of the faith like Moses, Joseph the dreamer, and John the baptizer.

“Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was a nonviolent warrior for justice who followed the word and the way of his Lord and his Savior,” Biden said. “We gather to contemplate his moral vision and to commit ourselves to his path. The path that leads to the beloved community, to the sacred place and that sacred hour when justice rains down like waters and righteousness was a mighty stream.”

After honoring King, Biden argued the U.S. is “at what we call an ‘inflection point,’ one of those points in world history where what happens in the last few years and will happen in the next six or eight years, they’re going to determine what the world looks like the next 30 to 40 years.”

President Joe Biden claps at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, on Jan. 15, 2023, during a service honoring Martin Luther King Jr. (Carolyn Kaster/Associated Press)

“This is the time of choosing,” he added. “Are we a people who will choose democracy over autocracy? … We have to choose a community over chaos. Are we the people who are going to choose love over hate?”

These choices, Biden insisted, are related to what King worked for in the civil rights movement — and such a struggle for democracy should be seen in spiritual terms.

“We do well to remember that his mission was something even deeper. It was spiritual. It was moral,” Biden said. “The goal of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which Dr. King led, stated it clearly and boldly, and it must be repeated again, now: to redeem the soul of America.”

The latter phrase, which Biden used for his 2020 presidential campaign, is key to how Biden views the intersection of faith and politics.

“The soul of America is embodied in the sacred proposition that we’re all created equal in the image of God,” he explained. “That was the sacred proposition for which Dr. King gave his life. It was a sacred proposition rooted in scripture and enshrined in the Declaration of Independence.”

Biden called “the battle for the soul of this nation” a “constant struggle,” including “against those who traffic in racism, extremism, and insurrection.” Instead of heeding those voices, he added, “at our best, we hear and heed the injunctions of the Lord and the whispers of the angels.”

One sign of progress for democracy he highlighted was the move in one generation from segregation to Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson on the U.S. Supreme Court — a declaration that drew a standing ovation. Biden linked that court confirmation to King’s dream: “As Dr. King said, ‘Give us the ballot, and we will place judges on the bench … who will do justly.’ And we are. That’s the promise of America — where change is hard, but necessary.”

Thus, the president called on the congregation of church members and elected officials to keep fighting for democracy: “We know there’s a lot of work that has to continue on economic justice, civil rights, voting rights, on protecting our democracy, and on remembering that our job is to redeem the soul of America.”

As Biden closed, he quoted a few lines from “I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired.” A few moments later, as he walked away from the pulpit amid another standing ovation, the Ebenezer choir started singing the song.

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

Competing Visions

During last year’s midterms, we covered several inappropriate moments of politicians campaigning during church services. Neither appearance on Sunday rises (or rather sinks) to that level. Neither Pence nor Biden are officially running, which would help shield houses of worship from the prohibition against partisan politicking. And both largely avoided partisan rhetoric, offering only subtle criticisms of the other party.

Other issues important to note include timing and purpose. Pence didn’t preach, which would make his appearance less problematic. But it was basically just a pre-sermon advertisement for his book, so that feels odd for reasons unrelated to politics. And while Biden did deliver the message, it was a special service to remember Martin Luther King Jr. on his birthday. As a public official, Biden’s presence and participation helped honor the slain civil rights leader and his family and friends in attendance on Sunday. Biden also largely centered his remarks on King, weaving in as many biblical references as policy issues. While not quite deep in its exegetical treatment of scriptural texts, it nonetheless fit the occasion of honoring King.

In their remarks, both Pence and Biden argued for upholding democracy and the Constitution, with both seeing the violence on Jan. 6 as a threat. But they diverged significantly in how we got there and what happens next. Pence continued to peddle claims of election “fraud,” and he suggested the reforms needed today are for “voter integrity.” Biden, on the other hand, called for the congregation to seek “truth” and work to protect “voting rights.” For Pence, democracy was saved by a man of God (himself) following his oath. For Biden, that was too close for comfort, thus people of faith must continue to fight for democracy and the “soul of the nation.”

Interestingly, one of the few specific examples of administrative success mentioned by either Pence or Biden was the appointment of Supreme Court justices — and both of them referenced this. But the justices named by Pence are rarely in agreement on critical cases with the one Biden mentioned. These are two different visions of justice, each wrapped up in religious values. The politicization of the highest court in the land clearly resonates not just on cable news but also in the pews. After all, for both men the reference to confirming a justice or justices was a top applause moment.

Both Biden and Pence also stressed the importance of faith in public life and among those in public office. While Pence’s rhetoric — both on Sunday and before — more explicitly pushes Christian Nationalistic themes, Biden offers a softer version that sacralizes American ideas and founding documents. But the differences here likely create more significant consequences in tone and policy than the similarities.

With these two “preachers” and at these two churches we find vastly different religious-political visions for the nation. We also have another vision as Trump preaches a political gospel different from both Biden and Pence. We’ll continue to see these competing visions playing out over the next two years in campaign rallies, TV ads, and even church services. This means churches across the theological and political spectrums must avoid the temptation of being used as part of the partisan games of politicians.

We must not confuse the city of Washington with the heavenly city. As Charles Dickens put it in A Tale of Two Cities, there is a city the prophets tell us about (that isn’t the one of the politicians): “I see a beautiful city and a brilliant people rising from this abyss, and, in their struggles to be truly free, in their triumphs and defeats, through long years to come, I see the evil of this time and of the previous time of which this is the natural birth, gradually making expiation for itself and wearing out.” Now that will preach!

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor