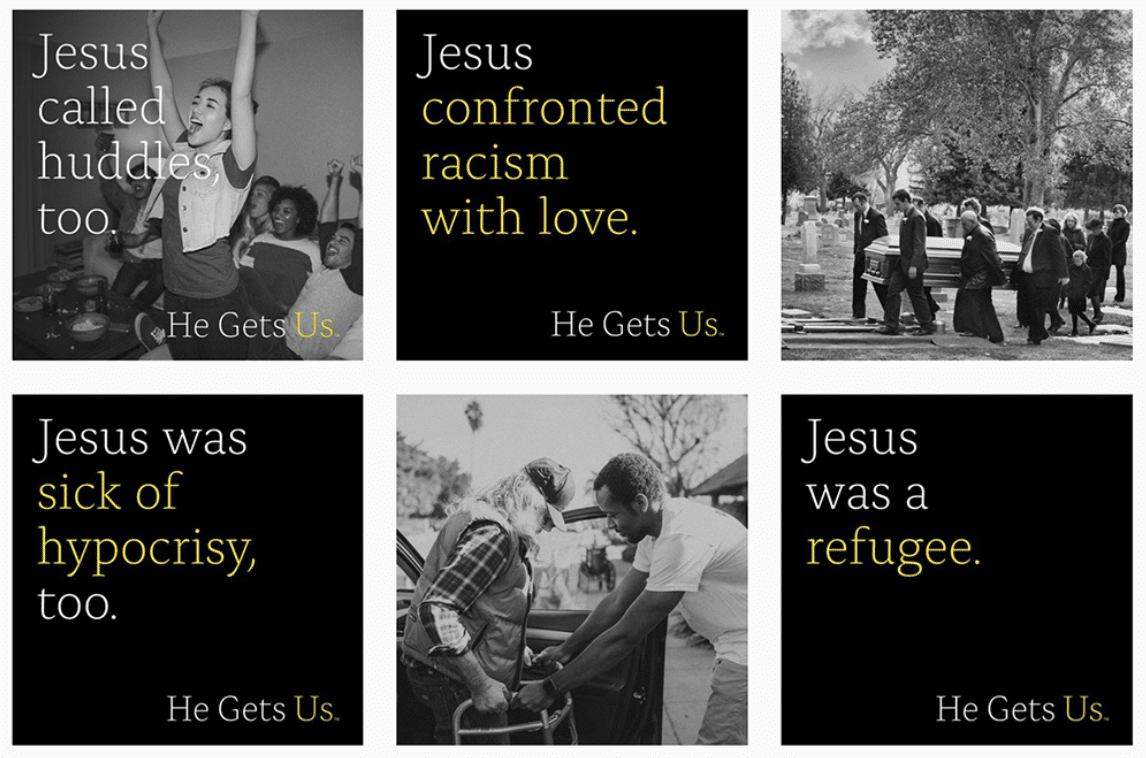

He Gets Us social media posts. Courtesy images

(RNS) — The first time she saw an ad for “He Gets Us,” a national campaign devoted to redeeming the brand of Christianity’s savior, Jennifer Quattlebaum had one thought on her mind.

Show me the money.

A self-described “love more” Christian and ordinary mom who works in marketing, Quattlebaum loved the message of the ad, which promoted the idea that Jesus understands contemporary issues from a grassroots perspective. But she wondered who was paying for the ads and what their agenda was.

“I mean, Jesus gets us,” she said. “But what group is behind them?”

For the past 10 months, the “He Gets Us” ads have shown up on billboards, YouTube channels and television screens — most recently during NFL playoff games — across the country, all spreading the message that Jesus understands the human condition.

The campaign is a project of the Servant Foundation, an Overland Park, Kansas, nonprofit that does business as The Signatry, but the donors backing the campaign have until recently remained anonymous — in early 2022, organizers only told Religion News Service that funding came from “like-minded families who desire to see the Jesus of the Bible represented in today’s culture with the same relevance and impact He had 2000 years ago.”

But in November, David Green, the billionaire co-founder of Hobby Lobby, told talk show host Glenn Beck that his family was helping fund the ads. Green, who was on the program to discuss his new book on leadership, told Beck that his family and other families would be helping fund an effort to spread the word about Jesus.

“You’re going to see it at the Super Bowl — ‘He gets Us,’” said Green. “We are wanting to say — we being a lot of people — that he gets us. He understands us. He loves who we hate. I think we have to let the public know and create a movement.”

Jason Vanderground, president of Haven, a branding firm based in Grand Haven, Michigan, that is working on the “He Gets Us” campaign, confirmed that the Greens are one of the major funders, among a variety of donors and families who have gotten behind it.

Donors to the project are all Christians but come from a range of denominational backgrounds, said Vanderground.

Organizers have also signed up 20,000 churches to provide volunteers to follow up with anyone who sees the ads and asks for more information. Those churches are not, however, he said, funding the campaign.

The Super Bowl ads alone will cost about $20 million, according to organizers, who originally described “He Gets Us” as a $100 million effort.

“The goal is to invest about a billion dollars over the next three years,” he said. “And that is just the first phase.”

One of the ads that aired during the NFL playoffs was titled “That Day” and tells the story of an innocent man being executed.

“Jesus rejected resentment on the cross,” the ad says. “He gets us. All of us.”

A billion-dollar, three-year campaign would be on a par with advertising budgets for major brands such as Kroger grocery stores, said Lora Harding, associate professor of marketing at Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee.

“This is a really remarkable ad spend for a religious organization or just a nonprofit in general,” said Harding, who worked on the “Open hearts, open minds, open doors” campaign for the United Methodist Church.

Religious-themed ads have been relatively rare at the Super Bowl. The Church of Scientology has run ads in the past, and in 2018 Toyota ran an ad with the message “We’re all one team,” featuring a rabbi, a priest, an imam and a saffron-robed monk headed to a football game, where they sat next to some nuns.

Closer to the “He Gets Us” model was the Christian Broadcasting Network’s $5 million national campaign to promote “The Book,” a repackaged version of The Living Bible translation, with a catchy theme song sung by country legend Glen Campbell.

Harding said that despite the cost, advertising at the Super Bowl makes sense for “He Gets Us.” Organizers want to reach a mass audience that is paying attention. Super Bowl ads have become part of the pageantry of the big game.

“There just aren’t ways to reach an attentive, engaged audience that size anymore,” she said.

She also said that the anonymity of the group behind the ads plays to the group’s advantage. It would be easy for viewers to dismiss an ad coming from a faith-based organization or religious group. The “He Gets Us” ads wait until the end to mention Jesus and don’t point to any specific church or denomination.

“That makes it even more powerful, and hits the message home in a really compelling way,” she said. “I think it does make Jesus more relevant to today’s audiences.”

Some viewers, including some evangelical Christians, are skeptical. Author and activist Jennifer Greenberg supports the idea of trying to reach those outside the faith and wants people to understand that Jesus gets them. But that’s not the whole message of Christianity.

“Yes, Jesus can relate to you,” she said. “But what did Jesus come primarily to do? He came to die for our sins.”

Connecting emotionally with Jesus is great, she added. But that won’t save your soul.

“I can look at Buddha or Sarah McLachlan or Obama and I can find things in common with them,” she said. “But that does not mean they are going to save me.”

Michael Cooper, an author and missiologist, agrees. While Cooper is a fan of the ads, saying they powerfully communicate the human side of Jesus, they leave out his divinity.

“I began to wonder, is this the Jesus I know?” he said.

Cooper and a colleague offer what he called a “constructive critique” of the campaign in an upcoming article for the Journal of the Evangelical Missiological Society. That article calls for clearer messaging about the divine nature of Jesus.

“This wasn’t just a great teacher or preacher who was incarnated,” he said. “This was God himself.”

Ryan Beaty, a former Assemblies of God pastor and current doctoral student at the University of Oklahoma, said he’s been fascinated by the ads and wonders how the country’s political polarization may affect how the ads come across.

His conservative friends, he said, see the ads — such as one depicting Jesus as a refugee — as too political. Other folks who are more liberal see the ads as not going far enough.

Beaty also wonders if people outside the church will find the ads more compelling than true believers.

“People of no faith — or moderate learnings toward faith — will find these more compelling than people who identify with the Christian faith or strongly identify with politics,” he said.

Seth Andrews, a podcaster, author and secular activist based in Tulsa, Oklahoma, said the campaign seems to be marketing a version of Jesus that’s more in touch with modern American culture than earlier, more dogmatic versions.

“They are latching on to this touchy-feely, conveniently vague, designer Jesus,” he said.

Andrews poses the question of what Jesus would think of the amount of money spent on the ads. Would he prefer that the money be spent on ministering to people’s physical needs or making the world a better place?

“Or would he say, no, go ahead and spend $100 million to tell everybody how great I am?”

While the ads are meant to reach what Vanderground called “spiritually open skeptics,” a secondary audience is Christians, whose reputations have fallen on hard times in recent years.

“We also have this objective of encouraging Christians to follow the example of Jesus in the way that they love and treat each other,” he said.

For her part, Quattlebaum said that in the end, she’s a fan of the ads, because they focus on the main message of Christianity.

“It all goes to Jesus,” she said. “ And if it all goes back to Jesus, it all goes back to love.”