Once labeled “the runty stepchild among American holidays,” we suspect many people are unaware that tomorrow (June 14) is Flag Day.

Originally proposed in the 19th century to foster both patriotism and an increase in sales of Old Glory by textile manufacturers, President Woodrow Wilson formally established the holiday in 1916 and then Congress enacted the observance into law in 1949. Other than noticing a few more flags flying in your neighborhood, there’s not much more that happens on this occasion meant to commemorate the official adoption of the Star Spangled Banner.

Yet, for Stephen Flick of the Christian Heritage Fellowship, the day is imbued with sacred significance.

“In contemporary Christian America, Christians must look beyond superficial popular presentations recounting national holidays and history to discern the influence Christianity has had upon the conception and construction of America,” he wrote.

So Flick utilizes a common strategy among those propagating the idea that the U.S. is a “Christian” nation. He talks about the faith of Betsy Ross, who is traditionally credited with sewing the first American flag. He points out that Francis Scott Key, originator of the National Anthem, was a devout Christian. Finally, he notes that the author of the Pledge of Allegiance was a Baptist minister (though Flick didn’t mention that the socialist pastor didn’t include “under God” in the pledge).

Somehow the religious background of these various figures makes the flag into a sacred symbol and transforms Flag Day into “A Christian Contribution to America.”

“The more Americans realize how the irreligious and secularists have denied all Americans a right to the appreciation of their Christian heritage, the more deeply they should be resolved not to allow succeeding generations to be robbed of this important treasure,” Flick concluded.

What Flick doesn’t seem to realize is that a lot of Christian pastors are part of this conspiracy as well. Clergy are increasingly pushing back against Christian Nationalism — an ideology that seeks to merge American and Christian identities to defend and uphold a particular social order — espoused by Flick and others.

Flag Day has become the latest focal point of that effort. Led by Faithful America, a coalition of religious groups called on pastors to preach against Christian Nationalism on June 11, the Sunday before the patriotic holiday.

“Faithful America chose the weekend before Flag Day for our ‘Preach and Pray to Confront Christian Nationalism’ event because all too often the flag is made into an idol, sitting near the altar at the front of sanctuaries across the country,” Rev. Nathan Empsall, executive director of Faithful America, told us. “Certainly, as patriotic Americans, we can and do honor our nation’s flag, and as Christians, we venerate Christ before the cross — but while both objects are of great importance to us, only one is godly and only one is part of our faith.”

In this issue of A Public Witness, we listen to some of the sermons preached on Sunday to hear what words from the Lord the participating pastors had to share about the dangers of Christian Nationalism. Then we look more broadly at other ways Christian leaders and denominations are speaking out against this problematic conflation of God with country.

Raising a Banner

Ahead of Sunday, more than 300 clergy and worship leaders from multiple denominations in 45 states signed up to participate in the inaugural “Preach and Pray to Confront Christian Nationalism” weekend. At many churches, this meant addressing the ideology during the sermon, while at others the criticism of Christian Nationalism came as a special reflection during the service. We didn’t watch all the services, but we did attend enough of them virtually to get our perfect church attendance badges for months (if only the attendance points rolled over to other weeks). We’ll highlight a few as examples of how preachers rose to the challenge.

Rev. Rick Oberle argued in his sermon at Columbia United Church of Christ in Columbia, Missouri, that “there are extremists in every religion that have created understandings of God that are not accurate.” For Christians, he pointed to Christian Nationalism as an example (and Pat Robertson, who died last week, as another).

“Christian Nationalism is an invasive movement in our country that is a threat to both democracy and Christianity. Christian Nationalism is a doctrine that combines extremist ideology with a perversion of the Christian faith,” Oberle said. “Christian Nationalism is antisemitic, Islamophobic, homophobic, and consumed with a lust for power. It provides cover for White Supremacy and racial subjugation, and falsely teaches that there should be no divide between church and state.”

Insisting that “Christian Nationalism is not Christian and it is not patriotic,” he also lamented that the ideology helped inspire the Capitol insurrection “in the name of a depiction of God that is extremely flawed.” Christians, he insisted, are instead called to proclaim “God’s loving, grace-filled, all-inclusive, expansive nature.”

Rev. Priscilla Paris-Austin also mentioned Pat Robertson’s passing in her sermon at Immanuel Lutheran Church in Seattle, Washington, as she condemned the “highly problematic” ideology of Christian Nationalism. She argued that like Robertson’s declarations, Christian Nationalism “limits our understanding of who God is, how God functions, and what we can expect to encounter in the great beyond.”

“Pat Robertson had a lot to do with the current political climate that proclaimed, ‘God loves America,’ and somehow in their minds, only America,” Paris-Austin said. “It opens us up to an arrogance that is sinful. When we allow ourselves to believe that somehow God’s love is only for [us], we are removing part of God’s creation from God’s love.”

“How could a God who created the universe limit their love to one geographic country?” she added as she threw up her hands in bewilderment. “It ain’t possible! It’s not God. It is a closed and limited view. … ‘God is bigger’ can be our response to Christian Nationalism. God is bigger than all that.”

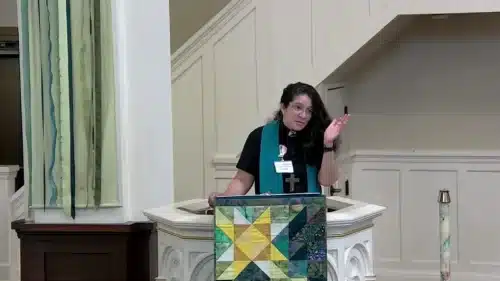

Screengrab as Rev. Priscilla Paris-Austin preaches at Immanuel Lutheran Church in Seattle, Washington, on June 11, 2023.

At First Congregational United Church of Christ in Haworth, New Jersey, Rev. Jack Cuffari similarly emphasized the biblical teachings on love as an inherent counter to the ideology of Christian Nationalism. Insisting the ideology is “the exact opposite of the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth,” Cuffari admitted that because of Christian Nationalism, he knows people sometimes “cringe” when he tells them he’s a Christian. So he criticized Christian Nationalism as “not God-based” but “a twisted, phony scriptural construct.”

“Unfortunately for them — and fortunately for us — the scriptures do not support the idea of Christian Nationalism in any way. Any person who places their devotion to Christ on the same level as their allegiance to their country is guilty of idolatry. Period,” Cuffari said. “Make no mistake about it: When we claim one nation or one people or one group as superior or inferior to another, we’re committing an overt and dangerous sin.”

Rev. Paul Mitchell at Pioneer United Methodist Church in Walla Walla, Washington, also warned about the arrogance of Christian Nationalism and the damage it inflicts on the church.

“Today, in our time and place, there is an insurgence of hubris feeding the phenomenon known as Christian Nationalism,” he declared. “Despite the clear intents of the Constitution to separate church and state and to honor religious liberty to all, Christian Nationalism merges our religious and civic identities, proclaiming that only conservative Christians are true Americans.”

Mitchell warned congregants about the “theocratic policy agenda” and “oppressive legislation” from those pushing Christian Nationalism. That, he added, hurts the Christian witness.

“Christian Nationalism doesn’t just attack democracy and equal rights, it also drives people away from the church,” he said. “We must side with vulnerable communities. And we must reclaim our own identity and prophetic voice.”

Screengrab as Rev. Paul Mitchell preaches at Pioneer United Methodist Church in Walla Walla, Washington, on June 11, 2023.

Among the various problems that emerge from the ways Christian Nationalism distorts Christianity, numerous preachers specifically noted racism. Which is why many scholars and clergy talk about the ideology as White Christian Nationalism. At Middle Collegiate Church in New York City, Rev. Jacqui Lewis connected Christian Nationalism to White Supremacy. She condemned efforts to maintain the Christianity seen in the 1950s because “the Klan and White Protestantism sort of got married together.”

“The church has decided that what is to be centered is male, White, hegemonic, Christian power — in other words, White Nationalism. White Nationalism has become the public face of Christianity,” she said. “White Nationalistic Christianity claiming the megaphone for what it means to be holy, what it means to be good, what it means to be just, what it means to be Christian.”

Lewis also connected such White Christian Nationalism to issues like laws today targeting LGBTQ people, efforts to demonize immigrants at the border, and the election of Donald Trump. Thus, she warned of the efforts of “so-called Christians who actually are White Nationalists” seeking power through any means.

Like Lewis, Rev. Stephen Weissman at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Asheville, North Carolina, pointed to historical examples of Christianity merging with power structures and engaging in unjust and ungodly wars, acts of persecution, and oppression of minorities. He even acknowledged to the church that “our own Anglican history is stained” by such mingling of church and state, which he noted even showed up during the recent coronation service of King Charles III. But he noted that efforts today to better live into ideals of a pluralistic nation that separates church and state have sparked a backlash from those desiring Christian Nationalism.

“Christian Nationalism is a devil’s game to trick Christians into uncritically supporting a system which is imperfect at best and unjust at worst,” he said. “If the church loses its independence to the state, the church will lose its freedom. The church will be more vulnerable to state dominance — dominance which we see in the Patriarch of Moscow blessing Putin’s war upon Ukraine.”

Echoing concerns of several pastors who declared Christian Nationalism to be a misrepresentation of the teachings of Jesus, Rev. Carmen Mason-Browne warned the congregants at Noe Valley Ministry Presbyterian Church in Alameda, California, that they cannot remain “wishy-washy” as others are “trying to hijack our faith, trying to hijack my Jesus.” She argued that “those of us who try to follow Jesus, who try to study this rabbi, who try to get in the word” must speak out.

“The other side is broadcasting a Jesus that is unrecognizable, a faith that is blasphemy, a faith that is heresy,” she said. “And what are we saying? Where are we?”

With her sermon, Mason-Browne joined other pastors in the initiative in raising her voice against Christian Nationalism. Like some, she even mentioned Faithful America and the preaching initiative in her sermon to let the congregation know they were part of a larger movement across the country to push back as “our faith and our beliefs are under attack.” Thus, she added, “we cannot remain silent.”

To that, we join the congregation and say to her and the other preachers, “amen.”

Screengrab as Rev. Carmen Mason Browne preaches at Noe Valley Ministry Presbyterian Church in Alameda, California, on June 11, 2023.

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

A Growing Chorus

These clergy are not voices crying out in the wilderness. The chorus of Christians speaking out against Christian Nationalism is growing. In addition to individual leaders critiquing the ideology, institutional voices are also expressing their concerns.

Earlier this year, Matthew Harrison, president of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, issued a letter condemning extreme views and hateful rhetoric around race, gender, and other topics that had emerged within the denomination. Some of those espousing the views in the denomination identify as Christian Nationalists. So Harrison demanded repentance from the reprobates and consequences if such contrition was not offered.

“This is evil. We condemn it in the name of Christ,” his epistle stated. “Where that call to repentance is not heeded, there must be excommunication.”

This summer, the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) will consider a resolution at its general assembly on this topic. The proposed resolution, “Calling the Church to Oppose Christian Nationalism,” makes a theological case that “Christian Nationalism in practice denies the imago Dei in every human being” and it “misrepresents our faith to our neighbors, thereby, turning people away from the life-giving love of God.”

Thus, the resolution declares that “the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) denounces Christian Nationalism in all its forms as a distortion of the Christian faith, and commits to opposing it wherever it appears, for the sake of the gospel and the good of the human family.”

In September, a high-level group of Latino Christian leaders will gather in Atlanta, Georgia, to discuss how Christian Nationalist ideas arise in Latino evangelical and Pentecostal churches. The convening will explicitly cross theological boundary lines to facilitate a broader conversation about this trend.

Rev. Carlos L. Malavé, the organizer of the event and president of the Latino Christian National Network, told Religion News Service that Christian Nationalism had “infiltrated” some parts of the Latino Christian community “in such a powerful way that they are not even aware of the position they are supporting.”

Other voices entering the conversation in new ways include environmentalist (and lay Methodist) Bill McKibben. In a recent piece for The New Yorker, he lamented the threat Christian Nationalism poses to American society and noted the power of clergy to influence this debate: “They are insiders who can say that the current incarnation of Christian power is not, in fact, particularly Christian — who can, among other things, scoff at their brethren’s sense of victimization and point out that they are not, in fact, the targets of discrimination.”

Andrew Whitehead, a sociologist and one of the country’s leading scholars of Christian Nationalism, is also releasing a new book this summer. Rather than writing in the dispassionate voice of a social scientist, he’s using his expertise in service to the Church. His book’s title makes clear the severity of the stakes: American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church.

Finally, there’s the voice of Susan Stubson, a self-identified evangelical Christian and a leader within the Republican Party of Wyoming. In an essay for the New York Times last month, she testified to the damage Christian Nationalism was inflicting on her state, her political party, and her Christian faith.

“I am adrift in this unnamed sea, untethered from both my faith community and my political party as I try to reconcile evangelicals’ repeated endorsements of candidates who thumb their noses at the least of us,” she wrote. “Christians are called to serve God, not a political party, to put our faith in a higher power, not in human beings. We’re taught not to bow to false idols. Yet idolatry is increasingly prominent and our foundational principles — humility, kindness, and compassion — in short supply.”

That reality shows why good preaching matters more than ever. Christian Nationalism is a lot of things, but it’s not good news.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood