The fastest growing religious group in the United States is the “nothing in particulars,” or the Nones. The rise in those disaffiliating from organized religion has led to a lot of anxiety and hand-wringing by those whose job involves organizing religious communities, aka pastors.

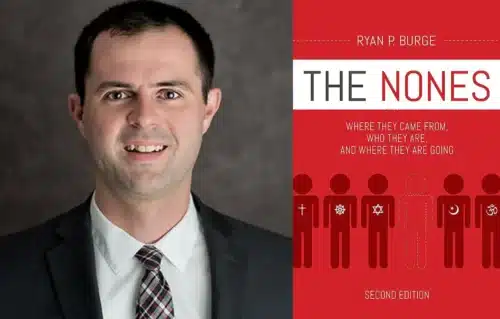

Into this angst comes the second edition of Ryan Burge’s The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going (Fortress, 2023). Animating this book is the premise that such a large group representing a tectonic shift in American religious life needs to be understood. And, secondarily, that Christians interested in reaching the nones in the hopes of gaining a second hearing for their faith can’t do so until they first comprehend who the nones are (and aren’t).

To foster this understanding, Burge draws on his training as a political scientist. He uses survey data and basic social science methods to explain trends in religious identification, offer a demographic snapshot of the nones, and suggest possible explanations for their dramatic rise.

I’ve previously written about Burge’s penchant for making data about religion and politics digestible to the statistical layperson. This volume exemplifies that talent as he skillfully presents data in ways that clarify rather than confuse. Simply put, this book is the place to start if someone wants to grasp the exodus of people from our churches.

Burge rightly notes that a phenomenon this complicated is unlikely to have simple explanations, but he does name one likely culprit. Political polarization is driving people away from religion, as our faith identities are increasingly defined by partisan loyalties.

“[T]he connection between identifying as a political liberal and having no religious affiliation has grown over time, while political conservatives are still overwhelmingly people of faith,” he wrote. “This is subconsciously conveying the message to Americans that to be religious is to be a conservative Republican, while to be nonreligious is to align with the Democrats and liberals.”

Even as Burge leverages his academic expertise in exploring this topic, he is not a disinterested scholar. He is also an American Baptist pastor with a long history of serving local congregations. He studies an experience he has observed and lived.

Thus, Burge concludes the book by suggesting how Christian leaders and communities should respond to the rise of the nones. His advice is not pollyannaish. He does not provide easy answers. Religious disaffiliation is not likely to abate. It is driven by large forces like globalization and secularization that are impossible to reverse.

Still, he does suggest some initial steps. Large surveys provide a snapshot of the population sampled but they offer little in terms of nuance or explanation. Yet, Burge notes that “every single row on my spreadsheet represents a human being who has a story to tell.”

The place to start is by listening to the stories of the nones to understand the various reasons they identify as they do. Some of those narratives will be unrevealing but others will illuminate the ways churches and the Christians within them have alienated people whose identities and questions weren’t welcome and the way structural forces in our society make it difficult for participation in a faith community to become an important part of someone’s life.

Burge’s intuition here resonates with the work of another social scientist studying those who have left organized religion. In Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America, Stephen Bullivant approaches this phenomenon from a qualitative perspective. He interviewed dozens of people who previously claimed a faith tradition but now explicitly do not identify with one. His research also emphasizes the value of hearing the stories told by these nonverts.

“Reaching the point where you no longer identify with any religion, even nominally, will naturally be a rather different journey if you were brought up in a Black Pentecostal family in the Sunbelt than if you were raised a middle-of-the-road Episcopalian in New England,” Bullivant explained. “But it won’t just be the starting point and route that are different. So too, in all likelihood, will the destination be. That is, your personal brand of nonreligiosity — your ‘noneness’ — will be very different from that of your WASP-ish doppelganger.”

We are living through a transformational moment in American religious life that is defined by an exodus of people from organized religious communities. Who those former adherents are and why they are choosing to exit now are complicated topics. A fundamental premise of social science is that its methods depict things as they are — not as we might desire them to be.

Learning from those who have mastered those tools and are focused on this sea change is an important and necessary first step that must precede any attempt to craft solutions to this challenge. That’s why we’ve had Burge on our Dangerous Dogma podcast (and we’ve had Bullivant on as well).

Ryan Burge’s updated edition of The Nones is the entry point most of us need into this complex conversation. That’s why we’re not just recommending you read his book; we’re going to give away a signed copy of The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going to a paid subscriber of A Public Witness. We’ll be picking that winner later this week, so upgrade your subscription today to ensure you’re eligible to win.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood