(RNS) — Over the past two years, a group of influential evangelical leaders broke away from their churches or denominations, mostly over their congregations’ solid support for former President Donald Trump and, more generally, conservative politics and messaging.

The moves, by such people as theologian Russell Moore and Bible study teacher Beth Moore, most prominently, but others as well, suggested deepening cracks between established evangelical leaders and ordinary believers.

Photo by Matt Botsford/Unsplash/Creative Commons

But a new study published in the latest issue of Politics and Religion, a quarterly journal, shows there’s no evidence that white evangelical clergy are less conservative politically than their congregations. In fact, the survey found, white evangelical clergy are as conservative, if not more so, as the people in their pews.

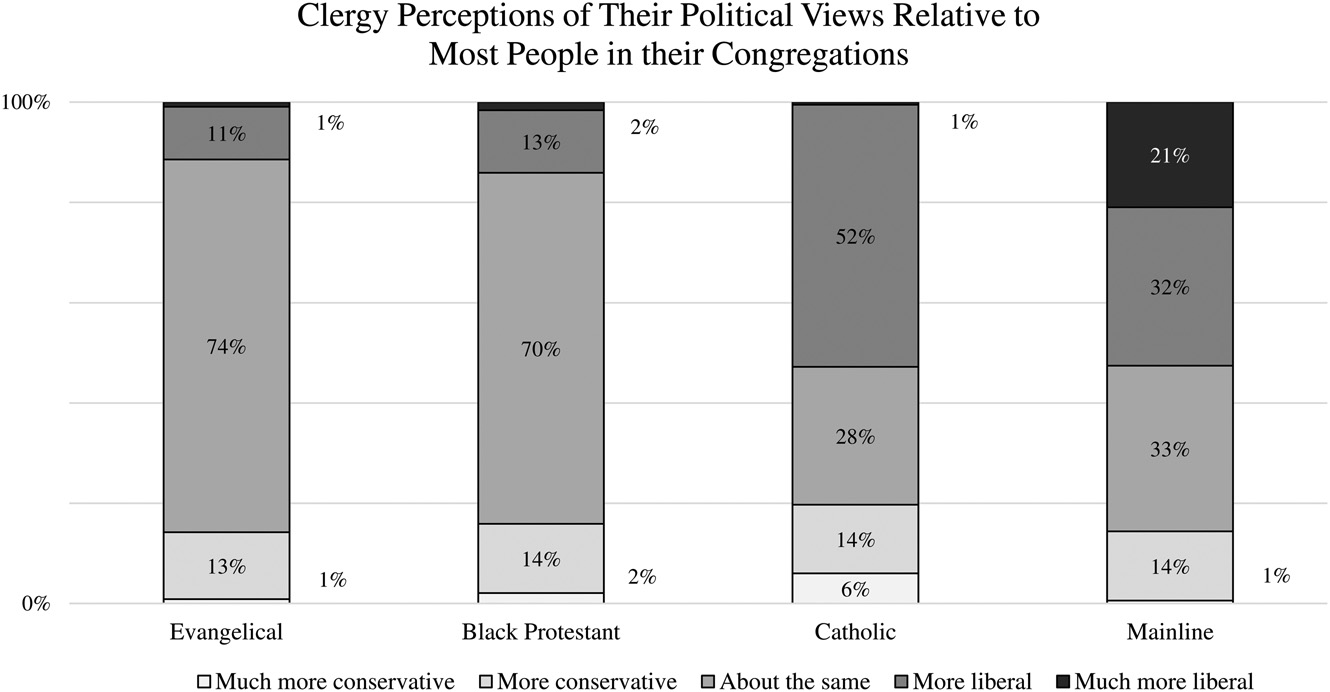

The study, by Duke University sociologist Mark Chaves and postdoctoral research associate Joseph Roso, finds that 74% of white evangelicals reported that their political views were about the same as most people in their congregations. (Only 12% of white evangelical clergy said they were more liberal than their congregants, and 13% said they were more conservative.)

“It really counters this idea that there are a lot of evangelical clergy who are more liberal than their people,” said Chaves.

“Clergy Perceptions of Their Political Views Relative to Most People in their Congregations” Graphic via Cambridge University Press

(The only other group where clergy and congregants neatly align is Black Protestants; 70% of Black clergy said they hold the same views as their congregants. But unlike white evangelicals, Black clergy, and churchgoers are far more liberal and tend to vote for Democrats.)

Consistent with decades of past data, the new study also shows a deep political gap between the views of clergy in more liberal Protestant denominations as well as the views of Catholic priests and their parishioners.

More than half (53%) of mainline Protestant clergy say they are more liberal or much more liberal than their congregants. Among Catholic priests, 52% said they were more liberal than their parishioners.

The study relies on data from the National Survey of Religious Leaders conducted in 2018-2019, and the 2018 General Social Survey. The survey included responses from leaders across many religious traditions, but the study focused on a sample of 846 Christian clergy arranged in four different groups: Evangelicals, Black Protestants, mainline Protestants, and Catholics.

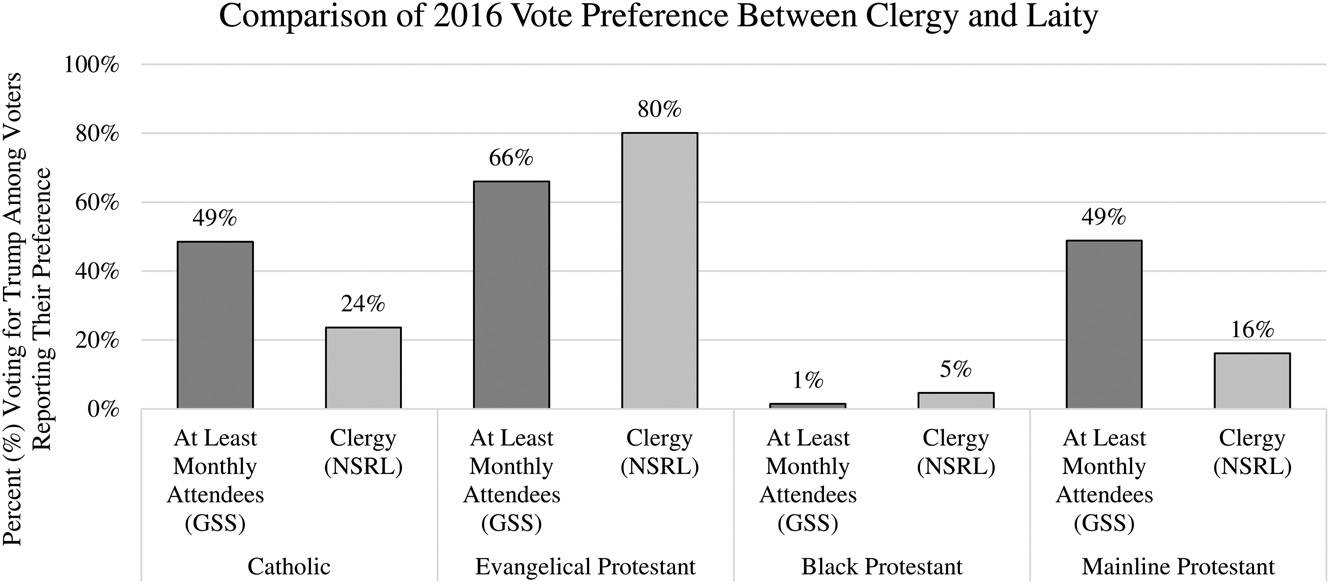

Those clergy were asked, “How would you compare your own political views to those held by most people in your congregation?” They were then asked who they voted for in the 2016 presidential race between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. Researchers then compared those answers to data from the General Social Survey on how monthly churchgoers in those four Christian groups voted for Trump in 2016.

“Comparison of 2016 Vote Preference Between Clergy and Laity” Graphic via Cambridge University Press

Chaves pointed out that mainline Protestants have been considerably more liberal than their congregants for a long time — dating back to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s when many mainline clergy spoke out in support of justice and equality for Blacks and later publicly opposed the Vietnam War.

What isn’t clear from the study is whether evangelical pastors have long been politically aligned with their congregants or if that’s a more recent phenomenon. (Chaves said there’s no good national representative surveys to document that.)

The survey suggests clergy who are more in sync with their congregants find it easier to mobilize as a political base into a potent constituency. And of course, white evangelicals have become arguably the most influential voting bloc in the Republican Party.

Many evangelical pastors have embraced politics, railing about perceived threats from the secular world and using social media to expand their reach.

“It speaks to why the religious right is more politically effective,” said Chaves. “The more liberal-leaning clergy are in churches where the people aren’t with them.”

The study did not speculate on why white evangelicals were much more likely to be on the same page politically with their church members, but Paul Djupe, a political scientist at Denison University, said there were probably a few reasons.

White evangelical pastors are more likely to lead congregational type churches, where members choose their own ministers. In mainline and Catholic churches, clergy are often chosen by bishops or others in the denominational hierarchy one step removed from the local congregation.

Evangelical pastors may also have less seminary education than mainline or Catholic clergy.

“The very fact of going through higher education to get a master’s or even a doctorate in theology is something that probably makes them more liberal, or gives them an expansive view on a number of issues,” Djupe said of mainline and Catholic clergy.

That education may also lend mainline and Catholic clergy a wider lens on social justice issues from a national or global perspective.

By contrast, Djupe said, “evangelicals are thinking about the community and how to preserve the community, which are traditionally conservative notions.”

But Djupe said it would be a mistake to suggest mainline or Catholic clergy avoid political issues because their congregants are more divided.

“They might be a little bit more careful about how they talk about those issues, but they still talk about more issues than evangelicals do,” Djupe said.

The study did not address the relationship between congregation size and clergy political activism. The larger a church, the more likely it includes a diverse set of participants.

“Based on our analysis, it does not appear that pastors of large congregations differ substantially in their political involvement from pastors of smaller congregations,” Roso said.