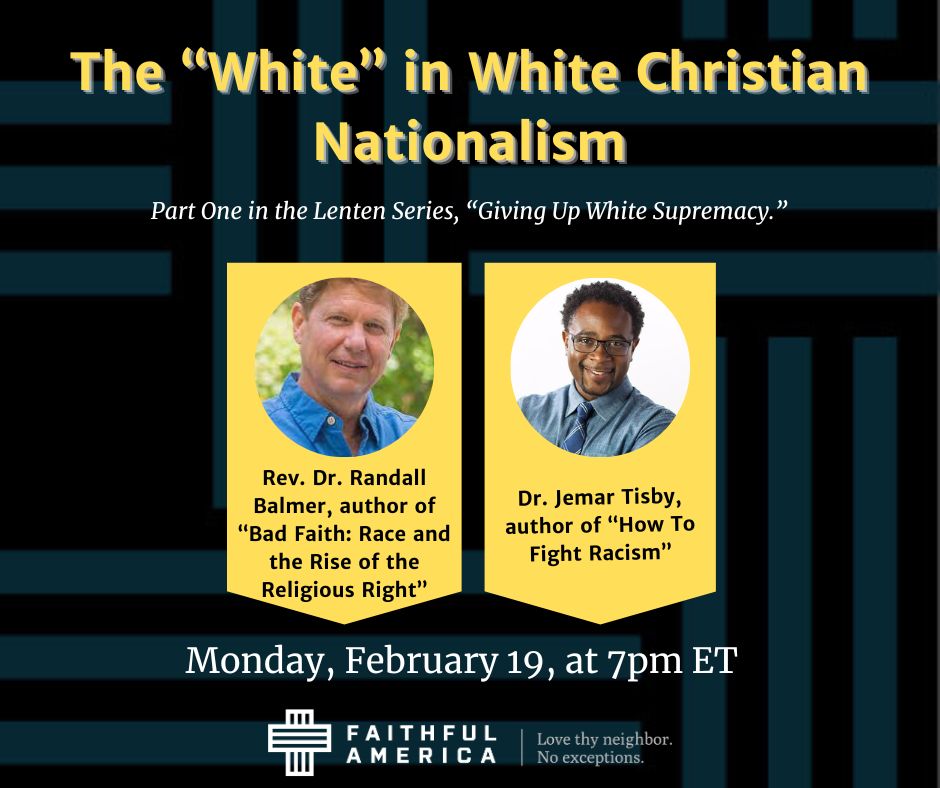

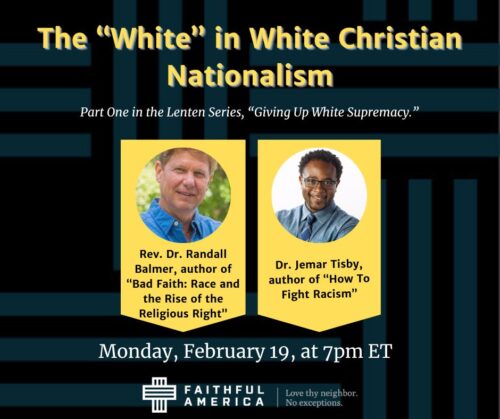

During this Lenten season, Faithful America is “giving up White Supremacy.” The large, multi-denominational online Christian community is accomplishing this through offering a three-part webinar series that launched on Monday (Feb. 19). This inaugural session, titled “The ‘White’ in White Christian Nationalism,” featured Dr. Jemar Tisby (author of How to Fight Racism) and Rev. Dr. Randall Balmer (author of Bad Faith: Race and the Rise of the Religious Right).

“As Christians across many traditions begin the Lenten journey, we are called to reflect on our shared humanity, our sins, and our own roles in perpetuating injustices in our communities,” said moderator Rev. Nathan Empsall, executive director of Faithful America. “It’s imperative — especially during this election year — that our faith communities confront the shadows of White Christian Nationalism in our churches and society.”

Most people studying religion in the United States have come to understand Christian Nationalism as an ideology that demands a fusion of American civic life with conservative Christianity. So what is the difference between White Christian Nationalism and “standard” Christian Nationalism?

“They’re basically the same thing,” said Empsall. “Sometimes I say that White Christian Nationalism is the biggest subset of Christian Nationalism. Our friends at the group Christians Against Christian Nationalism say that Christian Nationalism gives cover to and helps propagate White supremacy … Even when we say just Christian Nationalism, not White Christian Nationalism, it’s vital that we still point out the racism inherent to Christian Nationalism in the American context.”

To further elaborate this point, Tisby noted that in The Flag and the Cross, sociologists Philip Gorski and Samuel Perry explore how Christian Nationalistic beliefs are connected to upholding a political order where “Christian” is linked to rightwing understandings of gender and racial norms. They concluded, “The United States cannot be both a truly multiracial democracy — a people of people and a nation of nations — and a White Christian nation at the same time.”

Tisby himself defined White Christian Nationalism as “an ethnocultural ideology that uses Christian symbolism to create a permission structure for the acquisition of political power and social control.” He regards it as the biggest threat to both democracy and the church.

“The greatest threat to democracy because it seeks to have this authoritarian power that defies the will of the people. And,” he explained, “it’s the greatest threat to the witness of the church today because of the way it’s repelling people from Jesus. It’s causing folks to run away from the church because they look at White Christian Nationalism and they think that’s what Christianity is about — and they want nothing to do with it, quite understandably.”

Echoing much of this sentiment, Balmer focused his discussion on the origins of the United States and the birth of the Religious Right.

“This notion that the United States is and always has been a Christian nation really falters on two grounds: heresy and history,” he said.

Balmer expertly wove together the history of Roger Williams giving us the metaphor of the garden of the church being separated by a wall from the wilderness of the state, the reality that none of the founders (except maybe Benjamin Rush and John Witherspoon) would be welcome in the contemporary churches advocating for Christian Nationalism, and the Treaty of Tripoli explicitly stating with unanimous approval from the U.S. Senate in 1797 that “the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”

Then why have there been numerous failed attempts to rewrite this history, from a so-called “Christian Amendment to the Constitution” during the Civil War to the backlash over the 1962 U.S. Supreme Court decision holding that reciting government-written prayers in public schools was unconstitutional? Balmer chalks this up to the power of nostalgia.

“Especially in the early years of the Religious Right, there was a lot of pining for the 1950s,” he said.

And this is intertwined with what he describes as the myth that conservative evangelicals galvanized as a political movement in direct response to the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. After noting that the Southern Baptist Convention supported abortion rights until 1976 and Jerry Falwell did not preach against abortion until 1978, Balmer made the case that “it was only in the late 1970s in advance of the 1980 presidential election that they attached themselves to the abortion issue. It was not an issue before that.”

The issue that actually birthed the Religious Right as the political force we know today was a 1971 district court ruling determining that any organization engaged in racial segregation was by definition not a charitable organization and should therefore lose tax-exempt status. Conservative evangelical leaders like Paul Weyrich mobilized behind overturning this desegregation measure that they saw as a threat to Christian education — and a direct challenge to what we would now label White Christian Nationalism.

Despite the heaviness of this topic, the question and answer section that followed the primary discussion ended on a note of hope.

“The longer I’m in this work, particularly of racial justice, the more I learn that the victory is in the process,” Tisby said. “The victory is in the journey. The victory is not simply in laws passed or policies changed. It’s in how we ourselves are changed. So, what gives me hope is seeing people who are changed and transformed in simply the act of pursuing justice and doing the right thing.”

“As a Christian, and as a parent, I don’t have the luxury of despair,” Balmer added. “I have to be hopeful. Despair is a cop-out I think in some ways, and we have to find reasons to be hopeful. And we have to work to actualize — to realize — that hope.”

This webinar was the most attended in the history of the organization with nearly 1,000 people watching live. This beat the previous record attendance that was set during a recent discussion of the new documentary God & Country with producer Rob Reiner.

Part two of the series is “Taking the Log Out of Our Own Eyes,” featuring a conversation about white supremacy within Catholic and mainline Protestant traditions with Rev. Dr. Gayle Fisher-Stewart, editor of Preaching Black Lives (Matter). The final webinar in the series will be focused on offering spiritual exercises for racial justice. The full list of future participants as well as when the two remaining webinars are to be held will be released by Faithful America at a later date.