(RNS) — After the departure of thousands of traditionalist United Methodist churches from the denomination over the past five years, it might stand to reason that those congregations remaining in the fold are more progressive and open to ordination and marriage of people in same-sex relationships.

A group of clergy and laity in the United Methodist Church North Carolina Conference gathers for a Rally of Inclusion in the parking lot of the conference office on March 28, 2019. (Photo courtesy of UMC NC Conference)

But the picture is far more mixed.

A new report from the Religion and Social Change Lab at Duke University that looked at disaffiliating clergy from North Carolina’s two United Methodist conferences or regions found that even after the departures, 24% of North Carolina clergy remaining in the denomination disagree with allowing LGBTQ people to get married and ordained within the denomination.

“…at least some amount of ambivalence over LGBTQ+ issues among UMC clergy is likely to persist for years to come,” the report concluded.

After a four-year COVID-19 delay, and the departure of about 7,600 U.S.-based churches — a loss accounting for 25% of all its U.S. congregations — the denomination is likely to reconsider the issue of human sexuality when it convenes its top legislative body April 23-May 3 in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Among its agenda items will be removing restrictive LGBTQ passages from the rule book, the Book of Discipline, which views homosexuality as “incompatible with Christian teaching” and forbids ordaining LGBTQ clergy or allowing clergy to officiate at same-sex weddings in the church.

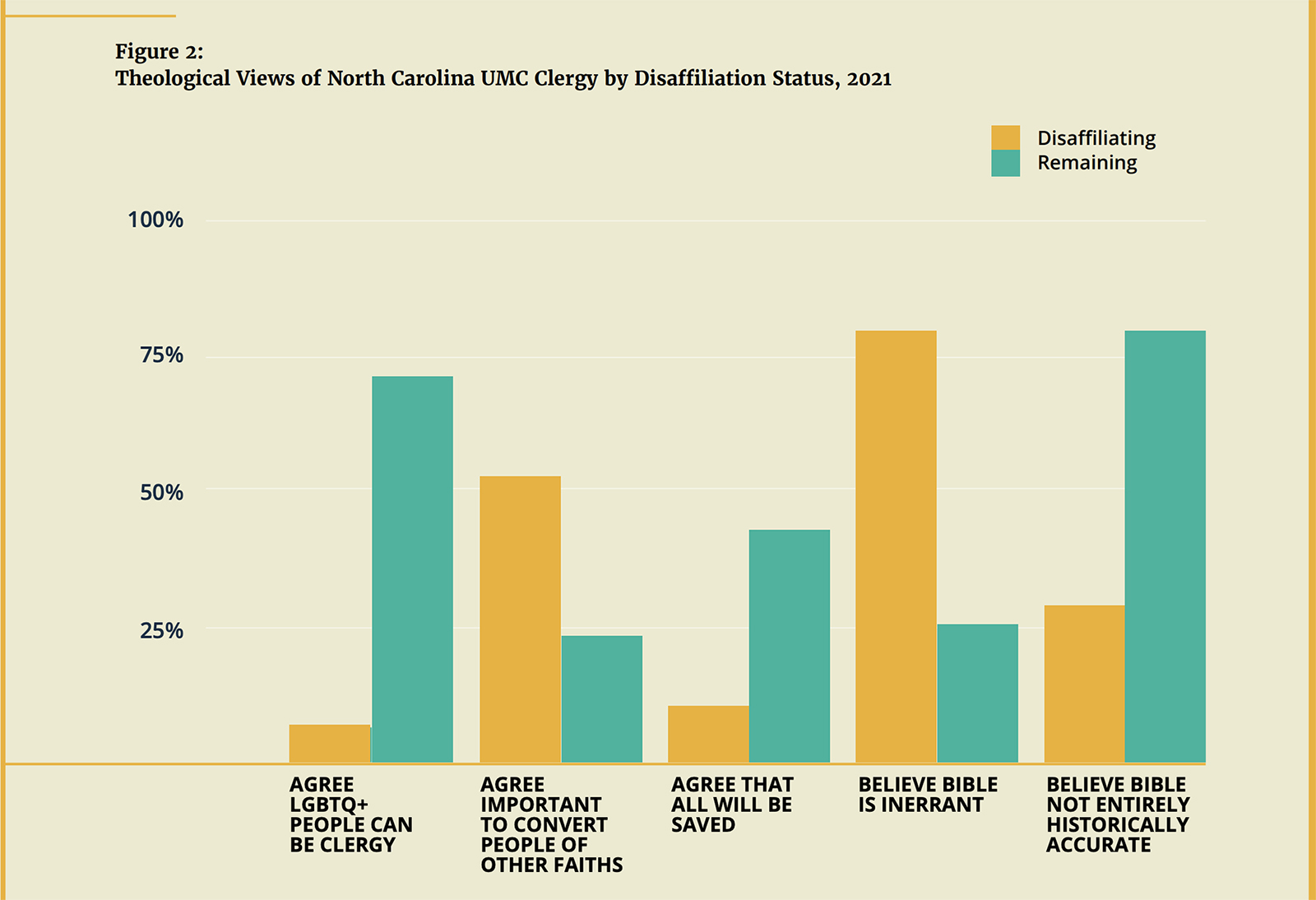

“Theological Views of North Carolina UMC Clergy by Disaffiliation Status, 2021” (Graphic courtesy Duke University)

Given that the denomination is a worldwide body, with hundreds of delegates from Africa and the Philippines, areas far more conservative in their views of human sexuality, it’s unclear whether the measures stand a chance of passing, even as the U.S. delegation is far more open to such changes.

Overall, the Duke report finds that disaffiliating North Carolina clergy were much more politically and theologically conservative than remaining clergy. Some 85% of clergy who left the denomination disagreed with the notion that “all religious leadership positions should be open to people in same-sex relationships.”

Those leaving clergy members tended to be more homogeneous in their beliefs and to lead somewhat smaller and more rural churches. Nearly all (94%) of leaving clergy were white. More than a fourth of leaving clergy — 26% — were licensed local pastors, meaning they were not ordained and had less advanced ministerial training.

But the report paints a picture of a reconstituted denomination that, at least in North Carolina, is politically and theologically diverse. Based on clergy’s assessments of their own congregations, 59% of remaining congregations were evenly divided between Republican and Democratic parties, 2.2% lean Republican, and 18% lean Democratic.

“It would be a mistake to say that the denomination in the U.S. has moved to being virtually uniformly progressive,” said Lovett Weems, director of the Lewis Center for Church Leadership at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C., who did not consult on the report. “Clearly, those who left were almost universally conservative politically and theologically. But those staying show a more mixed picture.”

Cover of the report “Disaffiliation from the United Methodist Church in North Carolina.” (Courtesy image)

A total of 671 churches across North Carolina left the United Methodist Church (325 congregations in the North Carolina Conference, covering the eastern half of the state, and 346 congregations in the Western North Carolina Conference, covering the western half). The report was based on the two conferences’ updated clergy records and compared with a 2021 longitudinal survey of clergy.

Those churches accounted for some 139,361 members and thousands of others who attended regularly or sporadically.

The Southeastern region of the U.S. has the most United Methodist churches, with Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Mississippi, and Tennessee vying for the most.

The study also showed that 59% of North Carolina pastors staying in the denomination said they are at least somewhat more liberal than most people within their congregation.

“For a long time, studies have shown that clergy in mainline denominations tend to be a bit more liberal than their membership. And this just kind of takes it one step further,” said Weems. “We should recognize that the denomination is still more middle of the road than on the progressive end of things.”

The report also showed that compared with disaffiliating clergy, remaining clergy report more symptoms consistent with depression, anxiety, burnout, and occupational stress.