(RNS) — A volunteer Southern Baptist task force charged with implementing abuse reforms in the nation’s largest Protestant denomination will end its work next week without a single name published on a database of abusers.

A cross and Bible sculpture stand outside the Southern Baptist Convention headquarters in Nashville, Tennessee, on May 24, 2022. (AP Photo/Holly Meyer, File)

The task force’s report marks the second time a proposed database for abusive pastors has been derailed by denominational apathy, legal worries, and a desire to protect donations to the Southern Baptist Convention’s mission programs.

Leaders of the SBC’s Abuse Reform Implementation Task Force say a lack of funding, concerns about insurance, and other unnamed difficulties hindered the group’s work.

“The process has been more difficult than we could have imagined,” the task force said in a report published Tuesday (June 4). “And in truth, we made less progress than we desired due to the myriad obstacles and challenges we encountered in the course of our work.”

To date, no names appear on the “Ministry Check” website designed to track abusive pastors, despite a mandate from Southern Baptists to create the database. The committee has also found no permanent home or funding for abuse reforms, meaning that two of the task force’s chief tasks remain unfinished.

Because of liability concerns about the database, the task force set up a separate nonprofit to oversee the Ministry Check website. That new nonprofit, known as the Abuse Response Committee, has been unable to publish any names because of objections raised by SBC leaders.

“At present, ARC has secured multiple affordable insurance bids and successfully completed the vetting and legal review of nearly 100 names for inclusion on Ministry Check at our own expense with additional names to be vetted pending the successful launch of the website,” the task force said in its report.

Josh Wester, the North Carolina pastor who chairs the ARITF, said the Abuse Response Committee — whose leaders include four task force members — could independently publish names to Ministry Check in the future but wants to make a good-faith effort to address the Executive Committee’s concerns.

Task force leaders say they raised $75,000 outside of the SBC to vet the initial names of abusers. That list includes names of sexual offenders who were either convicted of abuse in a criminal court or who have had a civil judgment against them.

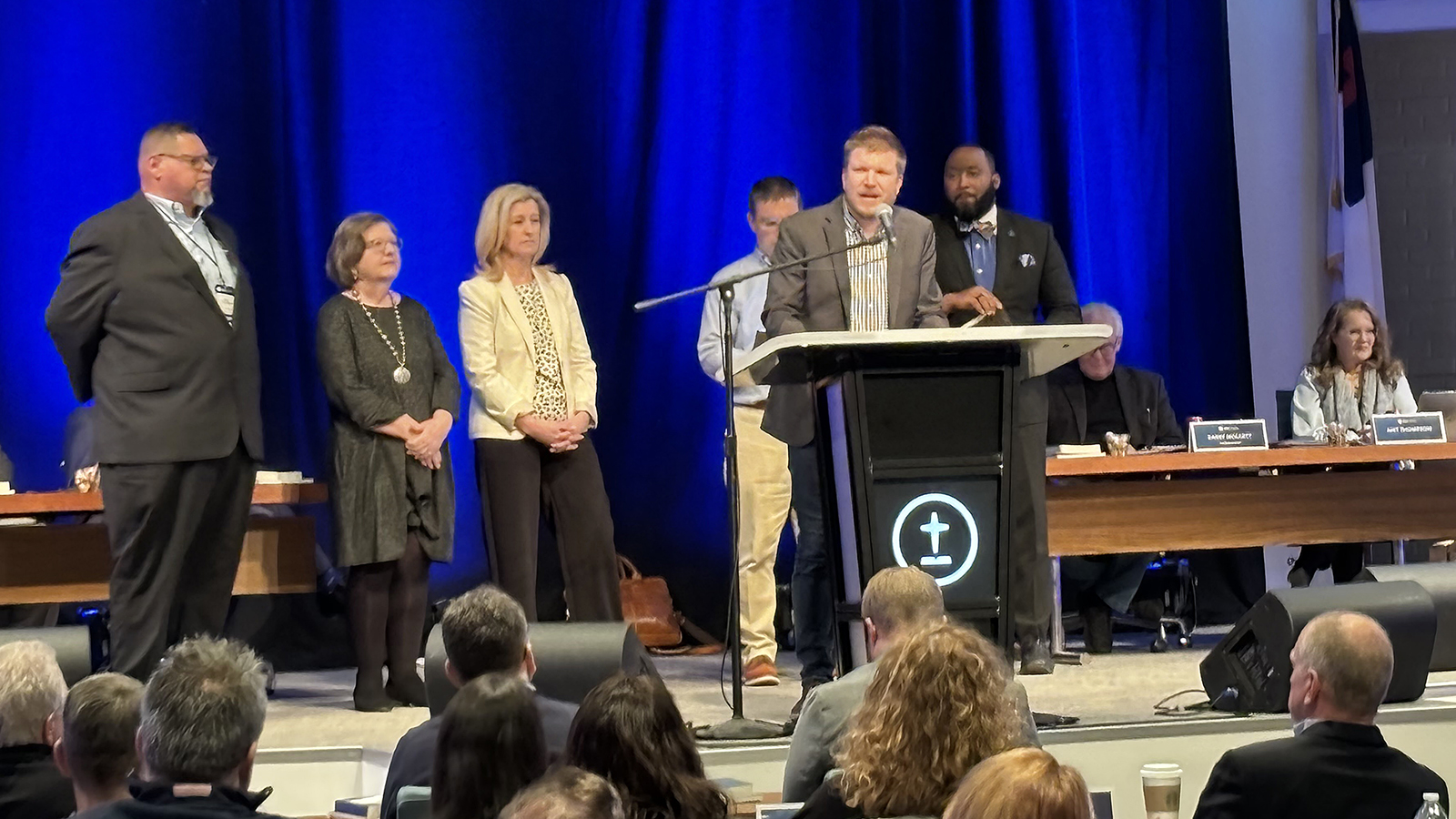

North Carolina pastor Josh Wester, chair of the SBC’s Abuse Reform Implementation Task Force, with fellow members of the task force, speaks at the SBC Executive Committee’s meeting in Nashville, Tenn., Feb. 19, 2024. (RNS photo/Bob Smietana)

“To date, the SBC has contributed zero funding toward the vetting of names for Ministry Check,” according to a footnote in the task force report.

Earlier this year, the SBC’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission designated $250,000 toward abuse reform to be used by the ARITF. Wester hopes those funds will be made available to ARC for the Ministry Check site. The SBC’s two mission boards pledged nearly $4 million to assist churches in responding to abuse but have said none of that money can be given to ARC.

The lack of progress on reforms has abuse survivor and activist Christa Brown shaking her head.

“Why can’t a billion-dollar organization come up with the resources to do this?” asked Brown, who for years ran a list of convicted Baptist abusers at a website, StopBaptistPredators.org, which aggregated stories about cases of abuse.

Brown sees the lack of progress on reforms as part of a larger pattern in the SBC. While church messengers and volunteers like those on the ARITF want reform and work hard to address the issue of reforms, there’s no help from SBC leaders or institutions. Instead, she said, SBC leaders do just enough to make it look like they care, without any real progress.

Christa Brown talks about her abuse at a rally outside the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention at the Birmingham-Jefferson Convention Complex on June 11, 2019, in Birmingham, Ala. (RNS photo/Butch Dill)

“The institution does not care,” she said. “If it did care it would put money and resources behind this. And it did not do that. And it hasn’t for years.”

SBC leaders have long sought to shield the denomination and especially the hundreds of millions of dollars given to Southern Baptist mission boards and other entities from liability for sexual abuse. The 12.9 million-member denomination has no direct oversight of its churches or entities, which are governed by trustees, making it a billion-dollar institution that, for all intents and purposes, does not exist outside of a few days in June when the SBC annual meeting is in session.

As a result, abuse reform has been left in the hands of volunteers such as those on the task force, who lacked the authority or the resources to complete their task.

As part of its report, the ARITF recommends asking local church representatives, known as messengers, at the SBC annual meeting if they still support abuse reforms such as the Ministry Check database. The task force also recommends that the SBC Executive Committee be assigned the job of figuring out how to implement those reforms — and that messengers authorize funding to get the job done.

Church messengers will have a chance to vote on those recommendations during the SBC annual meeting, scheduled for June 11-12 in Indianapolis.

The task force’s report does include at least one success. During the annual meeting next week, messengers will receive copies of new training materials, known as “The Essentials,” designed to help them prevent and respond to abuse.

This is the second time in the past 16 years that attempts to create a database of abusive Southern Baptist pastors failed. In 2007, angered at news reports of abusive pastors in their midst and worried their leaders were doing nothing about it, Southern Baptists asked their leaders to look into creating a database of abusive pastors to make sure no abuser could strike twice.

Messengers vote during the first day of the Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center in New Orleans on June 13, 2023. (RNS photo/Emily Kask)

A year later, during an annual meeting in Indianapolis, SBC leaders said no. Such a list was deemed “impossible.” Instead, while denouncing abuse and saying churches should not tolerate it, they said Baptists should rely on national sex offender registries.

Because there is no denominational list of abusive pastors, local church members have to fend for themselves when responding to abuse, said Dominique and Megan Benninger, former Southern Baptists who run Baptistaccountability.org, a website that links to news stories about Baptist abusers.

The couple started the website after the former pastor at their SBC church in Pennsylvania was ousted when the congregation learned of his prior sexual abuse conviction. Before long, he was preaching at another church.

“We were just, like, how does this happen?” Megan Benninger said.

When the couple posted on Facebook about their former pastor, leaders of their home church reprimanded them, telling them in an email that they should not have made their concerns public. Not long afterward, the couple decided to set up a website that would collect publicly available information about abusive pastors.

“Our goal is to share information so people can decide whether a church is safe or not,” said Dominique Benninger.

To set up their site, the Benningers modified an e-commerce website design so that instead of sharing information about products, it shares information about abusive pastors. The website became a database of third-party information, which is protected by the same federal laws that protect other interactive computer services, like Facebook.

The Benningers don’t do any investigations but instead aggregate publicly available information to make it easier for church members to find out about abusers. That kind of information is needed, they say, so church members can make informed decisions.

The Benningers have recently placed a hold on adding new names to their database while Megan Benninger is being treated for cancer. They wonder who will pick up the slack if the SBC’s proposed database fails. They also are skeptical about claims that having a database would undermine local church autonomy — which is a key SBC belief.

“You are just warning them that there’s a storm coming,” said Megan Benninger. “How is that interfering with anyone’s autonomy?”

Members of the abuse task force say the denomination has made progress on abuse reforms in recent years but more remains to be done.

“We believe the SBC is ready to see the work of abuse reform result in lasting change,” the task force said in its report. “With the task force’s work coming to an end, we believe our churches need help urgently.”

Brown, author of “Baptistland,” an account of the abuse she experienced growing up in a Baptist church and her years of activism for reform, is skeptical that any real change will happen. Instead of making promises and not keeping them, she said, SBC leaders should just admit abuse reform is not a priority.

“They might as well say, this is not worth a dime — and we are not going to do anything,” she said. “That would be kinder.”