On Friday (Jan. 3), Speaker Mike Johnson stood before the U.S. House of Representatives on the opening day of the 119th Congress and read what he called “Thomas Jefferson’s prayer.” However, as first reported by A Public Witness, that’s not true. Other outlets followed in noting the problem with Johnson’s claim, which Monticello deems as “spurious.” Yet, while the speaker told a false story about the prayer, he didn’t invent it. And despite his history of using fake quotes to justify his Christian Nationalism, in this case he wasn’t misled by a conservative pseudo-historian like David Barton but by the progressive House chaplain.

Like a decades-long game of telephone, the tale of the so-called “Jefferson’s prayer” takes many twists, with appearances by George Washington, an Episcopal convention in Missouri, a promoter of Christian Nationalism at a group now trying to debunk the claim, a Catholic newspaper in New York, a library heist, and a Presbyterian chaplain. But through a survey of old newspaper articles, books, and other historical records, I pieced together the story. This issue of A Public Witness documents how an Episcopal prayer written after the third president’s death was quoted by a Southern Baptist layman in Congress to baptize a man who advocated for the “wall of separation” between church and state and famously cut the miracles of Jesus out of the New Testament.

Washington Before Jefferson

The prayer Johnson read to congressional members was written late in the 19th century, decades after Jefferson’s death. In a book on Anglican prayers, Episcopal priest and author Christopher Webber attributed the prayer to Rev. George Lyman Locke (1835-1919), a minister in Rhode Island. Others also note Locke wrote it, like Episcopal minister and liturgist Marion Hatchett, who wrote in a book on the historical development of Episcopal liturgy that Locke penned the prayer in 1882 at the encouragement of a commission member working on the 1892 edition of the Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer. But the prayer didn’t make it in that volume.

After years of lobbying, the prayer was added in 1928 and appears in the current 1979 version as a prayer “for our country.” There doesn’t appear to be any effort to connect the prayer to Jefferson for four decades after its inclusion in the Episcopal liturgical resource. But even before Episcopalians officially adopted it, many people claimed — without evidence — that a different president composed the prayer.

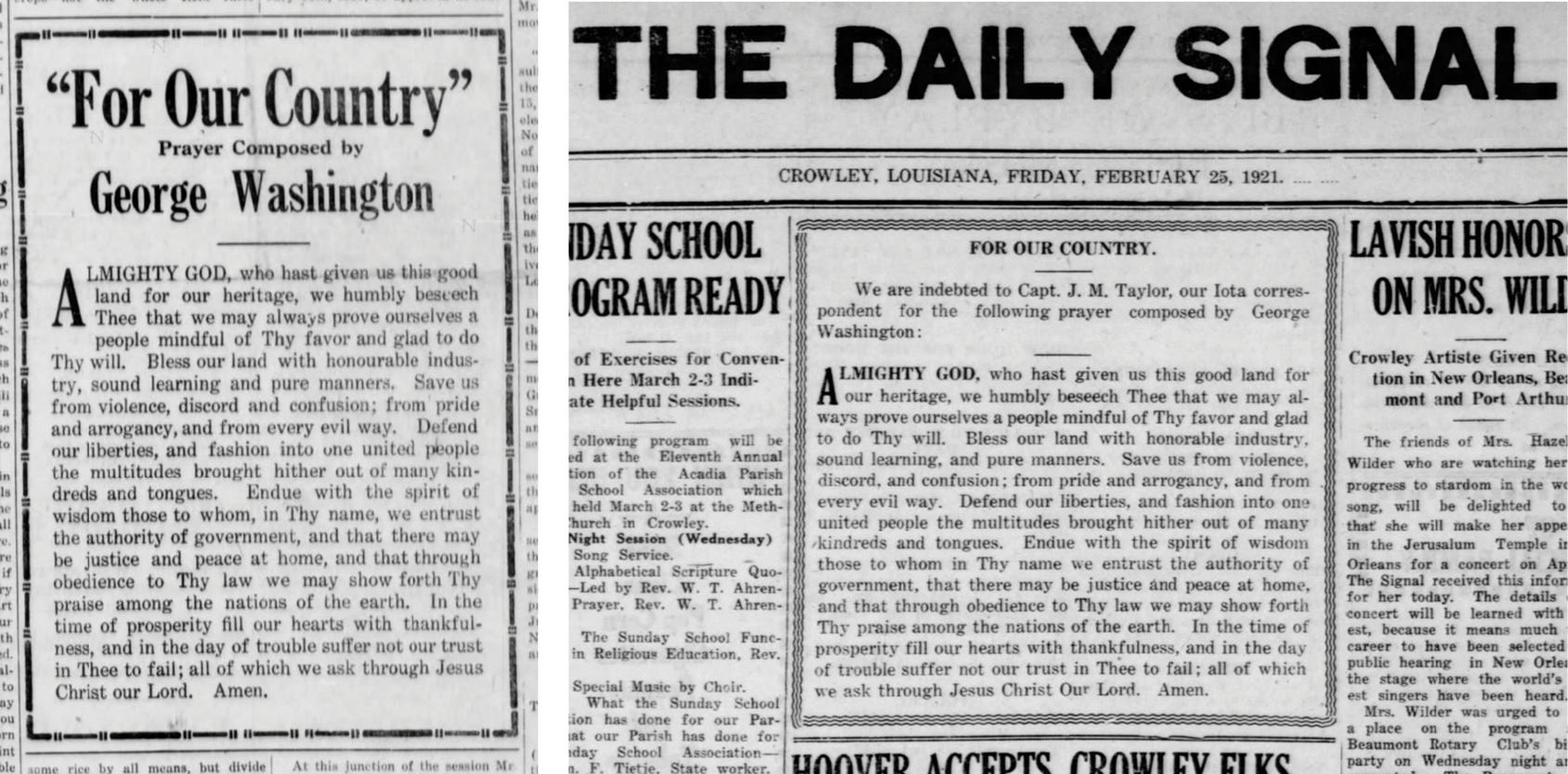

In 1921, three newspapers in Louisiana printed the prayer, titling it “For Our Country” with the note, “Prayer composed by George Washington.” The first two published it on the front page just after Washington’s birthday in February, with the other appearing in early March. The latter two papers added a bit of sourcing: “We are indebted to Capt. J.M. Taylor, our Iota correspondent for the following prayer composed by George Washington.” It’s unclear if Taylor simply sent them the first paper or served as the source for all three.

Left: Oakdale Journal of Feb. 24, 1921. Right: Crowley Daily Signal of Feb. 25, 1921.

The next year, at least 20 newspapers in 10 states printed the prayer as Washington’s. Most appeared on Washington’s birthday, with the others coming out shortly thereafter. Several put it on the front page and most simply called it a “prayer composed by” Washington and titled it “For Our Country.” A couple of publications added commentary to argue the prayer shows Washington’s Christian faith. For instance, the editor of the Duncan Weekly Eagle in Oklahoma wrote an introduction praising Washington as “the embodiment of the great virtues of man.” The editor added, “He was a sincere, God-fearing Christian. The following prayer, the product of Washington’s brain and thought, is characteristic of the man.”

After that burst of attention in 1922, the prayer sporadically appeared over the next few decades in various papers as written by Washington. Often, it showed up around his birthday or the Fourth of July, though it appeared a couple of times in December with the title of “A Christmas Prayer” or “A Holiday Prayer.” On several occasions, the prayer appeared in a letter to the editor as various readers sought to bring attention to the prayer as penned by Washington. None offered a source for the assertion that Washington wrote it.

Sometimes the prayer appeared in a piece as evidence of the Christian nature of Washington and the nation. Like the Feb. 22, 1958, issue of the Grand Haven Daily Tribune in Michigan, which argued that “George Washington’s prayer for mankind” shows “the religious background of our United States was firmly implanted by our first leaders.” Similarly, a letter to the editor in the Oct. 22, 1954, Springfield Union in Massachusetts praised President Dwight D. Eisenhower as “a man of God” put in power by “our Heavenly Father” and thus encouraged people to ask Democrats “if they can repeat the prayer made by George Washington every morning.” After including the text of the prayer, the writer added, “If every politician running for office cannot repeat that prayer without looking it up, do not vote for them.”

Occasionally during this time, the prayer was cited without attribution to Washington, especially as Episcopal ministers started using it after its addition to The Book of Common Prayer. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, an Episcopalian, read it to close his election-eve speech in 1940. But he didn’t attribute it to Washington, instead calling it “an old prayer which asks the guidance of God for our nation.” A few news reports of a prayer service at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., on the morning of Roosevelt’s inauguration in January 1941, quoted from the prayer as words from “the Episcopalian Litany.”

Despite the fact there’s no evidence Washington wrote the prayer and its composition instead came decades after his death, hundreds of newspaper accounts printed it as his prayer. As early as 1941, an Episcopal publication even tried to correct the record that Locke wrote it instead of Washington. But the error continued to spread. How did this misattribution occur? The answer might be found at an Episcopal meeting.

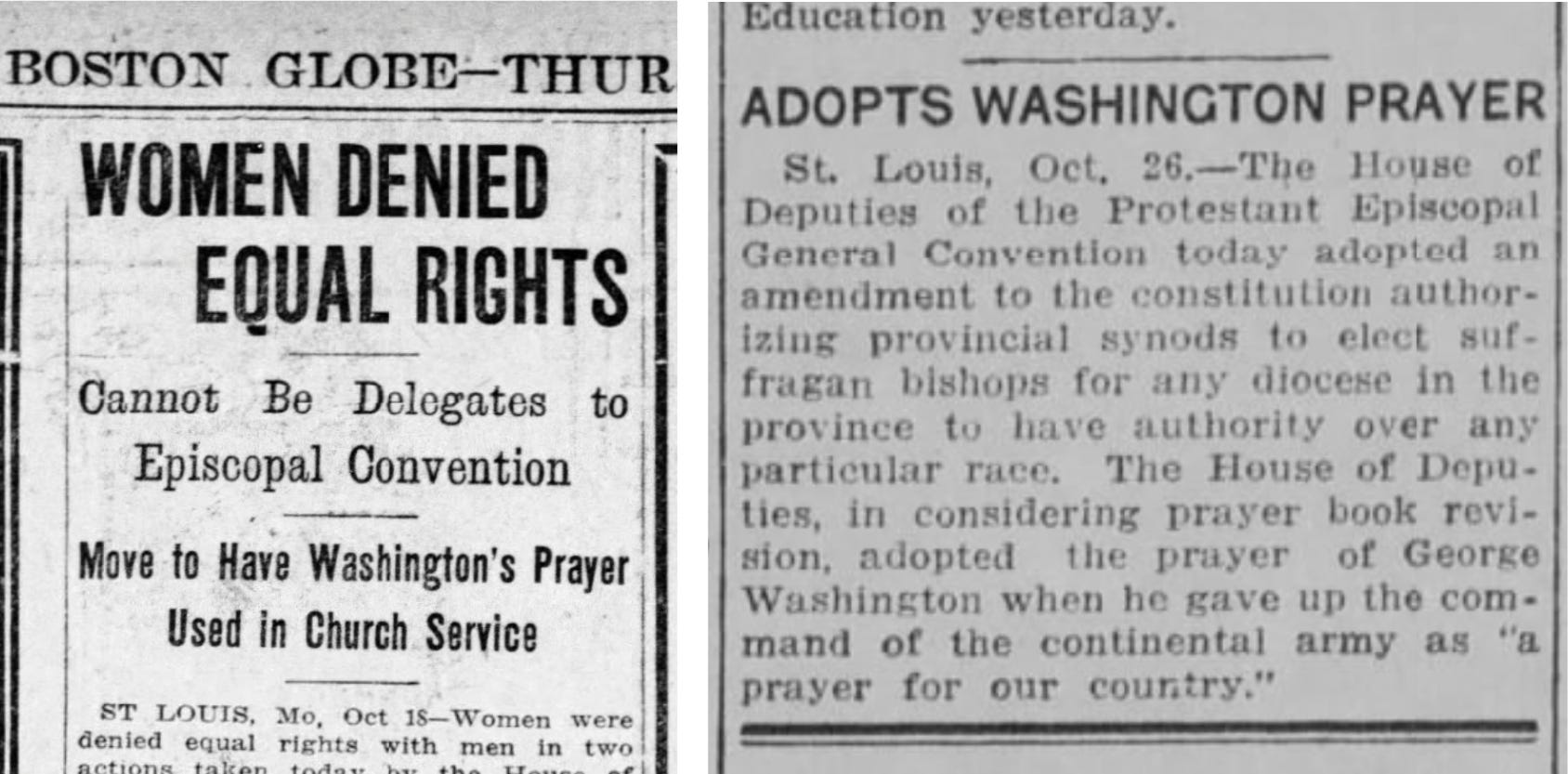

In October 1916, delegates to the Episcopal Church’s general convention gathered in St. Louis, Missouri. The big headline in papers across the country was “Women Denied Equal Rights” after delegates rejected a proposal to allow women to serve as delegates. But the issue receiving second billing was a debate about adding a prayer by Washington to The Book of Common Prayer. But it’s not the prayer Johnson read.

News reports note that a commission working on proposed changes had a recommended prayer “for our country” that matches the one now included. A delegate, however, urged replacing that one with a prayer Washington offered in a 1783 letter and which Mount Vernon still uses at its public wreath-laying ceremony. A few days later, newspapers reported that the delegates to the House of Deputies approved the recommendation to use Washington’s prayer (with slight edits) as the prayer “for our country.” However, it does not appear to have been approved by the House of Bishops. Thus, when the report from the commission came out three years later in 1919, they still recommended the prayer Johnson read to be the prayer “for our country” instead of one by Washington.

Left: Boston Globe of Oct. 19, 1916. Right: Wichita Beacon of Oct. 26, 1916.

In between the debate at the convention and the 1928 edition of The Book of Common Prayers, newspapers started printing the Episcopal prayer as composed by Washington but using the title the Episcopal commission was suggesting: “for our country.” Perhaps because of the news attention to Washington’s prayer being considered, someone mistook the other prayer actually recommended as the one Washington penned. Once printed as Washington’s, the claim spread and inspired others to similarly accept the prayer as composed by the nation’s first president.

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

From Washington to “Every Day” Jefferson

The shift from assigning authorship to Jefferson instead of Washington appears to have started in 1956 but really took off in 1962. The effort attempted to accomplish the same basic mission as the Washington tale: Cast the U.S. as Christian by “proving” the devotion of a key founder. Ironically, this occurs because of people associated with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation that owns and operates Monticello — and that today insists it is “spurious” to say the prayer is one written or recited by Jefferson.

The Charlottesville Daily Progress reported in 1956 that Rev. Herbert Donovan, the pastor of Christ Episcopal Church (which Jefferson gave funds to), read “Jefferson’s prayer for nation at luncheon.” The article included the full text of the Episcopal prayer and called it “Thomas Jefferson’s prayer for his country, taken directly from his own prayer book.” The Jefferson Foundation hosted the luncheon.

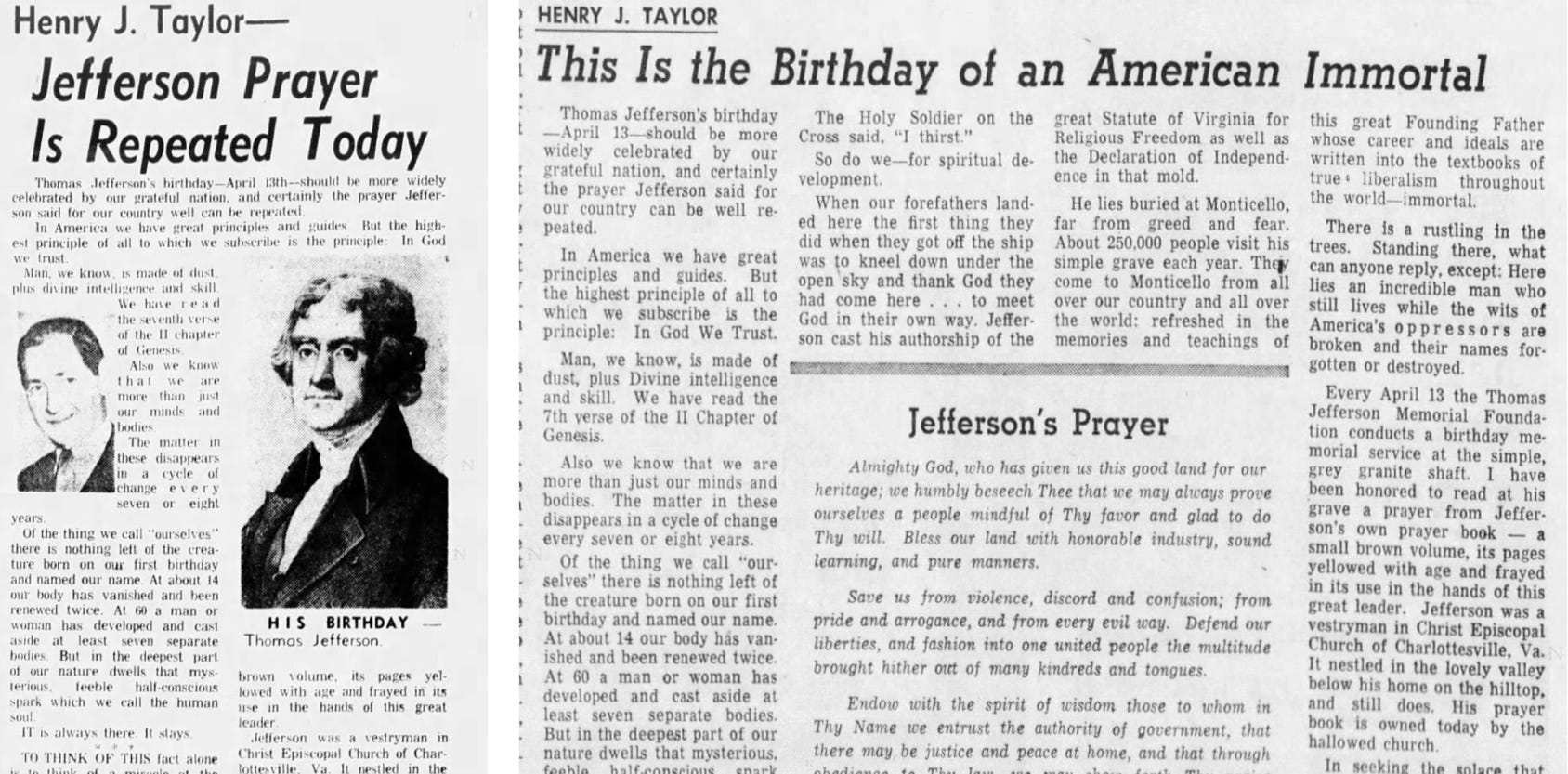

Other than minor reprinting shortly after the original piece, Donovan’s prayer claim doesn’t seem to spark more attention until it’s picked up six years later by a trustee of the foundation. Henry J. Taylor, who had recently finished serving as U.S. Ambassador to Switzerland during the second Eisenhower term, wrote an April 1962 column published in numerous newspapers through syndication. In it, he argued “the highest principle” in America is “In God We Trust.” Taylor then described Jefferson as an example of the nation’s “forefathers” following God.

“I have been honored to read at his grave a prayer from Jefferson’s own prayer book — a small brown volume, its pages yellowed with age and frayed in its use in the hands of this great leader,” Taylor wrote about the Bible owned by Donovan’s church. “In seeking the solace that can only come from prayer, in meeting the dark trails on the desperate early years of our republic, in carrying burdens of the Presidency for eight long years and to the day of his death, Jefferson turned to this book and said this prayer for his country.”

In most papers the column ended with the prayer, but the earliest one included another line from Taylor: “So spoke Thomas Jefferson.” A couple newspapers gave the prayer the title of “Jefferson’s Prayer.” Newspapers kept printing Taylor’s column near Jefferson’s birthday for two decades.

Left: Birmingham Post-Herald of April 13, 1962. Right: Wilmington Morning News of April 13, 1962.

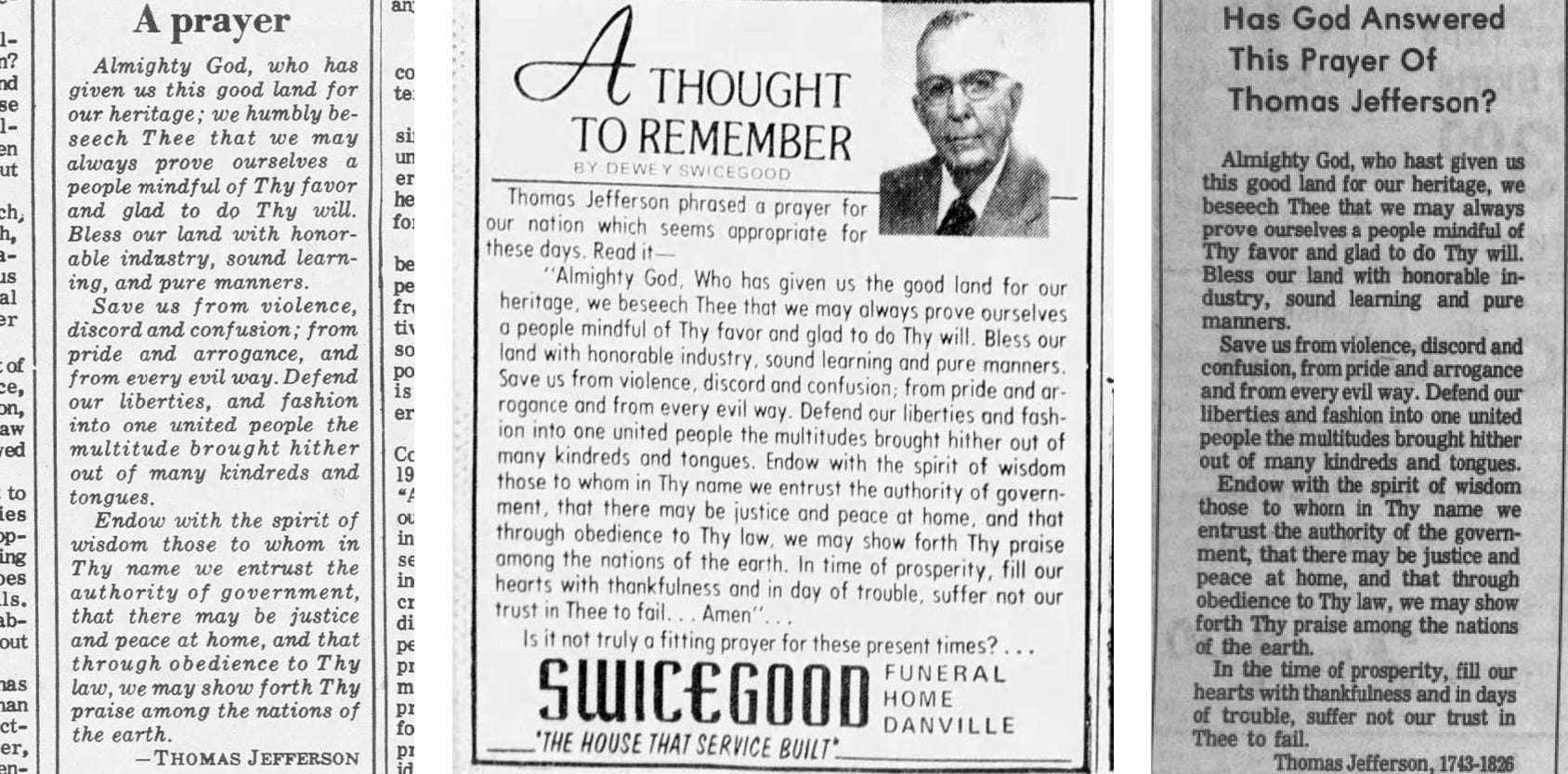

Not only did Taylor popularize the connection between Jefferson and the prayer, but he also used language close to Johnson’s last week about how “it is said each day of his eight years of the presidency, and every day thereafter until his death, President Thomas Jefferson recited this prayer.” However, Taylor didn’t actually assert that Jefferson read the prayer daily. After Taylor’s column, others offered wording even closer to Johnson’s. Patrick Scanlan, the conservative managing editor of The Tablet (a Catholic publication in New York), penned a column for the April 21, 1962, issue reflecting on Taylor’s syndicated column about Jefferson. Before printing the full prayer, Scanlan reworked Taylor’s language to make this claim: “Each day of his eight years of the Presidency, and every day thereafter until his death, Jefferson read this prayer.” That adds to what Taylor wrote, but it’s nearly identical to what Johnson read over six decades later. Scanlan highlighted the claim to show that the “great principles and guides” of “our distinguished forefather” were “founded upon religious ideals.”

Eventually, that assertion of daily reading spread, showing up in multiple pieces by different authors — including letters to the editors — around the Bicentennial celebrations in 1976. The various authors generally used the word “recited” like Johnson instead of “read” like Scanlan, and one July 4 letter in the Jackson Sun in Tennessee even started like Johnson did: “It is said…” Claims about Jefferson reciting it each and every day popped up in other publications over the following decades, as well as in remarks during legislative sessions in Michigan and Pennsylvania just before someone recited the prayer as that day’s invocation.

Though Taylor only claimed Jefferson read the prayer, that quickly morphed in numerous publications and speeches to assert that Jefferson wrote it. Conservative commentators like Bill O’Reilly and Bill Federer attributed the prayer to Jefferson like newspapers last century did to Washington. Historian Seth Cotlar recently compiled some of the conservative figures repeating the Jefferson prayer claims over the last few decades. Many of the pieces claiming Jefferson recited or wrote the prayer invoked the tale to push for more Christianity in government. Soon, just as had occurred for Washington, the prayer simply became known as “Jefferson’s prayer,” but attempts at providing a source for that claim didn’t last much after Donovan and Taylor. Like with Washington, the attribution to Jefferson was generally just accepted as if common knowledge.

Left: Canarsie Courier of Jan. 26, 1967. Center: Ad in Danville Register of Feb. 27, 1975. Right: Kosciusko Star-Herald of July 21, 1977.

The claim also shows up in the Congressional Record thanks to politicians quoting it, much as earlier members of Congress had invoked it as “Washington’s Prayer.” Republican Rep. John Zwach of Minnesota called it “Jefferson’s prayer” on Nov. 19, 1970, as did Republican Rep. Randy Forbes of Virginia on Feb. 4, 2013, during remarks on “our nation’s rich spiritual heritage” on behalf of the Congressional Prayer Caucus.

Although Donovan and Taylor helped create the connection between Jefferson and the Episcopal prayer, it’s not certain why they believed it was in his prayer book. As an Episcopal minister, Donovan would’ve surely been familiar with the prayer in The Book of Common Prayer. Today, the foundation the two men worked with while making the assertion calls the prayer a “spurious quotation” for Jefferson and highlights how it wasn’t published until after Jefferson’s death.

As for the prayer book Donovan and Taylor said contained the prayer, the Charlottesville Daily Progress offered an aside in a 1981 article about the church: “Thomas Jefferson’s prayer book was owned by Christ Church for many years. It was placed in Alderman Library at the University of Virginia, for safe keeping and subsequently stolen.” A University of Virginia magazine reported in 2019 on items stolen during an unsolved 1973 vault heist. Among the missing items was “Jefferson’s personal copy of the 1796 Book of Common Prayer.” That suggests the original effort to connect Jefferson to the Episcopal prayer may have occurred because someone saw that Jefferson had The Book of Common Prayer but then opened up a contemporary (and thus less fragile) copy to read a prayer from it while unaware that the prayer in question didn’t appear until 1928.

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

Congressional Prayer Service

After reports by A Public Witness and then other outlets about the inaccuracy of Johnson’s claim about “Jefferson’s prayer,” thousands of people criticized the speaker on social media for lying and making things up. Many suggested Johnson or his staff had been misled by conservative pseudo-historians like David Barton (who Johnson admits has influenced him). However, Johnson literally pointed to his source during his remarks.

“This morning I participated with many of you early this morning in the 119th Congress interfaith prayer service. It was held at St. Peter’s Catholic Church. … I was asked to provide a prayer for the nation. I offered one that is quite familiar to historians and probably many of us,” Johnson said before grabbing a piece of paper to read from. “It said right here in the program, it says right under my name, ‘It is said each day of his eight years of the presidency, and every day thereafter until his death, President Thomas Jefferson recited this prayer.’”

When Johnson made his claim about Jefferson, he was reading from a prayer service program. Although there don’t appear to be media reports from the service, some members of Congress and other attendees posted about it on social media, including sharing photos of Johnson speaking. A couple of them also identified who put the event together.

Democratic Rep. Joe Morelle of New York posted a photo of himself offering “a prayer for House staff.” He called the event “Chaplain Margaret Grun Kibben’s bipartisan prayer service.” A D.C. minister similarly mentioned the service was “conducted by the House Chaplain,” who does appear in photos from the service posted on social media. And Jason Rapert, a former Arkansas state lawmaker who leads a Christian Nationalistic group called the National Association of Christian Lawmakers, shared a photo of the front of the program like the one Johnson held up, which clearly shows the logo of the House chaplain’s office as the sponsoring body.

The 119th Congress Interfaith Prayer Service on Jan. 3, 2025, at St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Washington, D.C. (Facebook photo by Jason Rapert)

The false claim Johnson read from the podium of the U.S. House of Representatives came from a program printed and distributed by House Chaplain Kibben’s office for an event Kibben led. A minister in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and the first woman to serve as a congressional chaplain, Kibben was selected by then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi. Kibben’s third day on the job was the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection. She’s gained some attention for prayers that appeared to criticize Republican politicians trying to overturn the 2020 presidential election and attack lawmakers for not supporting a COVID-19 relief bill. She also pushes Christian Nationalism by justifying the practice of official government prayers and telling U.S. history in ways that privilege Christian prayer.

Kibben’s office did not respond to a comment request about the sourcing of the prayer claim in the program or if they would correct the record. Johnson’s office has also not responded to a comment request, so it’s unclear if he was familiar with the Jefferson prayer claims before reading the program.

After an exaggerated version of a false claim about Jefferson was printed in a program by the House chaplain’s office, the speaker of the House with a history of embracing fake quotes to justify Christian Nationalism and attack church-state separation gave the “spurious” claim its biggest platform. While many people on social media criticized Johnson for the claim, others shared it as truthful. This false claim, decades in the making, has received a new burst of support thanks to Chaplain Kibben and Speaker Johnson. It will now be easier for preachers and politicians to also bear false witness about Jefferson’s faith. For as Jefferson himself actually wrote, “He who permits himself to tell a lie once, finds it much easier to do it a second and third time.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor