NUUK, Greenland (AP) — Most Greenlanders are proudly Inuit, having survived and thrived in one of the most remote and climatically inhospitable places on Earth.

And they’re Lutheran.

About 90% of the 57,000 Greenlanders identify as Inuit and the vast majority of them belong to the Lutheran Church today, more than 300 years after a Danish missionary brought that branch of Christianity to the world’s largest island.

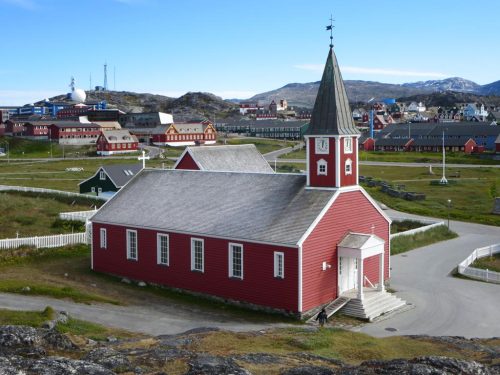

Nuuk Cathedral, built in 1849, is the head church of the Lutheran Diocese of Greenland. (David Stanley/flickr)

For many, their devotion to ritual and tradition is as much a part of what it means to be a Greenlander as is their fierce deference to the homeland. The one so many want U.S. President Donald Trump to understand is not for sale despite his threats to seize it.

Greenland is huge — about three times the size of Texas; most of it covered in ice. Still, its 17 parishes are located across many settlements in the icy land and people endure the frigid Arctic climate to fill up church pews on Sundays.

Some even tune in to radio-transmitted services on their phones on a break from fishing and hunting for seals, whales and polar bears, as their ancestors have done for generations.

That rugged yet vulnerable lifestyle helps fuel people’s devotion, said Bishop Paneeraq Siegstad Munk, leader of Greenland’s Evangelical Lutheran Church.

“If you see outside, nature is enormous, huge, and man is so little,” she told The Associated Press after a recent Sunday service in the capital city, Nuuk, where slippery ice covered the city’s streets.

“You know you won’t be able to survive by yourself,” she said.

That is, unless “you have faith,” she added. “God is not only in the building of the church but everywhere where he has created.”

Religiosity levels vary in Greenland as it does elsewhere. Sometimes being a member of the Lutheran Church here doesn’t mean one believes fully — or at all — in the church’s teachings, or even the presence of God.

Recently, Salik Schmidt, 35, and Malu Schmidt, 33, celebrated their wedding with family members, who joyously threw rice on them to wish them good fortune outside the red-painted wooden Church of Our Savior. Built in 1849, it is known as the Nuuk Cathedral.

Malu is spiritual but not religious; Salik is an atheist. Both said they’ll proudly belong to the Lutheran Church for life.

“Traditions are important to me because they pass on from my grandparents to my parents, and it’s been my way of honoring them,” Malu said later in their home while her sister babysat their daughter.

It also provides a sense of safety and permanence among change, Salik said.

“It’s something that is always there,” he said. “It brings joy to us.”

There are two Lutheran churches in Nuuk.

The Hans Egede Church is named for the Danish-Norwegian missionary who came to Greenland in 1721 with the aim of spreading Christianity, and who founded the capital city seven years later.

A short distance away stands the cathedral, and next to it, a statue of Egede remains on a hill in the Old District. In recent years, the statue was vandalized, doused with red paint and marked with the word “decolonize.”

Egede’s legacy is divisive. Some credit him for helping educate the local population and spreading Lutheranism, which continues to unite many Greenlanders under rituals and tradition.

“The positive side is that the church made people literate in less than a hundred years after the mission started,” said Flemming Nielsen, head of the University of Greenland’s theology department.

“When you can read, you use your skill for anything,” he said. “We have a rich Greenlandic literature starting at the middle of the 19th century. … It was the missionaries who invented a written language. And that is an important legacy.”

But for some, Egede symbolizes the arrival of colonialism and the suppression of rich Inuit traditions and culture by Lutheran missionaries and Denmark’s rule.

“His statue should be taken down,” wrote Juno Berthelsen, a co-founder of the Greenlandic organization Nalik, in a widely shared social media post in 2020.

“The reason is simple,” said Berthelsen, who is a candidate in next week’s parliamentary election for the Naleraq party. “These statues symbolize colonial violence and stand as an insult and an institutionalized daily slap-in-the face of people who have suffered and still suffer from the consequences of colonial violence and legacies.”

Greenland is now a semi-autonomous territory of Denmark, and Greenlanders are increasingly in favor of getting full independence — a crucial issue in the election on March 11.

Some say Greenland’s independence movement has received a boost after Trump pushed their Arctic homeland into the spotlight by threatening to take it over.

At a time of uncertainty, “it’s important for us to have faith,” said the Rev. John Johansen after a service at the Hans Egede Church, where an American couple visiting Greenland attended wearing pins that read: “I didn’t vote for him.”

Greenlanders “always have faith, no matter what,” Johansen said. “Of course they worry about Trump because they can lose their independence, their freedom. They don’t want to be American; they don’t want to be Danes. They only wish for their own independence.”

The Church of Greenland separated from Denmark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in 2009 and is funded by Greenland’s government. Although the Lutheran Church comes from Denmark, the leader of the church in Greenland is proud that it remains uniquely Greenlandic.

“It was translated often from Danish rituals, but since the beginning we have always used our language and it goes directly to our heart,” Siegstad Munk said. “When I see other Indigenous people, most go to their church in the state’s language. But here in Greenland, everything goes from Greenlandic. It’s good for us to have our own religious language.”

In recent years, young people have increasingly demanded the revival of pre-Christian shamanistic traditions like drum dancing; some have been getting Inuit tattoos to proudly reclaim their ancestral roots. For some, it’s a way to publicly and permanently reject the legacy of Danish colonialism and European influence.

Still, the Lutheran Church, Nielsen said, remains for many an important part of the national identity.

“People wear the national costumes when children are present or at funerals and weddings and the religious holidays,” he said.

Greenland was a colony under Denmark’s crown until 1953, when it became a province in the Scandinavian country. In 1979, the island was granted home rule, and 30 years later Greenland became a self-governing entity. But Denmark retains control over foreign and defense affairs.

Until 1953, no other denominations were allowed to register and work in Greenland other than the Lutheran Church, said Gimmi Olsen, an assistant professor in the theology department at the University of Greenland.

Since then, Pentecostal and Catholic churches — mostly serving immigrants from the Philippines — have settled in Greenland. Other Christians include Baptists and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

As in other parts of the world, younger people tend to go to church less, and more are joining the ranks of the religiously unaffiliated — even when, at least on paper, they remain part of the Greenlandic Lutheran Church.

“People are not always ‘belonging’ to the church, in the sense, that they do not go there every Sunday,” said Olsen.

“For the vast majority of the Greenlandic Society, being a member of the Lutheran Folk-Church is the normal,” he said, even if it is normal to only go to church a few times a year, for baptisms, weddings, funerals, or on Christmas and Easter.

That kind of solemnity and joy coexist through ritual and tradition. On the same day, even in the same service, there can be contrasting emotions.

In Nuuk, a pastor dressed in black robes and white ruff collar faces the altar with the rest of the congregation to somberly speak to God. In nearly full wooden pews, congregants follow the service in silence.

But then, the quiet, prayerful service goes from what seems like a black-and-white silent film to a technicolor talkie. Pastor and congregants will sing hymns and beam with a smile and cheer on the couple about to get married, or the baby about to be christened. The men are in white anoraks and women in the traditional national dress of shawls stitched with colorful beads and boots made of sealskin reserved for formal occasions.

“I’m not worried about the church,” said the Rev. Aviaja Rohmann Hansen, a pastor of the Hans Egede Church.

“If we saw few people like in Denmark, I’d be worried. But we have people at the church every Sunday. We have a lot of baptisms, we have a lot of confirmations, we have a lot of marriages. So, I’m not worried about the church. I hope this will continue because it makes Greenlanders come together.”

On a recent day, she baptized Marie Louise Nissen’s grandson at the Nuuk Cathedral.

“Baptism is important,” Nissen said, smiling as she was briefly interrupted when one of her young family members had to be rescued from slippery ice outside the church.

“It’s important to us to invite the kids into the Christian faith,” she said. “This is a good day to celebrate and give a name — that’s what is important to us.”

Her daughter, Malou Nissen, then chimed in: “I think it’s more a tradition thing for me. It’s a day you’ll remember forever.” When asked what the Lutheran Church means to her, she said: “Everybody is welcome. It’s a place for tears and for happiness.”

Her mother agreed: “Today is a celebration; maybe next month it’s a funeral, and it’s the same place we go — it’s the same place to make memories.”

___

Associated Press journalist Emilio Morenatti contributed to this report.

__

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.