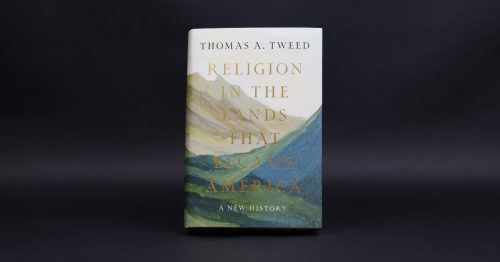

RELIGION IN THE LANDS THAT BECAME AMERICA: A New History. By Thomas A. Tweed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2025. Xiv + 620 pages.

There are different ways of telling the history of religion. One can do so narrowly or broadly. Regarding the history of religion in the United States or North America, one could focus on a particular religion, such as Christianity. Many of the leading historians of American religion have taken this route. When I studied American Church History in seminary, we used Sydney Ahlstrom’s A Religious History of the American People. When I taught that same class, I used Mark Noll’s A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada. Both of these books, which are excellent, focused on the history of Christianity. What if, however, one takes a much broader view, and starts not with the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, but with the first people who inhabited the lands that became America? That would be a very different story. It isn’t that one is wrong and another is correct, but they are different. In this moment in history, when we are witnessing backlash against “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” together with attempts at teaching so-called “patriotic history” (what I would call propaganda), we need to see the bigger picture.

Robert D. Cornwall

We are fortunate that Thomas A. Tweed has written a macro history of religion in America. Tweed’s book is titled: Religion in the Lands that Became America: A New History. Tweed is the Harold and Martha Welch Professor of American Studies and professor of history at the University of Notre Dame. While he acknowledges the important work done by Ahlstrom and others, Tweed sets out on a different journey. Rather than starting with the Pilgrim landing at Plymouth Rock, Tweed tells “a new story that includes more characters and more places. He writes that while we will “meet familiar figures like Bradford and those transatlantic migrants gathered around New England’s ‘hearths and altars’” but we’ll also meet many other characters, whose stories have not been told, starting with “Horn Shelter Man, a medicine man buried in with 100 grave gifts in a rock shelter in Texas about 11,000 years ago,” among others (p. xiii).

Tweed takes us on a journey from Horn Shelter Man’s burial site in Texas, some 11,000 years ago, to the place of religion in present-day America. He moves the story forward according to several turning points that are mostly technologically oriented, such as moving from foraging to farming, and onward to the contemporary age of fiber optics. As we journey through time, we encounter numerous stories relating to religious practices and beliefs that are generally not told by focusing on people and groups living on the margins of the dominant society. With that in mind, Tweed devotes considerable space to recounting the stories of the religious life of Native Americans, including how they made accommodations to the dominant religions and how many sought to reclaim their stories and beliefs. He also shares the stories of the people who came to the American shores as slaves, most especially from Africa, some of whom were Christians. We also encounter stories of the religious life and beliefs of other immigrant communities, especially those who came from Asia.

While important Tweed weaves into the larger story important Christian figures, he wants to make sure that the many stories that were neglected in other works, including Ahlstrom’s book, are given proper attention. Because Tweed tells the broad history of religion in the lands that became America, beginning with the earliest migrations, less attention is given to the stories most often told. If you want an in-depth history of the role of Puritanism or revivalism in American Christian history, you will want to look elsewhere. However, if you wish to view the rest of the story, you will find Tweed’s history very helpful. This is especially true at a time when political forces at work in the country are seeking to push these stories further to the margins. Telling this larger story is making many white Americans (those of European descent) uncomfortable. So, in pursuit of removing diversity, equity, and inclusion programs from the government, educational institutions, and even corporations, uncomfortable stories are being removed. Whether intended or not, Tweed’s history is a helpful and needed response.

The title of the book is an important clue to the way Tweed organizes his history. That he uses the title Religion in the Lands that Became America as a reminder that “America” didn’t exist until after the European migrations. This serves as a reminder that the “Americas” were not uninhabited before the European migrations, and thus, to get a full picture of religion in these lands, we must recognize the histories, customs, and religions of the people who lived here before the arrival of Europeans.

Even as the nation debates the value of immigration to the “American” reality, migration plays an important role in this story, beginning with the first migrations from Asia, perhaps as early as twenty thousand years ago, and perhaps elsewhere. The story Tweed tells about the different migration theories that have developed in recent years is intriguing. But wherever the people who have resided on this continent came from, migration plays a central role in the story. This is true whether migration was due to “spiritual motives” or climate, conflict, or enslavement. Whatever the case, people sought a home for themselves. As such, Tweed seeks to show “how communities used utilitarian technologies and figurative tools to make, break, and sometimes restore eco-cultural niches.” With that in mind, Tweed focuses on four eco-cultural transitions, beginning with foraging, before moving to farming, factories, and then fiber-optics. Tweed begins his story with the shaman who was buried in Horn Shelter some 11,000 years ago. The Horn Shelter man embodies evidence of the existence of early hunter-gather cultures and their religious practices in the Americas. From there, we move to agriculture, which existed in the Americas long before European migration. Then, moving into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we see the age of factories and industrialization. Finally, in the story of religious life in the age of fiber optics, which is the current age. It is interesting that Tweed used technological changes to organize his study, but it makes great sense, as readers will discover.

Tweed’s Religion in the Lands that Became America comprises ten chapters. The first section is designated as Foraging,” and it has one chapter. In the chapter titled “Foraging Religion: Ancient Crossings and Mobile Niches, 9200-1100 BCE,” offers his interpretation of the various migrations and entry points that took place from at least the time of the Horn Shelter man, to the first evidence of agriculture in the Americas, noting that the evidence of human presence in the American continents goes back, perhaps thousands of years earlier than previously thought. But during these earlier millennia, the peoples were largely hunter-gatherers, who developed religious practices, often represented by burial sites, that reflect that particular form of life.

Part Two is the longest portion of the book, comprising five chapters. Tweed uses the technological concept of “Farming” to organize this section. Interestingly, although European settlers, including Christian clergy and missions, wanted to civilize native populations by teaching them to farm, many native peoples had been engaged in farming for millennia. It is just that they had different ways of farming. With that in mind, Tweed uses Chapter 2, which is titled “Farming Religion: Sedentary Villages and the First Sustainability Crisis, 1100 BCE-1492,” to tell the stories of several of these farming civilizations, including the Cahokia peoples of the Mississippi Valley as well as the Chaco peoples of the Southwest, along with their descendants.

In Chapter 3, titled “Imperial Religion: Agricultural Metaphors, Catholic Missions, and the Second Sustainability Crisis, 1565-1756,” we move to the earliest European conquests in the Americas. With this conquest, another sustainability crisis erupts. This chapter reminds us that the British migrations followed after the Spanish ones, with each of these migrations bringing their own dynamics to the lands we call America. The period under discussion largely covers the period of Spanish presence in the region, including in Mexico and lands further south.

Chapter 4 covers a similar period but focuses on French and primarily British experiences from the first British colonies to the Seven Years War (French and Indian War). Tweed titles this chapter “Plantation Religion: The Meetinghouse, the Multi-steeple City, and the British Slave Plantation, 1607-1756.” Tweed introduces us to the British — and to a lesser extent, the French — migrations, conquests, and planting of European religion. In the British colonies, which were primarily Protestant, with pockets such as Maryland where Catholics found refuge, we see how the British planted their civilization and religious identities in the region. This story ends in 1756, with the Seven Years War (note that Tweed uses this term rather than the French and Indian War). It is important to remember that the Seven Years War took place on both the European and North American continents and was in many ways the last of the wars of religion that broke out after the Reformation.

Chapter 5 begins in 1756 and runs to 1791 and is titled “Rebellious Religion: Tyranny, Liberty, and the ‘Pursuit of Happiness.'” Here, the focus is on the move toward the Revolutionary War and the birth of the United States as an independent nation. Here, Tweed helps understand the religious complexity that emerged as the new states sought to address the religious differences present in the new nation. We see both attempts to provide religious liberty and the emergence of civil religion. Before moving to the final chapter in this section, I need to note that throughout the chapters that begin with the Spanish presence in the Americas through the British migrations and the birth of the United States as a nation, Tweed continually brings the stories of the Native population into the conversation, noting their interactions, usually tragic, with European colonists, as well as the importation of slaves from Africa, including their contributions to the emerging American context. For them, the promise of liberty was far off.

The final chapter in this section is titled “Expansionist Religion: Expanding and Contracting Worlds in the Agrarian ‘Empire of Liberty,’ 1792-1848.” This chapter reminds us that in the early years of the United States, the nation was still largely agrarian. That was especially true in the South, where slaves worked on the plantations. It is in this section that we encounter some of the key contributors to Early American religious life, such as Richard McNemar and Charles Finney, along with political figures such as Thomas Jefferson. While many early leaders were Protestant, Tweed also emphasizes the role of Roman Catholics in the expanding nation. This chapter begins by exploring the attempt to find solutions to the church-state relationships, along with the movement west as the nation expanded, usually at the expense of Native populations who continually found themselves pushed off their lands, often through government efforts. Of the enslaved, Tweed writes that they used “religion to assert dignity and nurture hope” (p. 210).

The third section is titled “Factories.” There is some overlap with the previous section, as Chapter 7 begins with the pre-Civil War effort and continues into the twentieth century. This chapter, which opens the section, is titled “Industrial Religion: The Sharecropper South, the Reservation West, and the Sustainability Crisis in the Urban Industrial North, 1848-1920.” We start in the antebellum world and move through the Civil War, to the end of World War I. The subtitle reveals Tweed’s focus, since the sharecroppers were largely African Americans who sought to make a life after emancipation, often limited to farming lands owned by the former plantation owners. As for the reservations in the West, they were the places to which Native Americans were removed. Again, we see how religion played a role in giving hope but sustaining resistance as well. Then there is the industrialization of the northern cities, which led to considerable movement from the farms of rural America to the cities, where factories offered jobs and the promise of new opportunities to flourish. This is also the era of increased immigration, which led to struggles to integrate new residents of the nation, along with their religions and cultures. This is also the era of American imperialism, as the United States fought the Spanish, annexing their territories in the Caribbean and the Philippines. It is also the period in which places in the Pacific, including Hawaii, were added to the mix.

The second chapter in this section (Chapter 8) is titled “Reassuring Religions: Shifting Fears, Diverging Hopes, and Accelerating Crisis.” This chapter focuses on the period 1923 to 1963, during which the nation experienced a period of prosperity, followed by the Great Depression, another World War, the post-war expansions of American power, the Cold War, and the beginnings of the civil rights movement. That leads to the final chapter in the section, which covers the period 1964 to 1974. On a personal note, these were the years I grew up in, graduating from high school in 1976. Chapter 9 is titled “Countercultural Religion: Spiritual Protests, Postponed Reckonings, and ‘Deep Division.'” This is the era of the full bloom of the civil rights movement, the Great Society, the Vietnam War, with accompanying protests, hippies, environmentalism (Earth Day), the Nixon backlash, and Watergate. It was also a period of increasing disillusionment with the religious establishment, which began the decline of the Protestant mainline.

The final Section of Tweed’s history is titled “Fiber Optics.” The section’s one chapter (Chapter 10), which covers my adult life along with most readers of this review, is titled “Postindustrial Religion: Networked Niches, Segmented Subcultures, and Persistent Problems, 1975-2020.” Here, Tweed tells the story that runs from the mid-1970s, as the United States emerged from Watergate and Vietnam, to the end of the first Trump administration. As Tweed points out, this is an era of “America’s religious restructuring.” This is the era of megachurches and online religion, along with the continuing decline of institutional religion. While he ends the story in 2000, with the emergent problems of the first Trump administration, the realities of this era continue to this day.

Throughout Thomas Tweed’s Religion in the Lands that became America, we are reminded that change is constant, and that affects different peoples and groups in different ways. We’re reminded that too often we neglect the stories of the people who are marginalized (a word that is currently out of fashion). However, these stories need to be told if we are to fully understand the religious makeup of these lands, even if what we discover makes some folks uncomfortable. Part of this conversation is the reminder that these lands were inhabited long before the European migration began. It is good to remember that these people had their own civilizations and religious beliefs and practices that helped them make sense of their world. The same is true for those who migrated, even when not of their own choice, as with enslaved Africans, who brought with them their own religious life and practices. We should not forget that at least some of the enslaved were Muslims and Christians.

In his book Religion in the Lands that Became America: A New History, Thomas Tweed has given us a unique and helpful account of the religious life of the peoples who have lived in these lands. It is a broad history that is well documented (there are more than two hundred pages of endnotes). While there is a place for the well-regarded histories by scholars such as Mark Noll and Sydney Ahlstrom, they don’t tell the whole story, nor does Thomas Tweed. However, Tweed does broaden the conversation in important ways. For this, we can be grateful, especially at this moment in a time when efforts are underway to tell a much narrower story.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books, including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found here.