Charismatic leaders have made waves in American politics in recent years, particularly with the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States. Observers have noted how Trump captured the imaginations of his audience and was able to sell them compelling (and false) narratives about the 2020 election being stolen from him. American politicians on the left, such as Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have also captured the imaginations of their followers by telling stories about how the economic elite are exploiting the 99% of Americans. All of these charismatic leaders have persuaded people to follow them by telling compelling stories in which their followers can see themselves — stories that make them feel important.

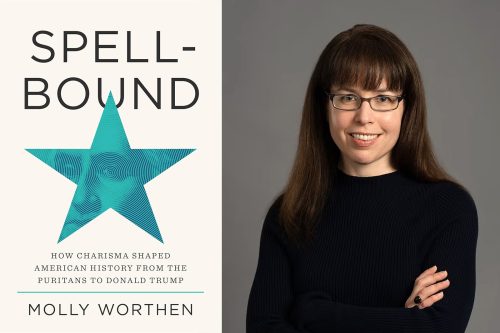

In the United States, there is a long history of charismatic leaders capturing the imaginations of their audiences and spurring them to action. In her book Spellbound: How Charisma Shaped American History from the Puritans to Donald Trump, associate professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Molly Worthen traces charisma in America from pre-colonial times to the present, examining how cultural perceptions of charisma have evolved. Worthen includes a wide range of historical figures in her book, including Anne Hutchinson, Andrew Jackson, Angela Davis, Martin Luther King Jr., and Donald Trump.

Kenneth E. Frantz recently spoke with Worthen for Word&Way, and the following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How do you define charisma, and why do you consider it important to write about?

This was a major reason why I embarked on this project. It seemed to me that in everyday conversation, charisma is often this word that we punt to when we are observing some dynamic between a leader and followers that we can’t quite crack. And I guess that intrigued me, and in retrospect, I also think I was confused at the start of this project. I confused charisma with charm, and I think they’re related but distinct phenomena. Charm is I think a specific personal trait that’s possessed by those kinds of people who are really good at working the room at a cocktail party, who make you feel like you are the center of the universe and your problems are their problems. And I thought going into this project that I would be writing about a lot of really charming people, people who are really good at working the room, great public speakers, really good looking.

And that turned out to be really the minority of my subjects. Many of my subjects provoked the mark of charisma. It emerged was the provoking of a very polarizing response — at least as many, if not more, people find charismatic figures repellent as find them attractive. Piecing together the evidence over the span of centuries, I found myself concluding that the heart of charisma as it manifests in the creation of mass movements is a leader’s ability to tell a particular kind of story, to invite potential followers into a new narrative that is better than the narratives currently on offer in the culture and connects their individual puny story of suffering and struggle to a big story of transcendent meaning and also is premised on a new view of reality. Often, charismatic leaders pull back the veil on a whole set of perceptions that had eluded people before. And so that to me is the through line. And I weave it together in the book with charisma in the New Testament sense, in the sense that Paul uses it and the narrow meaning that it had for 1900 years until Max Weber borrowed it from biblical studies and church history and funneled it into the way we speak about politics. But I think that the two kinds of charisma, while distinct, are very much part of one story.

You mentioned in the book that charismatic leaders can be confusing to outsiders. So I’m thinking in terms of Donald Trump, but also Elon Musk and AOC, who exude a certain kind of charisma, but outsiders often don’t understand it. So would you mind elaborating on that point?

Maybe one of the most striking early examples was Joseph Smith. And I was going through some of the early accounts of encounters with him, and certainly you can find accounts from early converts to the Mormon faith who talk about how personally magnetic he was. And one woman says she shakes his hand and immediately feels the Holy Spirit thrilling from the top of her head to the soles of her feet. But then you can find skeptics, plenty of skeptics who met him and had the opposite reaction — thought he was kind of a clown, he had these sort of weird fat hands, they didn’t want to shake his hand. And of course, so many of the first generation of Mormon converts, I’m thinking especially of the thousands of converts in the British Isles, accept the Mormon gospel and make the decision to uproot their lives and move across the Atlantic to Nauvoo, Illinois, right this tiny nowheresville town on the banks of the Mississippi without ever having met this prophet on the strength of the story, the story about him, the story about the golden plates.

I think that the heart of that polarized reaction that you are pointing to that continues to manifest up into our own time has to do with the characteristics of a compelling story. A gripping story casts some people as heroes. And I mean that makes you want to become a follower if the story is inviting you into an attractive role, but it also casts other people as villains or just ignores them, writes them out entirely. A person’s relationship to the story that a charismatic leader is telling is highly determinative of their response to that leader’s whole campaign, but also their response to that leader interpersonally. I’m thinking of famous examples like Bill Clinton. People often talk about Bill Clinton as just incredibly charismatic, and he would make you feel like you’re the only person in the room at a fundraiser or if you’re sitting in a room hearing him give a speech. But I would wager that you’re only in that room to begin with because you have already bought into the story he’s telling. And in fact, if we remember, and this remains true, Bill Clinton has always been a deeply polarizing figure as many Americans found him to be dishonest and sleazy as exciting.

In the book, you go from the Puritans to talking about academics like Marcuse and Angela Davis to the Pentecostals and charismatics to Donald Trump. That’s kind of a wide range of case studies. So would you mind talking about why you chose particular case studies and why you left others out?

I’m a typical historian in that I think immediate context is really important. And as I was trying to make sense of the broad sweep of American history since European contact, it began to seem to me that the story broke into five broad chapters in which a particular charismatic style emerged as especially culturally resonant, because leaders who told a particular kind of story were responding to the anxieties and desires and circumstances of that period. That’s part of the answer to your question, that these are periods of history in which the broad social and cultural circumstances are so different. So that helps account for why very different figures rise to the top. In particular, I was struck by a kind of action and reaction that I began noticing across the span of history that, in some ways, most of the time charismatic leaders are always defining themselves and telling a story in response to a kind of critical distance from established institutions and traditions.

And I think this is a point that Max Weber made that remains useful, that charismatic authority is distinct, although it can be combined with, but it’s distinct from authority premised on institutions or traditions. But I think there have been times in American history when the impulse to tear down those institutions has been especially strong, and those have been followed by periods when there’s more of an appetite for positive building — whether that manifests in military conquest or simply a tendency to trust representatives of institutions, as was true after World War II. So that too is part of that story of action and reaction helps us understand the wide range of charismatic leadership that has figured in American history.

You mentioned that each era of American history has its own type of charismatic leader that defines it. Would you mind discussing the different types and how you went about defining and discerning those?

The five types are the prophets, the conquerors, the agitators, the experts, and the gurus. The prophets are the key type for the era at the beginning of the early 17th century. And really, this is still really the aftermath of the Reformation and the aftermath of the crackup of Christendom. So I wouldn’t want to suggest that prior to the Reformation, everything was smooth sailing. There’s no descent at all. There’s plenty of mystics and dissenters of various types running around medieval Europe, but the Catholic church up until the Reformation — generalizing here, but I think it’s useful — had fairly effective ways of channeling those claims, those attempts to do a kind of end run around the hierarchy and something important shifts in the Reformation and its aftermath. And while think that the magisterial reformers, people like Martin Luther and John Calvin, I mean in many ways they loved institutions, they wanted strong institutions.

They were horrified by some of the radical extremes to which their followers and successors took some of their ideas. There is in that central Reformation insight that we associate most closely with Martin Luther, this idea of personal justification before God and the priesthood of all believers, there is this highly unstable, radical seed that really flourishes in the context of the American colonies. So the prophets are those charismatic leaders who are, in a sense, standing closest to medieval Christendom and operating at a time when the structures and ideas of old-world Christendom still have a tremendous amount of purchase in shaping the world of the people they’re trying to reach. The prophets are also a category for whom New Testament charisma in the Pauline sense and charisma in that more kind of Weberian sense are totally inseparable.

The prophets are the bridge from the old world to the new. The era of the conquerors is the era of the early republic and kind of the first half to two-thirds of the 19th century. I mean conquerors in both the physical military sense, right about Andrew Jackson and Napoleon. Of course, Napoleon is not an American figure, but his shadow looms so large over the whole Western world and shapes how Americans think about military leaders for that period. But I also mean conquest in the spiritual sense. Someone like Joseph Smith combined the two very much had a vision of a kind of spiritual manifest destiny in his vision for what the Mormons would accomplish in the West and in the conversion and assimilation of indigenous Americans.

And I think the appeal of all those forms of conquest and that kind of story of what America is, what it means to be a person of scientific curiosity and progress, that’s all one story. The period of the conquerors is followed by the turn of the 19th into the 20th century by this period I call the agitators. And they echo the prophets in many ways. They are more anti-institutional figures. They’re responding to the growth of, simply the scale and the interwoven nature of, the late 19th-century American economy — the growth of the federal government and its presence in people’s lives after the Civil War. And so there is this prominent populist strain, certainly in the political manifestations of this, but this is also this really interesting period in New Testament charisma, which I’m trying to trace as well. And so this is the period when holiness Christianity gives birth to Pentecostalism. And in many ways I read the birth of modern Pentecostalism as a reaction to modernity and an expression of frustration with the stultification of church institutions and the failure of a more rationalistic modern approach to Christianity and spirituality to really deliver on its promises, and this abiding hunger that people have for a direct connection to the divine.

Hitler becomes just the overriding shadow across what charisma means for people in the West, both at the popular level and scholars who are trying to make sense of the world order after this. And so many of them conclude that charismatic leadership leads to this kind of genocidal demagoguery, and it is incompatible with democracy. It’s something we have to transcend. And so there arises this exceptional period in American history because Americans generally have a robust history of skepticism of expertise and technocrats.

But the 20-odd years after World War II are this exception to that because there’s a sense in which we never, again, we have to lean as far away from charismatic unpredictability as possible. Let’s trust the experts in their story of progress and that charismatic style of authoritarian leadership, that’s not something we do anymore. And you have all these social scientists looking to the global south and seeing examples of it in the newly independent African states in this way that is really quite blind to the persistence of those same dynamics in their own culture. There’s a way in which the experts sow the seeds of their own demise in some sense, I think. I mean that institutionally failing on many of their most ambitious promises and becoming associated with these magnificent failures, particularly the Vietnam War. In the context of academia though, and this is where Herbert Marcuse and Angela Davis come in, there is this sort of way in which this class of anti-institutional children of the institutions eat away at the authority of universities from within.

And I think that’s a big part of their decline in the eyes of the American public. And so, as we all know from the poll data from about 1960 forward, it’s generally a story of declining trust of Americans in all institutions, churches, the Supreme Court, Congress, mainstream media, universities. And to me, that’s what secularization is. And the declining authority of religious organizations — that’s one piece of this broader shift and this way in which we are now in this era, I call the era of the gurus, in which Americans are totally atomized. We have generally very low levels of loyalty and affiliation with any kind of communal institutional activity. And I think that’s left us vulnerable to a more destructive kind of charismatic leader. So to me, the guru category of leader follows many of the same patterns that you see in the era of the prophets and in the era of the agitators. But in those periods where destruction was more in vogue, I think there was kind of a healthier social political ecosystem that made it possible for Americans to better evaluate the pitch. The stories that charismatic leaders were telling them, there were countervailing sources that kind of ballast in traditions and in communities they were associated with, certainly in the middle of the 20th century, more robust mainstream media establishment. And that’s all really eroded. So to me, this is a story of continuity, but also there are features of our own era that are pretty unique.

In your prior book, Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, you do touch on the heart and mind dynamic within evangelicalism and how charismatic leaders have tapped into that. Do you see a connection between Spellbound and Apostles of Reason?

I guess I’m always interested in questions of intellectual authority and why people trust certain elites to describe the world and not trust others. And so in that sense, both books are about authority. I think that in Apostles of Reason, as in Spellbound, I am telling a post-Reformation story, and I’m giving an account of a situation that’s kind of particular to America and maybe especially exacerbated in evangelical Protestantism because evangelical Protestantism is a culture of fairly weak institutions. And this is part of both the evangelistic genius and energy of evangelical Protestantism. It’s so easy to be a religious entrepreneur and just hang up your own shingle and start your own church. However, it does create an unstable subculture that is, perhaps compared to some other subcultures, more vulnerable to the appeals of charismatic leaders who are not necessarily counterbalanced by checks and balances.

I don’t think that charisma in and of itself has a particular moral valence. It can manifest in very heroic episodes in our country’s history. And I write about Martin Luther King, I think he would be an example of someone whose charismatic story that he’s offering followers casts the world in a revelatory light. It reveals true features of the world. And that is the difference between a charismatic leader who is working for the moral good and one who manipulates. A leader who presents a story based on claims that are not connected to objective facts is one who, I think, is much more likely to lead people into something that amounts to a kind of conspiracy theory story of the world. But charisma in and of itself is morally neutral. I do think, though, you’re right to draw a connection and that there is this way in which evangelicalism is particularly fertile ground for some of the dynamics that I am describing.

It’s fertile ground for authority figures like a Donald Trump or a Mark Driscoll to come in and tap into the energy.

I think so. I do, though, I want to caution, on the one hand, I think the lens of charisma is really useful for understanding a certain very important subset of Donald Trump’s base. But so many Trump supporters that I talk to or who I read are, I would not say they are kind of captivated by him in a charismatic sense. I would say they are supporting him for more typical prosaic reasons of political calculation that have to do with his policy positions. And so there’s a danger in applying the lens of charisma, especially to the other side from yourself, in that it’s kind of letting you off the hook and giving you an excuse to dismiss that leader’s followers as irrational. And I think that’s a mistake. Just because a leader is telling a story doesn’t mean that that story is irrational, right? A story is one way of organizing information, and it may or may not be accurate, but it shouldn’t be an excuse to dismiss a movement and not look more deeply into the appeal they see.

Would you say the left should not let themselves off the hook and follow charismatic leaders or let charisma sway them, so to speak?

Well, I think people on the left need to, unless they have reason to do otherwise, they should take Trump supporters at their word when they lay out in a straightforward manner the vision of social conservatism that they see, regardless of Trump’s personal proclivities.

They see as one that they can only support by voting for the Republican candidate, and that they should take seriously the rise of Trump as an indictment of institutions and the colossal failure by institutions including the mainstream parties, but also the institutions that have basically been captured by the left, especially universities, to win and hold onto the confidence of the American people. I think that the Democrats have a real charisma problem right now. They have a reasonable bench of younger leaders who are wonderful orators and very charming, effective communicators, but I’m not sure that they have figured out the grand story that they can offer. That is the counter-narrative.

Kenneth E. Frantz is a freelance writer and a doctoral student in sociology at the University of Oklahoma. You can find more on his website and follow him on Bluesky @kennethefrantz.bsky.social.