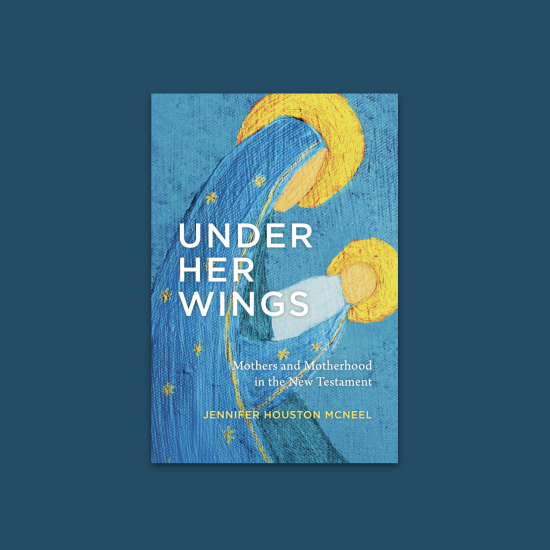

HOW DID THEY READ THE PROPHETS? Early Jewish and Christian Interpretations. By Michael B. Shepherd. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2025. Xiii +162 pages.

For Jews, Christians, and Muslims, the prophets of what Christians call the Old Testament speak loudly. Preachers, like me, often turn to them to address contemporary concerns and crises. Although the prophets addressed issues contemporary to them, their messages often speak to our own concerns. This is especially true of books such as Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos, and Micah. The prophets call our attention to the way God sees things, while pointing out pathways that lead to justice and mercy. From them, we learn how to walk with God. The prophets themselves draw upon Torah, interpreting it so that the hearers and readers might know the ways of God. This reminds us how biblical authors will interpret the words of other biblical authors, such that Scripture interprets Scripture. We know that this is especially true of the authors of the New Testament, who regularly draw from earlier texts to communicate their messages. Jesus himself is portrayed in the Gospels as drawing on Torah and the prophets for inspiration and authoritative teaching. As such, he drew on these texts and reinterpreted them to speak to his own context. That shouldn’t surprise us since Jesus, as a Jewish teacher, would have known what became scripture.

Robert D. Cornwall

The question that Michael B. Shepherd asks as the title of the book under review reveals is How Did They Read the Prophets? The book’s subtitle clarifies to an extent who “they” are: Early Jewish and Christian Interpretations. I will show in due course who Shepherd understands “they” to be.

Michael B. Shepherd, the author of this book, is a professor of biblical studies at Cedarville University. Before moving to Cedarville University, he taught biblical studies at Louisiana College in Pineville, Louisiana, having earned his Ph.D. at Southeastern Baptist Seminary.

In this book, what Shepherd means by early Jewish and Christian interpretations focuses largely on interpretations found within the biblical canon, whether Jewish or Christian. In addition, he makes use of Jewish targums and midrash. Thus, when it comes to early Christian interpretations, he largely limits himself to the New Testament. Thus, he does not engage with the biblical interpretations of figures such as Irenaeus, Origen, or Jerome. As I read the subtitle of the book, I did expect to find him engaging with interpreters from the early centuries of Christian history. However, that is not his focus.

As for the methodology used here, Shepherd draws on the method used by James Kugel, professor emeritus in the Bible department at Bar Ilan University in Israel and the Harry M. Starr Professor Emeritus of Classical and Modern Hebrew Literature at Harvard University, in his Grawemeyer Award-winning book The Bible as It Was (Belknap Press, 2017), which focused on the portrayal of Moses as a prophet in the Pentateuch (Torah). In this particular book, Shepherd focuses on the Latter Prophets—Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jeremiah, and the Twelve (Minor Prophets). He shares with his readers that his purpose here is to let the “ancient interpreters collectively to give a guided tour of the textual details of the composition in its given form and sequence.” In other words, Shepherd is not offering the reader a general introduction to these books. That is something one will find elsewhere. Instead, he is interested in how the prophets were interpreted by biblical authors as well as select Jewish interpreters. Thus, Shepherd focuses his attention on the way other biblical writers and Jewish writers engaged with the text of the prophetic writers.

When it comes to textual elements, Shepherd brings into the conversation the various forms the texts of the prophetic writings take. This includes the Masoretic Text of the Old Testament, on which our modern translations largely rely, along with the Old Greek and Septuagint (Greek) translations. He suggests something that was new to me, which is that it appears the Old Greek translation relies on Hebrew Texts that predate the Masoretic Text. In revealing this possibility, we can see how interpretations emerge over time. It also reminds us that we may value the Hebrew text; there are likely Hebrew texts that not only predate the primary Hebrew text of the Old Testament but that Greek translations might offer us a look at earlier possible interpretations.

Michael B. Shepherd’s How Did They Read the Prophets? is accessible to readers who have some knowledge of the biblical text, though general readers may not know about the Jewish targums and midrash. However, Shepherd offers chapters discussing Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and then the Twelve, together with a final chapter on “The Prophets as Exegetes.” As he reminds the readers, if they are looking for an introduction to these books, they should look elsewhere. On the other hand, though Shepherd appears to take a more conservative view of the books (I’m not sure whether he considers Isaiah to be one book or two), he does help us better understand how biblical texts interpret and build upon each other. Of course, the New Testament writers engaged not only with biblical texts but also with earlier interpretations that lay outside what we know to be canonical. We also know that the New Testament writers depended on the Greek translations, whether Old Greek or the Septuagint, which offer their own interpretations.

I do want to take note of the final chapter on “Prophets as Exegetes.” More specifically, Shepherd’s comments about the role that scribes played as exegetes. He notes that the “older conception of a scribe as a mere copyist has given way to a newer, more accurate view of scribes as exegets and composers. The older view of prophets as preachers of oral messages has been complemented by an awareness that the concept of a prophet developed in such a way that the scribe became a new prophet” (p. 114). Thus, the prophets themselves serve as interpreters of other biblical texts. Shepherd’s book, How Did They Read the Prophets? offers us a helpful introduction to how biblical writers and biblically adjacent writers interpreted each other.

As I noted above, when it comes to Shepherd’s understanding of Isaiah, at some points he brings a more conservative view of inspiration than some, including me, might take. Readers who come to this conversation from a different vantage point will want to keep that in mind. Nevertheless, Shepherd’s assumptions regarding inspiration and the perfection of scripture, while present, do not seem to overwhelm his own interpretations. In other words, if one understands where the author is coming from, then one can find insight into the texts that are helpful, so one can better interpret Scripture as well as understand where interpretations come from. As a reader, while one might expect, based on the subtitle, that Shepherd would extend his discussion of early Christian interpreters to include interpreters other than the New Testament writers, nevertheless, Shepherd sufficiently explains the boundaries that one understands why the choice was made. Therefore, I do believe that Shepherd’s How Did They Read the Prophets? has significant value, especially for clergy.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books, including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found here.