NOTE: This piece was originally published at our Substack newsletter A Public Witness.

New York City. Washington, D.C. Hollywood.

These are places of enormous cultural influence. They shape the way we understand ourselves as a society while establishing the trends and expectations that determine how many of us act in the world. These cities wield tremendous power and have extensive reach over how millions, perhaps even billions, of people go about their lives.

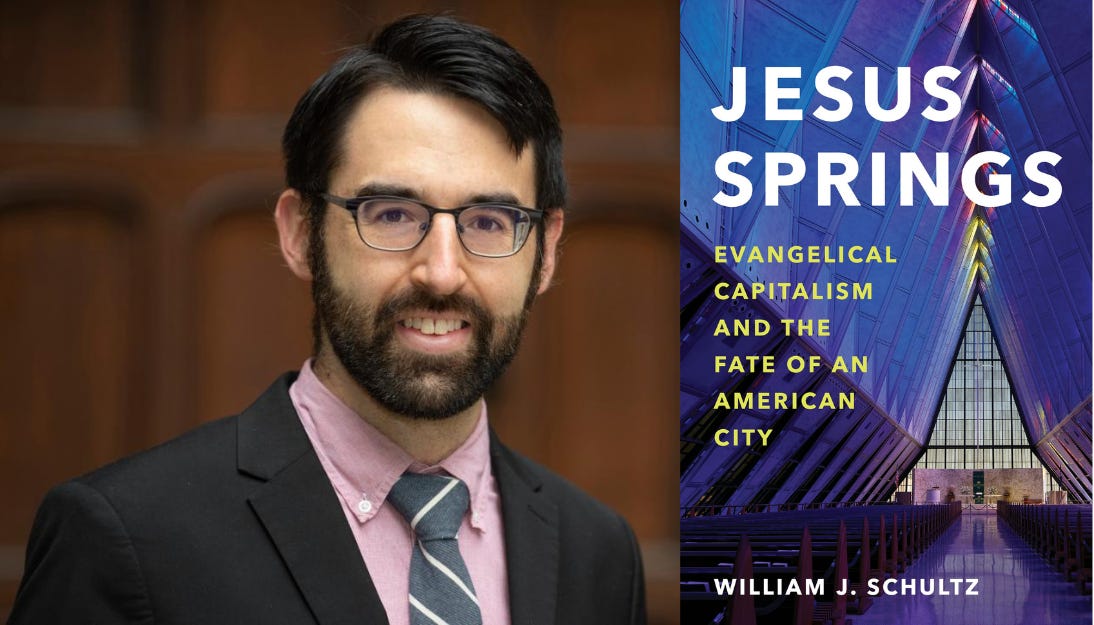

In Jesus Springs: Evangelical Capitalism and the Fate of an American City, William Schultz, a historian of American religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School, makes a compelling argument that there was a moment where Colorado Springs — yes, Colorado Springs — warranted similar recognition. It’s a city where religious and military authority were concentrated and mixed in ways that led to profound social change.

Colorado Springs’ rise to significance was an accident of history. Schultz explains how changes in military spending, the availability of cheap land and low-wage labor, the entrepreneurial spirit of key individuals, and a network of Christian leaders and organizations led to the rise of a conservative mecca where national identity and religious zeal became intertwined. If Christian Nationalism had a capital city, Colorado Springs would be it.

Through its focus on one particular place, Jesus Springs narrates the rise and evolution of evangelicalism in the United States. Many people know the broad contours of that story already, but few grasp the drivers of its development, the nuances of its subplots, or the contingencies that might have led to different endings. By telling that tale through an in-depth look at what has unfolded in one city, the book makes those subtleties easier to comprehend and the plot more entertaining.

“The early Cold War was the pivotal moment in the emergence of modern American evangelicalism,” Shultz writes. “Between the 1930s and 1950s, a rising generation of conservative Protestants undertook a sustained effort to ‘Christianize’ the United States, carrying forward an impulse that had motivated many American Protestants throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”

He demonstrates how the consequences of that campaign continue to reverberate today since “Christian Nationalism as it currently exists is not a form of idolatry or America’s ‘original sin’ but the preservation of a Cold War ideology by the institutions of evangelical Christianity.”

While Colorado Springs is home to prominent evangelical ministries like The Navigators, Young Life, and Focus on the Family, it also features a concentration of U.S. military installations and defense contractors, many of which arrived ahead of the Christian organizations. The result was a constant interaction between the two that reinforced a common set of values and a shared vision for what the country should be. The city was a place where there was little tension between serving God and country.

Yet, that doesn’t mean conflict was absent. In a chapter focused on the religious life of the U.S. Air Force Academy, Shultz portrays an institution that quietly wrestled with religious difference as it was built, specifically in the design and function of the famous Cadet Chapel, and later had to more publicly confront campus controversies over evangelization and sexual assaults. These were problems raised by outsiders or they reflected breakdowns in culture. It wasn’t that the model was fundamentally wrong, but that it wasn’t properly appreciated by those who weren’t part of it or adhered to by those participating in it.

Inside the Protestant chapel at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. (Anthony Quintano/Creative Commons)

Another way to understand this mix of religious and social power is how the agenda of leaders in one place could impact an entire country. This is seen in the wave of anti-LGBTQ laws and measures that have been considered around the country in recent decades. The book documents how Colorado Springs was the hub for those devising the early legal and political strategies to counter national trends and laws they perceived as threatening their cultural ideals.

For those who have lived through the period covered by Jesus Springs, the gift of the book is the contextualization it provides. There’s a connecting of dots that makes the history one has lived more understandable. Yet, such a reader can’t help but consider how much has changed: The institutionalized form of evangelical Christianity no longer enjoys the same power and prominence in society. Christian Nationalism has both intensified and become more suspect. The social agenda of conservative Christians is embraced by fewer and fewer people.

Where does that leave Colorado Springs and what it has represented?

Noting the rise of a more partisan and practically-motivated evangelical movement that’s been eager to compromise ideological purity for political gain, Schultz postulates that Colorado Springs has been left behind by this shift in tactics and direction:

A new strategy requires new institutions and calls forth new leaders. The parachurch ministries that made Colorado Springs into ‘Jesus Springs’ are certainly not irrelevant to American evangelicalism … but they belong to another era, an era of uncontested American power, cultural conservatism, and religious dominance. That age is over, and so too is that stage in the history of evangelicalism. We now live in an era of democratic backsliding, cultural progressivism, and widespread secularization. This era will produce its own version of American Christianity. What that will look like remains to be seen.

Where that will be located is also to be determined, but this book makes the case that the influence of Colorado Springs will linger for a very long time.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood

By the way, Dr. Schutlz has agreed to send a signed copy of Jesus Springs to one paid reader of A Public Witness, so upgrade your subscription today to make sure you’re eligible for that drawing.