NOTE: This piece was originally published at our Substack newsletter A Public Witness.

Experiencing a crisis of faith from encountering the teachings of modern science is a rite of passage for many Christians. The simplistic beliefs taught in too many churches and our society’s lack of scientific literacy can result in a rude awakening when the core ideas of biology, physics, and other fields are first encountered, as they challenge conventional assumptions about our origins and our existence.

My own dark night of the scientific soul came in college. If evolution was truly an unguided process with no ultimate end, then the implications were scary: life was essentially without purpose and the reality of God was a foolish fantasy.

Friends told me not to worry. They assured me that scientists were questioning and contesting such claims. They encouraged me to read Michael Behe’s Darwin’s Black Box. They pointed me to others promoting “Intelligent Design” — a movement claiming the world bore evidence of complexity and intentionality, which made the hands of a designer a more obvious explanation for our beginnings and current state than evolution and natural selection.

What I could not have recognized then, but is clear in retrospect, is that my working through these issues with fear and trembling as a college student paralleled a larger cultural moment. There was a friction felt between faith and science that church, academy, and society were all navigating. We were wrestling with what qualifies as scientific truth and how it can be known. The consequences of that debate continue to linger with us in surprising ways today.

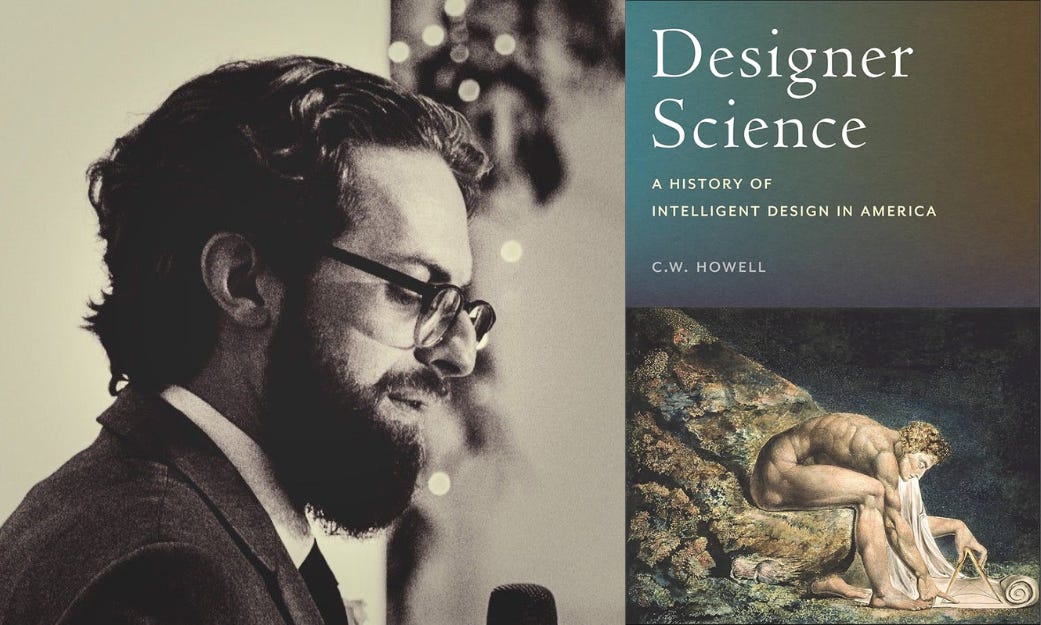

That’s the argument made by C.W. Howell in his book, Designer Science: A History of Intelligent Design in America. Neither a sympathetic defense nor a polemical critique, it documents what transpired, unpacks the broader meaning, and illuminates the effects of this movement that sought to shake the foundations of the scientific establishment.

Howell’s historical narrative contains at least 4 specific subplots:

First, intelligent design both arose within and departed from earlier creationist movements that aimed at undermining evolution, especially in public schools and academic settings. Recognizing the negative cultural stereotypes and legal baggage of those failed attempts, its proponents presented their efforts as motivated by science and disconnected from religious beliefs in order to create distance from their forebearers.

As a result of this approach, many creationists critiqued and rejected the movement’s claims and approach because it refused to adhere to specific theological doctrines around the age of the earth, the descent of all humans from a literal Adam and Eve, and other ideas derived from their biblical interpretations. Still, ID’s critics emphasized its lineage and sympathies with creationism for their own ideological and strategic reasons. Whatever ID may have claimed to be, at its core these opponents saw creationist fingerprints.

Second, ID theorists perceived the debate about human origins as fundamentally not about science or religion, but philosophy and metaphysics. ID’s main argument was that evolutionary thinking in its strongest form is naturalistic. It assumes there is nothing beyond the material and there can be no supernatural force that acts within the world. Thus, everything that exists must have a natural cause. Science is the quest to find and understand those causes. ID argued that this perspective was too limited. By presupposing a materialistic world, scientists missed any evidence for — and ruled out the possibility of — non-naturalistic causes.

Third, this cultural controversy spilled over into the political and legal realms. Howell describes in depth the political forces that championed anti-evolutionary ideas to advance non-scientific agendas related to economic and social order. He also rivetingly depicts the legal machinations that ultimately set back the ID movement, perhaps irreversibly.

Fourth, the book suggests a common thread between anti-evolutionary crusaders and skepticism towards climate change, vaccines, and public health measures taken during the COVID-19 pandemic. The perceived bias within and rejection from the scientific establishment towards ID and its creationist precursors bred suspicion of other authoritative findings and guidance offered by those same elites. For a subset of the American public, especially fundamentalist Christians, if science can’t be trusted with respect to human origins, then it is to be doubted on other significant topics as well. Howell highlights how a substantial number of ID leaders participated in and fueled this distrust, along with noting how this undermining may be the movement’s most lasting impact on science.

By now, you may have noted my use of the past tense and writing as if the ID movement is dead. That’s by design, as Howell notes declining activity and public interest in its efforts. Only time will tell if this movement is dying or evolving. Regardless, the gift of Designer Science is its dispassionate and incisive historical examination of a complicated cultural phenomenon. It also highlights other voices, like theistic evolutionists, that sought to be heard amidst the shouting match between ID’s advocates and Darwin’s materialist defenders.

Most Christians I know want to see science and religion as mutually revealing of God’s handiwork (granted, I don’t run in creationist circles). They don’t believe the world can only be explained by natural causes, but they hold profound appreciation for the rigor and findings of the scientific community. Indeed, my way out of that spiritual crisis was reading the Catholic biologist Kenneth Miller’s book, Finding Darwin’s God. The subtitle captures the spirit of its argument: A Scientist’s Search for Common Ground Between God and Evolution.

Dr. Howell has agreed to send a signed copy of Designer Science to one lucky paid subscriber of A Public Witness. Make sure to upgrade your subscription right away so you can be eligible for that drawing.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood